More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

“Hell, when I die, bury me the way I came. Want to be ready to show God my scars and ask why.”

They could not see me. I lived my life beside them, beside all of them, and they could not see me. I worked by their side, late into the night, left my shack before the day broke and they still could not see me. Was I the only one who could not tell the difference between a life in bondage and death?

the suggestion that being good meant letting what you loved slip through your fingers to appease a man who questions your humanity. The suggestion that joy meant serving. The suggestion that, though misplaced, he was home. The suggestion that being good meant that he was to protect what was in this oppressor’s interest, but allow his own flesh to meander about life until they were all an infinity of broken men. Strong then, yes. But not a good man. He would not be that.

I walked past the picketed mansions, white and splendid in all of their glory from the road—hiding the stains of ruined lives behind the houses on tall wooden posts.

Their spirits were alive. And most men I knew before, in that place, laid their spirits to rest the first time the cat-o’-nine-tails flew into their backs. And without a spirit, you cannot feel. You react, but the longer you exist in a world without your spirit, the less you feel. And feeling, no matter how low the emotion, is a gift. But in that place we stopped feeling when our spirits were killed. Laughter was a reaction. Tears were a reaction. Those screams were a reaction. But the source of them—the mother of joy, of sadness, or terror—was a ghost like me.

They told us we had no history but darkness, so they kept the books away for fear we might understand the truth better, and thus find those lost selves.

Alike spirits separated at great distances will always be bound to meet, even if only once; kindred souls will always collide; and strings of coincidences are never what they appear to be on the surface, but instead are the mask of God.

No slavers lived under that moon. No more Africans died.

So she hunted it, haunted it through the tiny opening until it rode on my back and crashed into those neglected mud bricks, staining her with its residue.

It had not been a color that he fought, but a spirit. Greed. Perhaps the warriors he fought with in previous weeks had foresight enough to reject this spirit, which extinguishes as much as it enriches, never one without the other. It was greed—that soulless, bottomless thing that killed mothers. Killed would-be lovers. Would not let him be.

Fatigued by her denial of herself, of him, he sat down. He would have wept for her if there had been tears left, for nothing was so tragic as this.

Gerald let her use him. He drowned in the woman he had never met. He bit and tugged at her, drilled into her—let Gbessa do with him all she wanted. Let Gbessa take what was rightfully hers.

There was something suddenly joyous about her, glowing and unafraid. There was something alive in her—her childhood, her curse, her king.

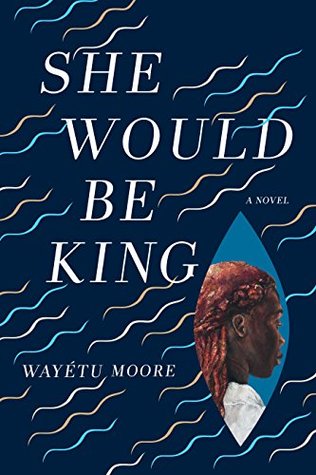

“The girl with the biggest gift of us all. Life. If she was not a girl or if she was not a woman; if she was not a woman or if she was not a witch, she would be king,” I said.