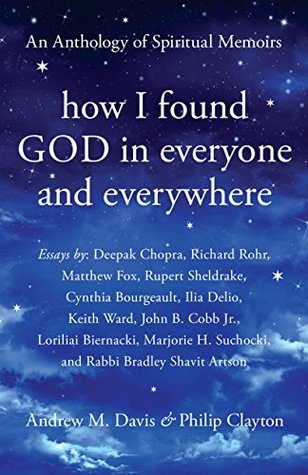

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

August 11 - November 19, 2019

Day is done, gone the sun, From the lake, from the hills, from the sky; All is well, safely rest, God is nigh. Amen, and amen. God was nigh.

From that day onward, I knew that I would devote myself first to the questions as my highest passion.

Only the freedom to challenge orthodoxies can bring transcendence down to earth.

“That of God in Every One.”

The lure is felt in the “fusing-without-loss-of-identity” that we experience in mystical moments and in intimate relationships. Divine action becomes sustenance, nurturing, comfort. The Immanent Divine is the spiritual presence that comes to and into everyone who suffers; indeed, God is that presence that is always already alongside and within.

Martin Heidegger

Holzwege, trails that meander through the forest with no particular destination.

Lichtung, an unexpected opening in the forest where you can s...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Once, when giving a talk, Jane told the amazing story of watching a group of young male chimpanzees walk up a small river they had never visited before. As they came around a sharp corner, they suddenly saw a huge waterfall, crashing majestically into a pond. At first they froze, amazed, taking in what they had just encountered. Then, she said, the young chimps raised their arms above their heads and began to dance with joy. Their response, Jane told the audience, is best understood as awe and wonder.

T.S. Eliot beautifully puts it, “… there is only the unattended / Moment, the moment in and out of time, / The distraction fit, lost in a shaft of sunlight,”

When our eyes are open, we feel wonder; when our souls are open, we feel awe; when our hearts are open, we feel reverence for all that is.

Surely the Divine permeates and sustains all things, closer to us than we are to ourselves, “higher than my highest and more inward than my innermost self” (St. Augustine). And if God is everywhere and in every one, as Julian of Norwich knew, then “all shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well.”

The Rebirth of Nature: The Greening of Science and God (1992).

Science Set Free (2012;

Natural Grace: Dialogues on Science and Spirituality (1996) and The Physics of Angels: Where the Realms of Science and Spirit Meet (also 1996). Matthew’s

Holy Trinity provides an inherently dynamic model of God, and this eternal dynamic process within God underlies the creativity expressed through all nature in the process of cosmic evolution.

have not ceased to be pluralistic about many things. But I believe that at particular junctures in history, humanity faces particular challenges. I am not now pluralistic about whether we should try to save our species from extinction, nor about the relative importance of that task in comparison with most of what goes on in value-free research universities. These are the epitome of the late modernism from which radical empiricism, neo-naturalism, process metaphysics, and, above all, Whiteheadian cosmology rescued me.

Hartshorne occasionally used it in class. In any case, his doctrine of God is emphatically pan-en-theist. For him, what is of central importance is that what we experience, God also experiences. Our joy gives God joy. God shares our sorrows. This gives us the motive to increase joy in the world and diminish unnecessary suffering. He called his ethics, contributionism. If what happens simply ceases and disappears forever after the moment of its occurrence, then meaninglessness threatens. If we know that it contributes to the everlasting life of God, all that happens to us and all that we do

...more

Central to the Abrahamic traditions is divine compassion. Compassion means feeling with. That is the claim that God feels our feelings with us, that we are totally known and understood and accepted. This is affirmed by pan-en-theism, and it is a central part of Hartshorne’s metaphysics.

Whitehead has a strong sense of God as compassionate companion.

I make no claim to certainty, but I rest in assurance.

draw in my breath and begin again. “Yes,” I try to explain to this person, “for sure, if I were claiming that I am God or that God and the world are the same, that would be pantheism. But surely God can inhabit this world of ours, indwell and suffuse it without getting stuck there…” “Oh, you mean you’re a panentheist!”

cosmotheandric, the infinite and the finite continuously interabiding one another, dynamically changing places through a process of continuing self-giving, or kenosis.

“Cosmotheandric” is Panikkar’s neologism of choice to describe this dynamic intercirculation.

Denotatively, it covers much the same turf as panentheism, but connotatively, they are light years apart. Panentheism ties us back into that old static paradigm (this “thing” called the created order is not God, but God can still visit it without getting stuck in it); cosmotheandric (forged from the words cosmos, world; theos, God; and andros, human) speaks implicitly of an intercirculation of realms, of whole different dimensions or planes of being actively infusing each other. It is cosmic, quantum, Einsteinian, portraying the paradox of form and formless more like virtual particles dancing

...more

Jesus is the son of God because we are all sons (and daughters) of God, because that is how a cosmotheandric universe works, because God is not a first cause, not an explanation, but rather meaning itself, throbbing through the entire dynamism, suffusing the attuned heart like the air we breath, like the atoms still reverberating in our bodies from the big bang.

At this point in my thinking, it is not enough for me to proclaim that God is responsible for all this unity. Instead, I want to proclaim that God is the unity—the very energy, the very intelligence, the very elegance and passion that makes it all go.5

Any version of God that is personal, incidental, occasional, fickle, or unknowable cannot be a God I’d call necessary.

I’ve concluded that the point of spirituality is to deliver a kind of medicine to the soul, a recovery program that invests life with “light.”

“On the other hand, this may not be the case at all.”

This presence of God, therefore, is the basis of God’s knowledge: God knows all things relationally.

Because God knows all circumstances affecting any becoming entity, both in terms of its possibilities and its probabilities,

God is an influence toward what good is possible for every...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

God’s power is relative, and is based on ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

on a smaller scale, I like to think that there is a goal of increasing measures of kindness, and that religions and cultures expand insofar

as their communal ideals of kindness toward one another expand to include kindness toward those outside their ordinary circles of care.

God is an incarnational God, whose nature is to reveal Godself for the sake of whatever form of well-being is possible in whatever circumstances.

Kindness, compassion, and a care for the wellbeing of those beyond one’s own ordinary circles of care are the qualities by which doctrine is to be assessed.

my deepest conviction is of the omnipresence of God, and the truest thing we can know about the omnipresent God is the mystery of an all-encompassing love that is beyond reduction to anything else.

The whole universe, in all its beauty, is a suitable icon

through which we acknowledge the presence of a God whose beauty and whose love and whose presence is more than we mortals can ever fully comprehend. And it is enough.

So Trinitarian Christianity gave us a clear pathway out of the problem, by both preserving God’s unknowable apartness (“Father”) and

God’s immanent presence in two different manifestations (“Incarnate Christ” and “Holy Spirit”).

This slowly emerging Trinitarian notion of God was supposed to keep the whole notion of Divinity in dynamic interaction with creation, but by and large it was only the mystics and those who went on inner journeys of prayer who were ever Trinitarian in any practical or pastoral way.

On the immanent-transcendent continuum, clerically-trained theologians felt it was their job to hold down the transcendent end, and protect God’s awesomeness and majesty (much less so among lay and

women mystics, however). Most clergy seem to think that God somehow needs our clerical and liturgical protection, and historically it was always the priestly class whose job it was to hide and protect all sacred objects from the invading barbarians.

In the practical order, I do suspect that most of us first need to experience the “Holy, Holy, Holy” before we can really honor and enjoy that this same transcendent God has also “leapt down from his Almighty throne” (Wisdom 18:15).

most people felt that faith was to stay at that first experienced level of awe, fear, wonder, and transcendence. They felt they had no right to bridge the gap, not yet enjoying the fact that God had already bridged it in the Incarnation, and the generous and universal outpouring of the Spirit (Acts

2:1-13). We always have to allow the initiative from God’s sid...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.