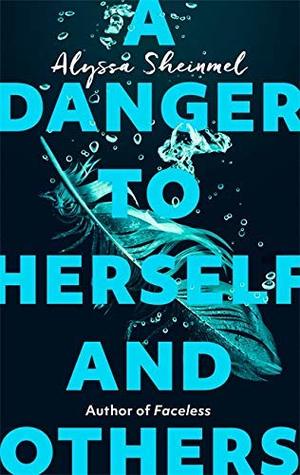

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

It wasn’t my fault. Accidents happen.

Maybe I’ll become a psychologist so I can prove Dr. Lightfoot’s techniques are absurd. Maybe I can get her license revoked for keeping a person like me in a place like this.

The monotony is enough to drive a sane person crazy.

So like I said, he was a good guy.

Okay, I know: He never actually said that he wanted to break up with her.

Didn’t they teach her not to turn her back on her patients in medical school?

“They don’t trust us as far as they can throw us.” “Okay, bad choice of words, but you see what I’m getting at, right?”

(I look up at the ceiling so she won’t see me rolling my eyes again. Her voice goes all earnest and sappy whenever she talks about Joaquin.)

Beside-Me-Annie.

It’s the Schrödinger’s cat of waiting.

if you lock a cat in a box with a radioactive atom, the cat’s survival depends on whether or not the atom decays and emits radiation. So until you open the box and see the state the cat is in, it’s both alive and dead.

“If he loves me, he’ll wait. And if he doesn’t, I’ll find someone else who does.”

Lucy’s breathing is shallow and steady; she’s asleep. The room feels so much warmer with her here.

“I thought Agnes’s boyfriend’s name was Matt.”

Agnes had a boyfriend back home? Another boyfriend?

Now it turns out Agnes wasn’t so good after all.

Not that any of this will ever go to trial. But it’s good to have some new ammunition, just in case.

Lucy doesn’t believe Dr. Lightfoot. She believes me.

I want to ask her if the low dose means she thinks I’m only mildly psychotic, but I don’t. I go on being a good puppy,

Maybe it’s the dead of winter.

Just call a woman a jerk. That’s what you’d call a man.

I pushed her. Not a push, not really. A little tap. Just to see what would happen. I sit up. Did Lucy say that? Those are my thoughts, my memories from the night Agnes fell. We’re getting too old for these games.

“Lucy!” I shout. Now my voice is hoarse. “Lucy!”

Actually, I’m scared of what I won’t see. Who I won’t see.

Why would we have given you a roommate when we said you were a danger to yourself and others?

But then I see something I didn’t notice before. Lucy’s bed, the bed across from mine, the bed I had to step around on my daily walks about the room. It’s gone.

Dr. Lightfoot sighs heavily, standing up. “All right, let’s move her. I don’t want her to hurt herself.”

Lightfoot shakes her head. “I don’t use that word. But you are sick. Your brain works differently than other people’s.”

Sick is her euphemism for crazy; she practically admitted it. They probably taught her to say that in medical school. “Stop trying to trick me.”

Lightfoot said: I’ve suspected this for some time.

It was Lucy’s voice I heard the night Agnes fell, Lucy’s voice saying, just a little tap, before we ever met.

But can you really call it sanity when it isn’t real, it isn’t natural, it’s chemically induced? When it doesn’t technically belong to me because I wouldn’t have it without the pills they keep giving me?

Then I picture them dressed like construction workers, doing heavy lifting and rewiring to get my brain cells into proper working order. I imagine a sedative as a traffic jam keeping the workers from getting to all the right places, from making it to their corner offices in time for their all-important meetings.

There was never a Lucy to argue with. To read a single word with.

To make funny faces behind Lightfoot’s back. Lucy can’t still be here. Lucy never was here to begin with.

I didn’t bring it with me to California because it’s a touch too small, back from when I used to be an A-cup, before I blossomed into an A/B-cup, which isn’t much of a blossoming when you think about it.

That might remind the judge that except for a twist of fate—a strong gust of wind as she fell, a slightly different angle of descent—Agnes’s injuries could have been fatal.

“Agnes Smith’s life will never be the same,” he begins.

It’s October second; summer is over.

are we less our true selves than we were before? Because that means I was myself this summer:

The person I am now won her case, but I’ve never felt more defeated.

I’m not sure whom she’s testing: me (out in the world without institute supervision for the first time in months), or my mom (alone

with her daughter for the first time since her diagnosis).

“I cried all night in Monte Carlo,” I say suddenly. Mom stops walking and turns around.

But my father stays quiet. A daughter with mental illness doesn’t exactly fit into my parents’ lifestyle.

What’s so great about being normal? almost as often as he said I should broaden my horizons.

I don’t think this is the sort of abnormal he had in mind.

I’m tired. I want to go home. Not back to New York, but back to the institution, back to my room with the magnetic lock on the door.

They think I might make a run for it. They think now that I’ve had a taste of freedom, I won’t go back to the institute without a fight.

Maybe I’ll be in some kind of cage forever.