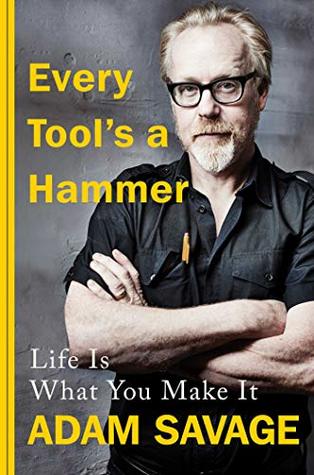

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Adam Savage

Read between

June 22 - October 10, 2022

Whenever we’re driven to reach out and create something from nothing, whether it’s something physical like a chair, or more temporal and ethereal, like a poem, we’re contributing something of ourselves to the world. We’re taking our experience and filtering it through our words or our hands, or our voices or our bodies, and we’re putting something in the culture that didn’t exist before. In fact, we’re not putting what we make into the culture, what we make IS the culture. Putting something in the world that didn’t exist before is the broadest definition of making, which means all of us can be

...more

This is the risk of all creative spirits: every project has as many obstacles as solutions, and with each one there is the chance that one might not end up satisfied with the results; or that others might not be satisfied with them, either, and can’t wait to tell you about it.

that nothing we make ever turns out exactly as we imagined; that this is a feature not a bug; and that this is why we do any of it. The trip down any path of creation is not A to B. That would be so boring. Or even A to Z. That’s too predictable. It’s A to way beyond zebra. That’s where the interesting stuff happens. The stuff that confounds our expectations. The stuff that changes us.

When we say we need to teach kids how to “fail,” we aren’t really telling the full truth. What we mean when we say that is simply that creation is iteration and that we need to give ourselves the room to try things that might not work in the pursuit of something that will. Wrong turns are part of every journey. They are, as Kurt Vonnegut was fond of saying, “dancing lessons from God,” and the last thing we want to do is give our kids two left feet.

the first law of thermodynamics: an object at rest tends to stay at rest unless acted upon by an outside force. Which is to say, to get started you need to become the outside force that starts the (mental and physical) ball rolling, which overcomes the inertia of inaction and indecision, and begins the development of real creative momentum.

Obsession is the gravity of making. It moves things, it binds them together, and gives them structure. Passion (the good side of obsession) can create great things (like ideas), but if it becomes too singular a fixation (the bad side of obsession), it can be a destructive force.

In my experience, when you follow that secret thrill, ideas pop out from the woodwork and shake out of the trees as the gravity of your interest pulls you farther down the rabbit hole.

There is a belief among many of these types, that to jump with both feet into something like that is to play hooky from the tangible, important details of life. But I would argue—and have—that these pursuits are the important parts of life. They are so much more than hobbies. They are passions. They have purpose. And I have learned to pay genuine respect to putting our energy in places like that, places that can serve us, and give us joy.

“To believe your own thought, to believe that what is true for you in your private heart is true for all men—that is genius.”

But what does that mean, to go deep? As a maker, it means interrogating your interest in something and deconstructing the thrill it gives you. It means understanding why this thing that has captured your attention has not let go, and what about it keeps bringing you back. It means giving yourself over to your obsession. I

I think Kubrick wants us to understand that the tragedy of war is that it’s often envisioned by idiots and executed by professionals.

For a twelve-year-old, seeing people curse on TV was way more of a revelation than the prospect of atomic annihilation.

When your project feels like a lion that needs to be tamed, a comprehensive checklist can be both the whip and the chair.

I find making lists to be one of the greatest stress reducers besides meditation.

It’s one of the ways I manage the stress of a project. Get the hard stuff out of the way first, then the specter of all those empty checkboxes becomes less intimidating because the tasks get successively easier and the checkboxes get filled in just as quickly.

Every day, there are going to be problems that seem to solve themselves and problems that kick you down the stairs and take your lunch money.

Here’s how to do it, according to Tom (and, really, common sense): 1. Examine your work space for all items not in use—tools, materials, books, coffee cups, it doesn’t matter what it is. 2. Remove those unused items from your space. When in doubt, leave it on the table. 3. Group all like items—pens with pencils, washers with O-rings, nuts with bolts, etc. 4. Align (parallel) or square (90-degree angle) all objects within each group to each other and then to the surface upon which they sit.

There is no skill in the world, I have since discovered, at which you get better the less sleep you have.

My big problem is that I want to do too many things, and if I load them all up on my plate because I know, individually, I can complete each task more quickly than anyone else, the end result is that nothing gets done and, thanks to my chronic impatience, I haven’t helped my younger collaborators learn new skills to make them better.

I’m naturally allergic to telling people things they don’t want to hear, but by looking at my own past, I saw how necessary it is to give proper, contextual feedback to the people you work with—to acknowledge their work, to appreciate their effort, and to correct their mistakes.

In order to meet the delivery demands for Discovery Channel, we filmed forty-two weeks out of the year, in three-month blocks, with two weeks off in between.

When your project is starting to lag, figure out a date that is as important to you as the project, then work backwards from there. Trust me, you’ll get it done.

It’s not even enough to have all the skills required to make it—knowing that you can build something isn’t the same as knowing how you’re going to build it.

Because of our contrasting styles, the only way we knew how to translate an idea from one of our minds to the other’s was through a process we liked to call . . . arguing.

In all this talk of failure, what we are really talking about is iteration, experimentation.

Your job as a creator is to take as many of the wrong turns as necessary, without giving up hope, until you find the path that leads to your destination.

Every maker needs to give themselves the space to screw up in the pursuit of perfecting a new skill or in learning something they’ve never tried before.

Jamie was pissed, and when Jamie gets pissed, he doesn’t show it much in his voice or his manner, instead his head turns bright red.

If you are struggling to figure out how to move forward in your job or your environment, whether you’re in a creative field or not, my best advice is to figure out any aspect(s) you find interesting, and share that interest with colleagues and bosses in an effort to learn more about it.

Pictures rarely communicate all the necessary information about how skillfully a job was completed.