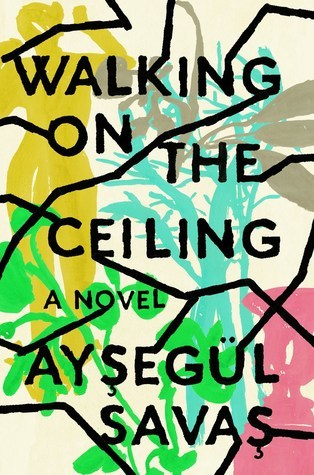

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

I wondered how it was that people knew what to do. Small things, I mean. The rituals of a day. The hours.

The first impression of a city is supposed to be the most authentic—the only time an outsider is allowed to see its essence. Everywhere around me, I saw life sprouting.

From my window, I saw pools of orange light beneath lampposts, circles of leaves on the pavement. The city changed day after day, slipping into a new season, without my taking part.

The coincidences always amazed me even if I knew that they were neither miracles nor revelations but the result of looking at the world deliberately and searching for connections.

“I’ll cross the city unspooling our invisible thread,” he said. “Hold tight to the other end.”

In his love for these peculiar places, he was like an anthropologist, or an accountant. I couldn’t quite tell which, because I was never certain what lay beneath M.’s fascinations. Sometimes I imagined that they were a sign of sorrow, a wish to care for and preserve things on the brink of disappearance. Other times, I thought that they were nothing more than a tedious desire to accumulate.

Now, it surprises me even more that M. and I could surround ourselves with beauty and not pay particular attention to it. I feel that we were always breaking the rules, defying the proper way to do something. Perhaps I only say this because life here in Istanbul now is so deprived of these indulgences.

Even when we don’t have the heart to read the papers, are too worried to consider all the possibilities, and have lost count of all that’s vanished, we continue to talk about Taksim Square. It is the cliché of the changing times. Or perhaps its symbol.

It’s remarkable to me that a foreigner has seen this loneliness in our city. He has seen right through the hills and waters to the very heart of Istanbul. Such a loneliness it robs you of words.

“Nurunisa across the river: Have you dropped our invisible thread?” I had made up my mind that once he asked me directly why I was upset, I would tell him a true story, something simple and direct. This was the condition I had set and I waited impatiently for him to understand, to want to know and admit he cared. I don’t even know what I would have told him if he asked. But the question itself would have assured me that M. was the person I thought I knew.

When my mother told me a story from her past, I would wonder why that version of herself didn’t match the person I knew in life. I accepted that so much had happened before me. And I was always aware of that threshold between the two times. In my mother’s stories, there was always this same silent accusation that I heard when I arrived in Istanbul. Look what happened to me.

I had always liked the feeling that I could board a train and leave the city whenever I wanted. I liked the idea of arriving at a new place, and the brief period of time when my foreignness would be legitimate.

I think that Paris was also changing at that time. Fear and distrust seeped in from every corner. But I did not mind the change so much, or I ignored it. This wasn’t really my city, after all, and change does not pain strangers in the same way.

People will come together and they will separate, but the city, Akif amca writes, will remain. I don’t know whether the thought fills him with hope or sadness.

What mattered most was that memory was stripped of bitterness and retold with joy. And once it took root, it grew bigger, this story of how things had been. It was a voice speaking through us, inexhaustible, it seemed, past resentment and sorrow. Past all that could not be resurrected.