More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

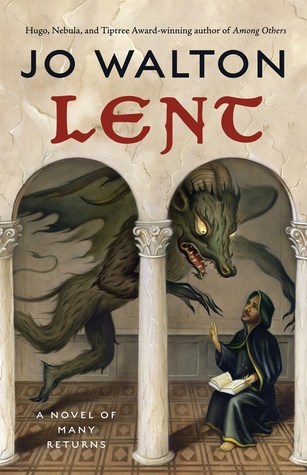

The swinging light and shadows ripple over demon wings, scales, and fur. “I think I can hear something—it sounds like distant laughter. It’s very unsettling. I can see why the nuns might be disturbed.” A demon with stub-wings and a snake’s tail hanging from the eaves pulls open its beak with both hands and roars close by Domenico’s head. His peaceful countenance remains unchanged.

Hysteria among nuns is much more common in the world than demonic incursions. He is only here now because the First Sister was so persistent.

His errors come not from wickedness or ignorance but from moving too fast. And in some cases he is right and the Inquisition was wrong—on apocatastasis, for instance, which doctrine was endorsed by St Gregory of Nyssa.

“Cosimo de’ Medici had himself painted as Saint Cosmas in the most overdecorated cell in the monastery,” Girolamo says. “And if he paid for the monastery, he also put his balls all over it, like a dog spraying every street corner. And for all his famed piety, he said the city can’t be governed by saying Our Father.”

It’s true Lorenzo doesn’t rule with soldiers like the Bentivoglios in Bologna or the Sforza in Milan—except when he hires their soldiers for his wars, the way he did after the Pazzi Conspiracy. He doesn’t rule with laws like Trajan or Solomon, either. He rules with favours and patronage and gold coins—buying a man’s freedom here, giving another work there. Writing ribald songs for Carnival and drinking in the streets with the wool workers. Having a Platonic symposium in his villa with the scholars. Paying for the education of an orphan who will be his man when he grows up. Giving donations to

...more

Yes, Lorenzo looks out for his people, as his father and grandfather did. He rules with a gentle hand. If he wants something in return, all right. If he wants the dedication of my book, or Angelo’s, so that it reflects his glory as well as ours, what harm? He is magnificent. He gives so much to the city. He cares about Florence. The city is his house, and we are his family who live in it.”

A marble faun’s head leers at him from a polished pedestal. It is harder not to flinch from it than it had been before the demons. The demons feared him. This statue fears nothing.

An alabaster bowl of precious stones sits on the bedside table here, and a painted Venus hangs on the wall, but riches do not help, not now. They can do nothing more for Magnificent Lorenzo. He only hopes they have not damned him already.

Two more weeks and it will be Easter. Once Christ is safely risen for another year, he can go home.

we both had dinner with Piero, three days ago. He hadn’t invited either of us for a long time. Did you know he’s instituted hierarchy of seating? At Lorenzo’s table anyone sat anywhere, and you could find yourself between a sculptor’s apprentice and the Ambassador of Venice, and we’d have the most fascinating conversations. But he’s done away with all that.

“I never thought Piero would stoop to poison. It’s such a contemptible ignoble thing to do.

“I think I can forgive him for killing me, though it’s very hard, but not if he has killed Pico,” Angelo says. Girolamo nods. “The Count says he has recovered from his illness.” “I am trying,” Angelo says again. “Christ forgave his torturers. Do you think Piero knew what he was doing, any more than they did?” “If he didn’t then that’s my fault. I was his tutor. I should have taught him right from wrong, or at the very least smart from stupid.” Angelo screws up his face and looks as if he might weep again.

“There are close to thirty thousand men in Florence of the right ages, but only two or three thousand of them could even think of being eligible.” “You can’t expect a wool-dyer or a barber’s apprentice to be competent to run the city!” Capponi protests. Girolamo can’t see why not, if a wool merchant or a master butcher can hold office. He shrugs. “You trust them and even the idle layabouts and thugs when you gather together a great shouting mob outside the Senatorial Palace and call it an assembly,”

“Such a loss, such a marvel,” Benivieni says, behind him. “Truly he was the Phoenix of our age.” It’s true, but he resents Benivieni saying it. Now the Count is dead, Benivieni will spend the rest of his life going around telling people how close they were, how he was his best friend. Girolamo sees it so clearly he isn’t sure whether it’s prophecy or just an observation of human nature.

“Would you tell me the details of the plot?” he asks, carefully. “No. He’s my brother. Besides, there are no details, only the most nebulous dreams. But it would be enough to look like treason, in his letters. It is treason. Piero’s a fool, you know that, I know that, everyone knows it, but he’s my brother still.” The bee settles on a split plum and falls silent.

Pope Alexander Borgia surrendered, and greeted Charles as a brother, which Charles accepted. He took the Pope’s son Cesare off with him, and Cem, the brother of the Ottoman Sultan of Constantinople. Cem died of fever in his camp, but Cesare escaped back to Rome, laughing up his sleeve. Popes should not have sons, and if they do they should not make those sons cardinals, nor should their sons be as terrible as Cesare Borgia. People are saying it is Cesare who is the Antichrist, that he sleeps with his own sister, that he delights in brawling in the streets of Rome.

Then comes a bribe: Girolamo would be made a cardinal if he came to Rome. It is easy to refuse when he knows it means his death, but it means his death either way. If he accepts the bribe, Pope Alexander would know he could be bribed, and was not truly a man of God. If he does not, then the Pope will try harsher measures. He sees quite clearly the choice before him—he can be martyred soon, in Rome, or later, in Florence. He chooses Florence. He refuses the cardinal’s hat, just like his namesake saint, Jerome. Also like Jerome, he writes.

“Borgia’s a terrible Pope,” Valori mutters. “I took a vow of obedience, and I didn’t make a proviso to say I’d be obedient unless the Pope happens to be a Spanish nepotistic simoniac,” he says.

“What is a giraffe?” asks Brother Ambrogio, a young brother from Milan. Everyone falls over themselves to tell him. “It’s a very tall animal from Africa, with a huuuuuge neck,” Domenico says, holding his hands apart to demonstrate. “Yellow, with brown spots, and a bit like a horse,” says Brother Pacifico. “It was very friendly. It would wander around on its own, surprising people by eating herbs from their upper windows,” Brother Tomasso says, laughing to himself. “I remember when it arrived, how surprised we all were! Some people were afraid at first, but we soon came to love it.”

“They say Cardinal Sforza has a parrot that can recite the creed,” Domenico says. Girolamo frowns at him, and Domenico shrinks down in his seat. “We couldn’t get that either, I don’t suppose.” “No. But we need to do something, and not the same things as always,” Girolamo says, crisply, taking control of the meeting. “Carnival is getting out of hand. Last year there was stone throwing and dung throwing and boys and young men extorting money from passersby. Too many people think it gives them license to do whatever they want. And last year the Angels got into fights, and some of them were badly

...more

“In the Piazza in front of the Senatorial Palace?” Girolamo asks, picturing it. “I think that might work. We could get the Angels working on collecting the donations. They’d enjoy that. And it would be more fun than fighting, and more dignified than a greased boar.”

Lorenzo di Credi, a painter and sculptor who is a fervent Wailer, has made a wooden Satan, surrounded by figures of devils, which has been put on top of the whole thing, where it leers down dramatically. “Don’t you mind that being burned?” Girolamo asks him. “We can take it off again before we start the fire.” “No, no. Anything made for Carnival floats was always temporary, and burning will at least give it a good funeral,” Credi says. “It’s a good advertisement for my work. I’m getting plenty of commissions doing what you said in your sermon, Brother Girolamo, more shepherds and fewer kings!”

“But it’s such a waste!” Antonio says. “The books, the paintings, all this cloth!” “It’s a sacrifice to God,” he says. “Five thousand florins,” Antonio says. “No.” “I thought Dominicans cared for learning. How do you know there aren’t valuable unique books being destroyed there?” “Because we do care for learning and I have checked them all,” he says, angry now. “Ten thousand florins.” “No. It’s not for sale.” “What do you care if we look at paintings and statues of naked women far away in Venice?” “You are all God’s children,” he says. The merchant sighs. “I’m robbing my own children, but

...more

“There have been a lot of attacks. The usual thing. Poems pinned up, sermons, open letters against me.” “Saying in terrible Latin that you’re from the swamps of Ferrara, you’re not a true prophet, you want the whole city to live like monks, you have the new French disease of the phallus, and furthermore you don’t understand Aristotle properly,” Silvestro adds. The brothers laugh, or groan. Girolamo is a little hurt by the swipe at his understanding of Aristotle.

“Injustices done in futures that have not yet happened and which will not be done again are easily forgiven,” Marsilio says, smiling and shaking his head.

“Angelo, beds are for sleeping, chairs are for sitting, tables are for piling books.” “All flat surfaces are for piling books,” Angelo says, but he stands up and comes to clear another chair, glancing at the books as he moves them. “Huh, Valla, good, I was looking for that.”

“Who is this Crookback? Do we know any more about him?” Girolamo asks. They all look at Angelo, the only one of them who pays attention to gossip. He grins as he pulls his newly cleared chair closer to the table and sits down. “He’s the head of a company called the White Boars, after the device on their shields. He’s Count of Ravenna and the Duke of Glusta, or some odd name like that. He’s not really what you might call a humanist, but he’s educated, not an enemy of learning. The important thing about him is that he’s the uncle of the King of England.”

Because I can’t go to Rome,” Pico says. “They’ll kill me. They couldn’t possibly condemn you as a heretic, but they can me very, very easily if they want to. The Nine Hundred Theses gives them all the ammunition they could ever want. My synthesis of Plato and Aristotle and the Cabala and the Koran with Christianity isn’t heretical, not really, but it’s very easy for misguided people to see it that way. I was already excommunicated once because of them. It would take very little for that to be revived.”

“You can only torment each other? You really can’t just exchange information?” Pico asks. “No,” Girolamo says, looking at the cups as he pours. “How do you know? Have you tried? Stop fiddling about and look at me!” Shocked, Girolamo spills a little water and mops it with his sleeve. He looks at Pico. “I have tried,” he says. “It’s hard to explain, especially to you. It would be easier to explain it to worse people, strange as that seems. Have you ever known someone who annoys you? Or have you ever known someone for a long time, and fallen into a bad pattern with them so that you’re always

...more

A man who never existed could have whatever relations he wanted.

Then she became really notorious at the siege of Forli of course.” Isabella nods. Everyone has heard the story of how she laughed from the top of the walls at the soldiers who had her children captive and threatened to kill them. She exposed her genitals and said she had the means to make more.

Michelangelo Buonarroti comes over, a cup of wine in his hand. He is growing a beard. “I have it!” he says, delightedly. “What?” Girolamo asks, but Marsilio knows. “That huge block of marble that’s been standing about for so long?” “Yes. I am going to carve the prophet Amos, to go high up on the cathedral. I thought I’d do him with the face of Brother Giovanni. What do you think?”

Crookback never merely walks, he stalks or swaggers or sidles.

“This is what Christ gave Peter. It’s the key to Heaven. I’m not giving it back to a bunch of soft fools like you. What were you planning to do with it anyway?” “Harrow Hell and free the trapped souls,” Girolamo says. It sounds like a ridiculous plan as he says it. “What, free all the demons to ravage Earth? Not such a bad plan as I thought,” he sneers. “But I think it might be better used to renew our old plan of storming Heaven. This is my one and only chance. You’ll never let me have it again. Are you with me Asbiel? You were once. Remember how we wanted to reshape the universe and remake

...more

He slides his arm lower, away from Girolamo’s hurt shoulders and around his waist. “Have you ever copulated, Girolamo?” Girolamo freezes, and knows Angelo can feel that. “I’m—you know what I am!” he says. “I know. I just thought—” “You can’t die with that on your conscience!” “It’s all right if you don’t want to,” Angelo says, and loosens his arm.

Bernardo Bembo, the poet. He might not be in Venice though, he’s an ambassador. His young son is very promising too, Pietro.

“That doesn’t matter. I’ve virginity enough for both of us.”

The two real starting points for this book are Fra Angelico’s Harrowing of Hell and Ficino’s 1498 letter about Savonarola, in which Ficino explains to the Inquisition that Savonarola was a demon but didn’t know. But it was that empty scroll that really started me thinking about him.

The Bonfire of the Vanities is the one thing most people know about Savonarola. It really was more like Burning Man than book burning—a joyful celebration with art set on fire.