More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

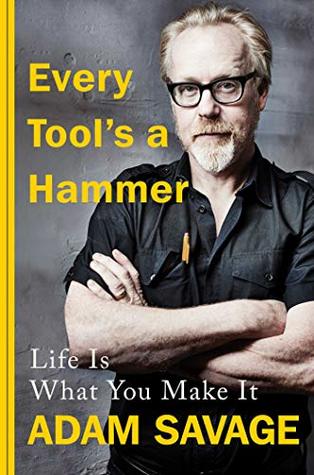

by

Adam Savage

Read between

July 31 - August 18, 2019

Tom has ten primary rules for his shop. He calls them his “Ten Bullets” (he even made a short film about them) and they’re all great, though the one I love the most is Bullet Eight: “Always Be Knolling.” Knolling is an organizational process that Tom learned from, of all people, the janitor at Frank Gehry’s furniture shop in Los Angeles when he worked there in the late 1980s. Every day, the janitor—a fellow named Andrew Cromwell—would come into the shop to sweep and vacuum. But first, before he got to any of that, he would

Part of being the boss of a shop is delegating basic process tasks to your team members so you can focus on the more important, high-level stuff that keeps a shop running:

delegation can be a Herculean task. “One of the things I struggle with is sometimes it’s easier to do something yourself than to train somebody else to think the way that you think about something,” she said. “I don’t want to take the time out of what I’m doing to have to bring somebody else into the fold.”

That is the cruel joke of making, or any creative discipline for that matter: no matter how much you progress in your career, the duality of thrill and terror that exists with all new things will never leave you.

I LOVE DEADLINES! They are the chain saw that prunes decision trees.

as the delivery deadline nears, we should ask that question more frequently, because it helps us remember why we’re there, and what the point of the whole project is.

A deadline shouldn’t feel like a vise slowly crushing your head, it should feel like a sieve through which only the essential elements get pushed by the pressure of time,

Deadlines can help you focus your attention on the elements that are most important to your project’s existence and its purpose, so you don’t become one of those tortured artist clichés who let perfect become the enemy of good.

But for those of us who are generalists or ambitious amateurs making things for ourselves, we can often substitute that knowledge with time. This is the great secret sauce for tackling the unfamiliar.

“No plan survives first contact with implementation.”

That trade-off, of spending time up front to save it on the back end, is one of those choices that becomes clearer with the more experience you get.

A good boss will encourage this type of chutzpah and support a culture that produces more of it. It’s good business sense. As an employer myself now, I appreciate when the people who work with me want to learn more, and express that, and I’m happy to provide the space for them to increase their skill base.

The fact remains that to make something special, to create anything great, it really does take a village. Nobody does anything new truly by themselves. As social beings, we interact.

How does one even begin to captain such a gigantic ship?

“You have to give everyone complete autonomy within a narrow bandwidth,” he replied. What he meant was that after you get their buy-in on the larger vision, you need to strictly define their roles in the fulfillment of that vision, and then you need to set them free to do their thing. You want the people helping you to be energized and involved; you want them contributing their creativity, not just following your orders.

By facing ourselves, I mean watching and learning from our own habits and making changes based on that information to improve ourselves.

Understanding this difference, between what a project should be and what it wants to be, and respecting the gulf between them, is key to fulfilling one’s potential as a maker.

Nothing ever goes exactly according to plan. Facing yourself means taking responsibility for that fact, and making peace with the reality that to build something real and substantive is to give up some measure of control over your preconceptions of what you imagined you were making in the first place.