More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

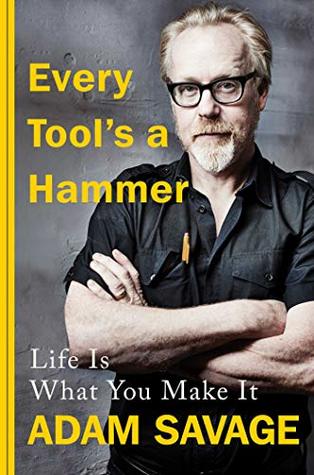

by

Adam Savage

Read between

September 7, 2019 - July 9, 2020

Whenever we’re driven to reach out and create something from nothing, whether it’s something physical like a chair, or more temporal and ethereal, like a poem, we’re contributing something of ourselves to the world. We’re taking our experience and filtering it through our words or our hands, or our voices or our bodies, and we’re putting something in the culture that didn’t exist before.

Putting something in the world that didn’t exist before is the broadest definition of making, which means all of us can be makers. Creators.

nothing we make ever turns out exactly as we imagined; that this is a feature not a bug; and that this is why we do any of it. The trip down any path of creation is not A to B. That would be so boring. Or even A to Z. That’s too predictable. It’s A to way beyond zebra. That’s where the interesting stuff happens. The stuff that confounds our expectations. The stuff that changes us.

When we say we need to teach kids how to “fail,” we aren’t really telling the full truth. What we mean when we say that is simply that creation is iteration and that we need to give ourselves the room to try things that might not work in the pursuit of something that will. Wrong turns are part of every journey. They are, as Kurt Vonnegut was fond of saying, “dancing lessons from God,” and the last thing we want to do is give our kids two left feet.

I see myself as a “permission machine.” In the beginning of his incredible essay “Self-Reliance,” Ralph Waldo Emerson says: “To believe your own thought, to believe that what is true for you in your private heart is true for all men—that is genius.” The essay and in particular that phrase hit me hard in the solar plexus when I first heard it at eighteen years old, and it continues to today. The deepest truths about your experience are universal truths that connect each of us to each other, and to the world around us.

The story genius Andrew Stanton, who cowrote the Toy Story and Monsters, Inc. franchises and directed both Finding Nemo and Finding Dory for Pixar, talked to me about this first pass at listing out the component parts of a project. He was consulting with a group recently, and they were working on the early stages of a project and he said to them: “Can we just all agree right now, this is going to suck? Whatever we’re talking about now, no matter how much we’re getting excited, let’s just all understand it’s going to be a mess.” They were shocked, wondering if he was insulting the project

...more

Mark Frauenfelder, the founding editor in chief of Make: magazine, insists that “you’ve got to do at least six iterations, minimum, of any project before it starts getting good enough to share it with other people.”

TOM SACHS’S TEN BULLETS 1. Work to Code (work within the system) 2. Sacred Space (the studio is sacred) 3. Be on Time 4. Be Thorough 5. I Understand (give/get feedback) 6. Sent Does Not Mean Received (get confirmation) 7. Keep a List 8. Always Be Knolling 9. Sacrifice to Leatherface (take responsibility for mistakes) 10. Persistence

the one I love the most is Bullet Eight: “Always Be Knolling.” Knolling is an organizational process that Tom learned from, of all people, the janitor at Frank Gehry’s furniture shop in Los Angeles when he worked there in the late 1980s. Every day, the janitor—a fellow named Andrew Cromwell—would come into the shop to sweep and vacuum. But first, before he got to any of that, he would go to each workstation and neatly line up all the tools and materials that were still out on the work surface in parallel lines or at 90-degree angles to each other. One day, Tom was still in the shop when Andrew

...more

Here’s how to do it, according to Tom (and, really, common sense): 1. Examine your work space for all items not in use—tools, materials, books, coffee cups, it doesn’t matter what it is. 2. Remove those unused items from your space. When in doubt, leave it on the table. 3. Group all like items—pens with pencils, washers with O-rings, nuts with bolts, etc. 4. Align (parallel) or square (90-degree angle) all objects within each group to each other and then to the surface upon which they sit.

Master craftspeople are confronted with all the same problems and pitfalls as any other maker, they just have the experience (hard won via hardship—nature’s primary learning tool) to see these hazards coming from farther away than the newbie.

Visual cacophony and first-order retrievability are just phrases I came up with to help me communicate what I believe to my collaborators, to my team members in The Cave, and in darker times, to myself. They are not gospel. Your beliefs will be and should be your own. Your answers to the big questions will be different. Maybe, like Nick Offerman, you work best when things flow along the natural continuum of whatever it is that you make. Or maybe, like Jamie, your mind is most creative and your hands are most productive when everything is compartmentalized and in its place. Or maybe you’re

...more

A program called Pepakura can take 3-D drawings and “unfold” them until they’re printable as templates that fit on tiled sheets of standard copy paper. These templates are often used for carving pieces out of EVA foam (like camping mats) but can just as easily be transferred to cardboard, with stunning results. It’s a great way to participate in the ritual of cosplay culture, if you have any interest, as well as to gain invaluable experience with costume design and construction.

“Remember, in every tool, there is a hammer.”I What he meant was that every tool can be used for a purpose for which it wasn’t intended, including the most basic of operations, like hammering.

it wasn’t until I talked to Kevin Kelly, the legendary founding editor of Wired magazine and a tool enthusiast, that I truly understood why, as makers, we should embrace the diversity, and why I, personally, have so many tools. “Freeman Dyson, a famous physicist, suggested that science moves forward by inventing new tools,” Kevin began as we talked on the phone one morning all about tools. “When we invented the telescope, suddenly we had astrophysicists, and astronomy, and we moved forward. The invention of the microscope opened up the small world of biology to us. In a broad sense, science

...more