More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

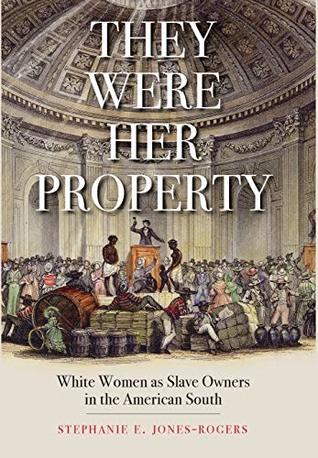

In They Were Her Property I build upon these earlier studies, but I also depart from them in significant ways. I focus specifically on women who owned enslaved people in their own right and, in particular, on the experiences of married slave-owning women. In addition, I understand these women’s fundamental relationship to slavery as a relation of property, a relation that was, above all, economic at its foundation. I am not suggesting that this was these women’s only relationship to the institution or that the economic dimension of their relations overrode other aspects of their connections to

...more

By definition and in fact, the mistress was the master’s equivalent. Thus, when South Carolina legislators declared that “every master, mistress or overseer, shall and may have liberty to whip any strange negro or other slave coming to his or their plantation with a ticket” (the pass an enslaved person had to carry when he or she left the master’s estate), they were not imbuing mistresses with subordinate powers or power in their husbands’ stead; they were recognizing the comparable powers and authority that these women possessed.20

which abolition eventually put an end. When FWP employees traveled through the South searching out glimpses of the past through their interviews with formerly enslaved African Americans, individuals like Litt Young discussed and identified their female owners. Serving as the metaphorical flies on the walls of southern households, formerly enslaved people talked about some of the most violent, traumatic, and intimate dimensions of life for those who were bound and those who were free. They heard and saw things that typically remained obscured from view, details that white slave-owning couples

...more

Additionally, although some formerly enslaved people were young when they were freed, it is unlikely that they could forget what psychologists and gerontologists call “salient life events”: pivotal experiences such as marriages, births, deaths, and, in the context of slavery, brutal beatings, sexual assaults, or familial separations that occurred after the sale or relocation of loved ones. Delicia Patterson, for example, was fifteen when her owner brought her “to the courthouse,” and “put [her] up on the auction block to be sold.” When Anne Maddox was thirteen, she was part of a speculator’s

...more

30 To be sure, formerly enslaved people often responded to questions about their enslavement with silence because they did not always want to remember or talk about their experiences. But thousands chose to do so despite their reservations. They told their stories in an atmosphere of intense racial hostility and in a region where simply refusing to step off the sidewalk when a white person passed by could result in their deaths. They believed that telling their stories was worth these risks. I honor their courage, heed their words, and foreground their testimony and remembrances in this book.

Slave-owning women rarely talked about their economic investments in slavery, and they wrote about them even less. Their silence did not reflect their aversion to slavery or human trafficking. Many of them simply did not have the time or the skill to put their thoughts on paper, while those who did probably saw their pecuniary investments in slavery as commonplace and unworthy of note. This is their story.

No group spoke about these women’s investments in slavery more often, or more powerfully, than the enslaved people subjected to their ownership and control. They were the people whose lives were forever changed when a mistress sold someone just so she could buy a new dress. They were best equipped to describe the agony that shook their bodies and souls when they returned from their errands to discover that their children were gone and their mistresses were counting piles of money they had received from the slave traders who bought them. Only enslaved people could speak about their female

...more

Slave owners occasionally gave their female family members human property in ritualized affairs that helped mold their young daughters’ development as slave owners from early on. The elders would join the hands of young heiresses together with those of the slaves they were receiving and tell them that the enslaved people in question were their property forever.11

The objective in requiring such deference was simple. Slave owners wanted enslaved people to recognize the power that white children possessed over them, even at the time of their birth. George Womble asserted that his owner wanted the slaves he owned to hold “him and his family in awe”; he compelled them to “go and pay their respects to the newly born white children on the day after their birth. They were required to get in line, and one by one, they went through the room and bowed their heads as they passed the bed and uttered ‘Young Marster,’ or if the baby was a girl they said: ‘Young

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

This young white girl and the enslaved woman who had cared for her learned at least two important lessons that day. They came to understand that there was no inherent chasm between violence and ladyhood in everyday life, even in the eyes of white patriarchs. They also learned that the intimacies that might have been forged between them over the years made no difference to the power that their society accorded to this young white girl over her racial “inferiors.” In fact, it was that power that made such cross-racial intimacies possible in the first place.

In 1835, the abolitionist Catharine Sedgwick wrote a three-volume novel, set during the American Revolution, whose protagonists were the Linwoods, a slaveholding New England family. They owned a woman named Rose who was very close to her owner’s daughter, Isabella. One day, Isabella asked Rose if she was happy, and Rose replied that she was not because she was a slave. Isabella recounted her parents’ kindness toward Rose and remarked how much she and her brother loved her. Rose replied that slavery was a “yoke, and it gall[ed]” her that she could be “bought and sold like cattle”; she would

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

It is important to note that young white southerners, by virtue of their skin color, were empowered by law and custom to exercise control over any enslaved person they crossed paths with, even those they did not own. The landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted published an account of his travels throughout the region that included an encounter he had with a southern girl and an elderly enslaved man: I have seen a girl, twelve years old in a district where, in ten miles, the slave population was fifty to one of the free, stop an old man on the public road, demand to know where he was going,

...more

These affairs also underscored the economic relationship between slaves and young white women’s coming of age because white parents often sold enslaved people in order to help finance their daughters’ weddings. Ben Johnson’s master, for example, sold Ben’s brother Jim in order to pay for his daughter’s wedding dress.58 Transactions such as these served as a brutal lesson for the other enslaved people in Ben Johnson’s community, and an equally important one for the new bride: she could always sell one of her slaves, separating him or her from everything and everyone he or she knew and loved, if

...more

sole and separate use.63 While parents presented their daughters with both enslaved males and females as inheritances upon marriage, they more frequently gave them female slaves. From a logical perspective, their decision to do so might seem motivated by the rationale that enslaved women and girls would be more useful to daughters, who bore the bulk of the domestic responsibilities in and management of their households, and sometimes this was the case. But they also gave enslaved girls and women (especially those of childbearing age) to their daughters, because females possessed the

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

But over the long term, enslaved women, because of the children they would potentially produce over the course of their lives, were far more valuable. If slave owners were patient, “producing children was a cheap alternative to purchasing them at the market.”69 Henrietta Butler’s mistress Emily Haidee clearly knew the value that enslaved women possessed, and she developed two long-term financial strategies to maximize their worth. She not only forced Butler’s mother to engage in nonconsensual sex with enslaved men so she could “have babies all de time,” she made Butler do the same. When the

...more

One formerly enslaved woman remembered overhearing her mistress tell a prospective buyer that she “wouldn’t sell her for nothing” and “wouldn’t take two thousand for her” because she was her “little breeder.”76 In another community, a white traveler named Eli West remembered one enslaved woman who simply could not, or would not, conceive. After she continually failed to become pregnant, her mistress had her stripped naked and whipped her severely. When this brutality proved ineffectual in remedying the problem, her mistress sold the woman to slave traders.77

White slave-owning women further underscored their investments in the children enslaved women bore when they made efforts to provide for their nutritional and physical needs. While such actions might seem benevolent or “maternalistic,” the economic advantages of caring for the children they enslaved often motivated these women’s choices, and frequently these mistresses had their eyes on the slave market. Sallie Paul reasoned that slave owners in her community fed enslaved children well in large part because they wanted to “make dem hurry en grow cause dey would want to hurry en increase dey

...more

Scholars of jurisprudence define ownership as a “bundle of rights” that an individual has to a thing. According to A. M. Honoré, that bundle includes “the right to possess, the right to use,” the right to be secure in one’s property, “the right to manage (which involves ‘the right to decide how and by whom the thing owned shall be used’), the right to the income of a thing (which includes the ‘fruits, rents, and profits’) . . . the right to alienate the thing . . . during life or on death, by way of sale, mortgage, gift or other mode . . . and the liberty to consume, waste or destroy the whole

...more

Enslaved and formerly enslaved people recalled the ways their female owners exercised authority over them. They made it clear that white women did not subordinate their authority to white men nor did they confine themselves to operating at the “mid-levels of power,” in Foster’s phrase.12 Their status as slave owners granted them access to a community that was predicated upon the ownership of human beings and afforded them rights they did not possess in other realms of their lives. White women embraced their role within this community, assumed positions of power over slaves within and outside

...more

South. Laws dating back to the colonial period routinely recognized that mistresses owned enslaved people in their own right, and these same laws acknowledged the fact that these women were capable of exercising mastery over the enslaved people they owned.14 In fact, southern laws held the mistresses accountable for their slaves’ misconduct. For example, when an enslaved person in Louisiana was found “guilty of revolting, or of a plot to revolt against his or her . . . mistress . . . or of willfully and maliciously striking his or her . . . mistress, or the child or children of his or her

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

The “management of negroes” advice columns that appeared in agricultural journals such as DeBow’s Review and the Southern Planter suggest that many southern white men coveted the role of slave master and yearned to rule over enslaved people, even those who were not their own. But this was not always the case. Rosalie Calvert found that her husband had no interest in being a master, and she had to assume the role herself. In 1818 and 1819, Calvert wrote several letters to her sister Isabelle complaining about her husband’s laziness and indifference to all matters related to plantation

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

time. Mistresses also sought to establish the parameters of proper conduct for men whom the state empowered to punish their slaves. A woman named Mrs. Harris, for example, hired out an enslaved boy she owned to various men in her community. On one occasion, the boy clashed with the man who had hired him, and during their altercation the boy “knocked” his employer in the head. The injured man summoned the community squire and constable, the two men stripped the boy, and the squire whipped him. The boy began to make so much noise that Mrs. Harris heard him, “came out and told the squire to turn

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

The similarities between men and women’s systems of management become clearer through the testimony of formerly enslaved people. According to Henry Watson, his “mistress had been brought up in Louisiana, and had witnessed punishment all her life, and had become hardened to it.” He had seen her “perpetrate some of the most cruel acts that a human being could, yet I never saw her in a passion when she was inflicting punishment.” Cecelia Chappel recalled that her mistress would give her slaves “sum wuk ter do, so she would kind ob git ober her mad spell ’fore she whup’d us.” This was not feminine

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

But beyond their aversion to blood-stained clothing, slave-owning men tried to distance themselves from the violence of slavery in order to maintain a particular esteem among enslaved people. A slave-owning man from Georgia declared, “I rarely punish myself but make a driver”—typically an enslaved man who assumed the responsibilities of an overseer—“virtually an executive officer to inflict punishment [so] that I may remove from the mind of the servant who commits a fault the unfavorable impression too apt to be indulged in, that it is for pleasure rather than for the purpose of enforcing

...more

Sometimes slave-owning women had good reason to delegate slave punishment to others, and their decision to do so aligned with the choices slave-owning men made in this regard. The white men in their families or those they hired generally proved to be willing participants. Yet slave-owning women also knew firsthand that slave management and discipline could pose difficulties that neither a master nor a mistress was capable of handling. Violent and resistant enslaved people might need more than the authority of a single man to keep them in line.31 Pauline Howell’s enslaved aunt, for example,

...more

the slave market. Most commonly, when formerly enslaved people described households in which double mastery prevailed, they remarked upon a clear differentiation between the broader systems of management and discipline their masters and mistresses used, and frequently they reported that one of their owners would beat them while the other did not. While assumptions based on gender might suggest that women were the ones who refrained from beatings, this was not always the case. Husbands frequently disagreed with their wives’ chosen disciplinary strategies because they were too brutal, and they

...more

When King’s mistress discovered her husband’s plan, she prevented the sale and swiftly retaliated. As King and his master were forced to stand and watch, the mistress commanded the overseer to strip, bind, and whip his mother. The beating “left her laying, all a shiver, on the ground, like a wounded animal dying from the chase.” King remembered his mistress walking away “laughing, while his Mammy screamed and groaned.” His master had a remarkably different response; he stood there “looking sad and wretched, like he could feel the blows.” One woman’s violence toward her slaves was enough to

...more

Most states were in agreement. As long as the punishment did not maim, mutilate, or imperil the life of an enslaved person, brutality was legal. There were, however, exceptions that allowed whites to kill enslaved people with impunity. South Carolina declared it “lawful for any white person to beat, maim or assault” a black person, and “if such negro or slave cannot otherwise be taken, to kill him, who shall refuse to shew his ticket, or, by running away or resistance, shall endeavor to avoid being apprehended or taken.”47

it. One Missouri man recounted in precise detail how Mann’s wife had brutalized Fanny, and claimed that the day after Mann’s wife had tortured Fanny, she was found dead. Fanny was “silently and quickly buried, but rumor was not so easily stopped. . . . The murdered slave was disinterred, and an inquest held; her back was a mass of jellied muscle; and the coroner brought in a verdict of death by the ‘six pound paddle.’” Mrs. Mann fled the district for a few months, but no action was taken against her.52 By some accounts, white slave owners concealed their most brutalized slaves from observers

...more

The brutality of some slave-owning women, especially when it led to disfigurement or death, might strike us as “irrational destruction” that was counterproductive, in large part because it seemed to be in direct conflict with their financial investment in the people they owned. After all, such violence impaired enslaved people’s ability to work and decreased or obliterated their value in the market.54 But a slave-owning woman’s decisions to abuse, maim, or kill her slaves was simply an “extreme version” of her “right to exclude” others from reaping the benefits of having access to the slaves

...more

or who allowed their slaves too much freedom.59 Finally, legislators did not impose legal constraints upon slave owners’ powers to abuse, punish, and kill their slaves out of concern for enslaved people’s well-being. They did so in order to preserve the interests of relatives who would inherit their estates and would suffer if the property was squandered. If abuse and destruction did not threaten to deprive heirs of their rightful inheritances, courts might acquit a slave owner who killed.60

Some of the cases discussed here might appear to suggest that when slave-owning women brutalized and killed enslaved people, southern judges and jurors exonerated them because of gendered ideas about women or an assumption that a woman’s violence toward enslaved people was somehow different from a man’s. But judges and juries were consistent in their leniency toward slave-owning men and women, and southern laws generally allowed most white southerners, not just women, who killed, dismembered, or maimed enslaved people (even those who did not belong to them) to do so with impunity. Most

...more