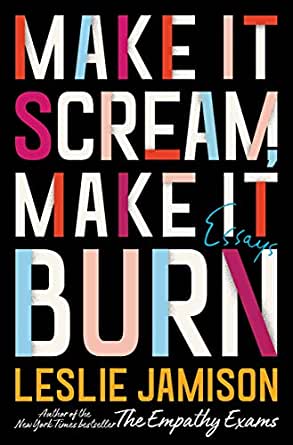

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

But I felt defensive of reincarnation from the start. It wasn’t that I necessarily believed in it. It was more that I’d grown deeply skeptical of skepticism itself. It seemed much easier to poke holes in things—people, programs, systems of belief—than to construct them, stand behind them, or at least take them seriously. That ready-made dismissiveness banished too much mystery and wonder.

I started to believe there was an ethical failure embedded in skepticism itself, the same snobbery that lay beneath the impulse to resist clichés in recovery meetings or wholly dismiss people’s overly neat narratives of their own lives.

Maybe I liked telling myself I was defending underdogs. Or maybe it was cowardice. Maybe I was too scared to push back against the stories people told themselves in order to keep surviving their own lives.

Maybe I wasn’t doing anyone any favors by pretending that my belief system was tolerant enough to hold everything as equally valid. Maybe there were experiences I couldn’t relate to and things I might never believe.

Why did I want to defend these tales of prior lives, anyway? It had less to do with believing I could prove that reincarnation was real and more to do with investigating why it was appealing to believe in it. If we told ourselves stories in order to live, what did we get from stories that allowed us to live again? It was about something more than buffering against the terrifying finality of death. It had to do with recognizing the ways we’re shaped by forces we can’t see or understand.

We tell stories about why we’re lonely, or what we’re haunted by, and these stories about absence can define us as fully as our present realities. Kids build identities around ghosts. A mother believes that her son has trouble making friends because the soul of an old man lives inside him. Stories about past lives help explain this one. They

promise an extraordinary root structure beneath the ordinary soil of our days. They acknowledge that the realities closest to us—the rhythms of our lives, the people we love most—are shaped by forces beyond the edges of our sight. It’s thrilling and terrifying. It’s expansion and surrender at once.

Sometimes I feel I owe a stranger nothing, and then I feel I owe him everything; because he fought and I didn’t, because I dismissed him or misunderstood him, because I forgot, for a moment, that his life—like everyone else’s—holds more than I could ever possibly see.

Does graciousness mean you want to help—or that you don’t, and do it anyway? The definition of grace is that it’s not deserved. It does not require a good night’s sleep to give it, or a flawless record to receive it. It demands no particular backstory.

The more important point is that the impulse to escape our lives is universal, and hardly worth vilifying. Inhabiting any life always involves reckoning with the urge to abandon it—through daydreaming; through storytelling; through the ecstasies of art and music, hard drugs, adultery, a smartphone screen. These forms of “leaving” aren’t the opposite of authentic presence. They are simply one of its symptoms—the way love contains conflict, intimacy contains distance, and faith contains doubt.

You wonder what they feel, people who get married, at the precise moment they commit to their vows. Is it only bliss, or also fear? You hope for fear. Because mostly you can’t imagine feeling anything else. Except when you can summon the edge of a man’s suit against your back, familiar, his hand on your arm, his voice in your ear.

By you, of course, I mean I. I wonder about fear. I don’t want to be afraid.

I wondered if I was falling in love. I wondered if I was built exclusively to fall in love. I worried, sometimes, that I was built more to fall in love than to be in love. But didn’t everyone worry about that? You couldn’t think your way past it. You just had to keep falling in love, over and over again, and hope that it stuck once, to prove it could.

For all her cruelty, the evil stepmother is often the fairy-tale character most defined by imagination and determination, rebelling against the patriarchy with whatever meager tools have been left to her: her magic mirror, her vanity, her pride. She is an artist of cunning and malice, but still—an artist. She isn’t simply acted upon; she acts. She just doesn’t act the way a mother is supposed to. That’s her fuel, and her festering heart.

I punished myself when I lost patience, when I bribed, when I wanted to flee. I punished myself for resenting Lily when she came into our bed, night after night, which wasn’t actually a bed but a futon we pulled out in the living room. Every feeling I had, I wondered: Would a real mother feel this? It wasn’t the certainty that she wouldn’t that was painful, but the uncertainty itself: How could I know?

One of the oldest scripts I’d ever heard about motherhood was that it could turn you into a new version of yourself, but that promise had always seemed too easy to be believed. I’d always believed more fully in another guarantee—that wherever you go, there you are.

I was ashamed of how desperately I wanted to consume. Desire was a way of taking up space, but it was embarrassing to have too much of it—in the same way it had been embarrassing for there to be too much of me, or to want a man who didn’t want me. Yearning for things was slightly less embarrassing if I denied myself access to them, so I grew comfortable in states of longing without satisfaction. I came to prefer hunger

to eating, epic yearning to daily loving.

The female body is always praised for staying within its boundaries, for making even its sanctioned expansion impossible to detect.

I kept trying to explain myself to that doctor, kept trying to purge my shame about the disorder by listing its causes: my loneliness, my depression, my desire for control. All of these reasons were true. None of them was sufficient. This was what I’d say about my drinking years later, and what

I came to believe about human motivations more broadly: we never do anything for just one reason.

The first time I wrote about the disorder, six years after getting help, I thought if I framed it as something selfish and vain and self-indulgent, then I could redeem myself with self-awareness, like saying enough Hail Marys to be forgiven for my sins. I st...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.