More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

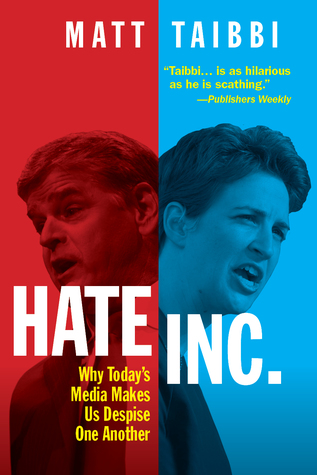

Matt Taibbi

Read between

October 31, 2019 - March 2, 2020

Ironically, the kind of open devotion Thompson made famous in Campaign Trail: ’72—when he pined for George McGovern and crisscrossed the country arguing for his election to the White House, like Kafka’s Land Surveyor searching for redemption in the corridors of The Castle—has now become standard in both “left” and “right” media.

The difference is Thompson was pining for a poetic idealist vision of a better world that (as it turned out) never had a chance of becoming reality.

My personal religion is neither right nor left but absurdist. I think the world is basically ridiculous and terrible, but also beautiful. We try our best, or sometimes we don’t, but either way, we typically fail in the end.

Humanity to me is the Three Stooges, and gets funnier the more it attempts to deny it.

I began a few years ago to be conscious of the business drifting toward something truly villainous.

When you go looking for something specific, your chances of finding it are very bad. Because of all the things in the world, you’re only looking for one of them. When you go looking for anything at all, your chances of finding it are very good.

The book’s central idea was that censorship in the United States was not overt, but covert. The stage-managing of public opinion was “normally not accomplished by crude intervention” but by the keeping of “dissent and inconvenient information” outside permitted mental parameters: “within bounds and at the margins.”

Manufacturing Consent explains that the debate you’re watching is choreographed. The range of argument has been artificially narrowed long before you get to hear it.

As I would later discover in my own career, there are a lot of C-minus brains in the journalism business. A kind of groupthink is developed that permeates the upper levels of media organizations, and they send unconscious signals down the ranks.

A propaganda system will consistently portray people abused in enemy states as worthy victims, whereas those treated with equal or greater severity by its own government or clients will be unworthy.

The uglier truth, that we committed genocide on a fairly massive scale across Indochina—ultimately killing at least a million innocent civilians by air in three countries—is pre-excluded from the history of that period.

We also volunteered to reduce or play down stories about torture (“enhanced interrogation”), kidnapping (“rendition”), or assassination (“lethal action,” or the “distribution matrix”).

The relentless now now now grind of the twenty-four-hour cycle created in consumers a new kind of anxiety and addictive dependency, a need to know what was happening not just once or twice a day but every minute.

The rest of the news? As one TV producer put it to me in the nineties, “The entire effect we’re after is, ‘Isn’t that weird?’”

We sold anger, and we did it mainly by feeding audiences what they wanted to hear. Mostly, this involved cranking out stories about people our viewers loved to hate.

Selling siloed anger was a more sophisticated take on the WWE programming pioneered in Hannity & Colmes. The modern news consumer tuned into news that confirmed his or her prejudices about whatever or whoever the villain of the day happened to be: foreigners, minorities, terrorists, the Clintons, Republicans, even corporations.

The system was ingeniously designed so that the news dropped down the respective silos didn’t interfere with the occasional need to “manufacture” the consent of the whole population. If we needed to, we could still herd the whole country into the pen again and get them backing the flag, as was the case with the Iraq War effort.

People need to start understanding the news not as “the news,” but as just such an individualized consumer experience—anger just for you.

As it turns out, there is a utility in keeping us divided. As people, the more separate we are, the more politically impotent we become.

This is the second stage of the mass media deception originally described in Manufacturing Consent. First, we’re taught to stay within certain bounds, intellectually. Then, we’re all herded into separate demographic pens, located along different patches of real estate on the spectrum of permissible thought. Once safely captured, we’re trained to consume the news the way sports fans do. We root for our team, and hate all the rest.

Fake controversies of increasing absurdity have been deployed over and over to keep our audiences from seeing larger problems. We manufactured fake dissent, to prevent real dissent.

Why do they hate us? We in the press always screw up this question. Many of the biggest journalistic fiascoes in recent history involved failed attempts at introspection. Whether on behalf of the country or ourselves, when we look in the mirror, we inevitably report back things that aren’t there.

Under the new formulation, One Million Hours of Trump became One Million Hours of Trump (is bad!). Conveniently for our sales reps, the new dictum centered around the idea that we not only should not reduce the volume of TrumpMania, but rather we must, if anything, increase it, because we now had an enhanced “responsibility” to “call him out.”

One additional bizarre Trump-inspired change to reporting that took place in 2016 involved polls: we increasingly ignored data favorable to Trump and pushed surveys suggesting a Clinton landslide.

In the same way, conventional wisdom after the 2016 vote steered attention away from the generation of press practices that had degraded the presidential campaign process to the point where the election of someone like Trump could even be possible.

The same pundit class that had raised us on moronic messaging, like Newsweek’s “Fighting the Wimp Factor” cover of George H. W. Bush, created a new legend about how the Trump-era press corps had learned its lesson, and would be returning to its more natural role as serious-minded opponents of dumb populism.

For example, we weren’t going to screw around with words like “misstatement” anymore. The new Press Corps 2.0 would put the word “lie” in headlines. Go ahead and see if we wouldn’t. We were tough now.

Eventually there was a great collective patting of backs when most of the major papers and networks decided to approve the forbidden word.

Sanders spoke of the divide between the public and elite institutions, of which the press was now clearly considered one. “It’s not just the weakness of the Democratic Party and their dependency on the upper middle class, the wealthy, and living in a bubble,” he said. “It is a media where people turn on the television, they do not see a reflection of their lives. When they do, it is a caricature. Some idiot.”

By 2012 I had a theory of the presidential campaign as a complex commercial process. On the plane, two businesses were going on in tandem. The candidates were raising money, which mostly entailed taking cash from big companies in exchange for policy promises. In the back, reporters were gunning for hits and ratings.

After 2012 I believed any candidate smart enough to run against all this insanity would do well. In early 2016, when I saw that Trump was doing exactly this, I had a flash of insight that he was going to be president. In the first feature I wrote about Trump, I talked about how he was looking “unstoppable,” and explained: It turns out we let our electoral process devolve into something so fake and dysfunctional that any half-bright con man with the stones to try it could walk right through the front door and tear it to shreds on the first go.

Two data points stood out after 2016. One involved those polls that showed confidence in the media dipping to all-time lows. The other involved unprecedented ratings. People believed us less, but watched us more.

It boggles my mind that people think they’re practicing real political advocacy by watching major corporate TV, be it Fox or MSNBC or CNN.

By 2016 we’d raised a generation of viewers who had no conception of politics as an activity that might or should involve compromise.

Your team either won or lost, and you felt devastated or vindicated accordingly. We were training rooters instead of readers. Since our own politicians are typically very disappointing, we particularly root for the other side to lose.

People who watch MSNBC, meanwhile, are tuning in to receive mega-doses of the world’s thinnest compliment, i.e. that they’re morally superior to Donald Trump.

Images of poor, inarticulate people are disturbing to audiences, especially upscale ones (read: people with disposable incomes who can respond to advertising). That’s why we don’t show poverty on TV unless we’re laughing at it (Honey Boo Boo) or chasing it in squad cars (Cops).

The same kinds of reporting techniques increasingly dominate anti-Trump media, however. The constant drumbeat of “It’s the beginning of the end” stories about “bombshells” causing the “walls” to “close in” on Trump—so comic that a mash-up of such comments dating to Trump’s first week in office has gone viral—is a case of straight-up emotional grifting.

Editors know Democratic audiences are devastated by the fact of the Trump presidency, so they constantly hint at any hope that he’ll be dragged away in handcuffs at any moment. This is despite the fact that reporters know the legal avenues for removal are extraordinarily unlikely. Such puffing of false hopes is the most emotionally predatory behavior that exists in journalism.

Even worse has been Russiagate, which became a serious problem throughout the business for a variety of reasons, among them the fact that it delayed the necessary journalistic process of examining what really happened in 2016. On top of that it’s also been a clear case of moral-panic journalism.

The only constant will be more and more authoritarian solutions. In the social media age, we can scare you as never before.