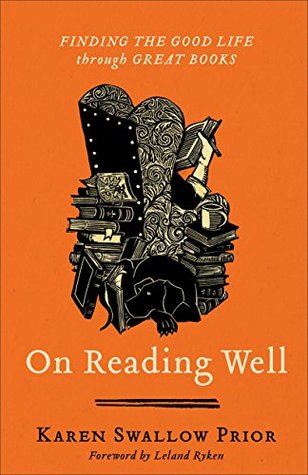

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

April 12 - April 24, 2020

Reading well is, well, simple (if not easy). It just takes time and attention.

Practice makes perfect, but pleasure makes practice more likely, so read something enjoyable.

Read books you enjoy, develop your ability to enjoy challenging reading, read deeply and slowly, and increase your enjoyment of a book by writing words of your own in it.

To read well is not to scour books for lessons on what to think. Rather, to read well is to be formed in how to think.

Reading well adds to our life—not in the way a tool from the hardware store adds to our life, for a tool does us no good once lost or broken, but in the way a friendship adds to our life, altering us forever.

In other words,

plot reveals character. And the act of judging the character of a character shapes the reader’s own character.

Similarly, we can hardly attain human excellence if we don’t have an understanding of human purpose. Human excellence occurs only when we glorify God, which is our true purpose. Absent ultimate purpose, we look for practical outcomes.

Satire points to error, and allegory points to truth, but both require the reader to discern meaning beyond the surface level.

No matter what, adhering to rules is much easier than exercising wisdom.

Virtue requires judgment, and judgment requires prudence. Prudence is wisdom in practice.

“Prudence is the knowledge of things to be sought, and those to be shunned.”

Prudence is “at the heart of the moral character, for it shapes and directs the whole of our moral lives, and is indispensable to our becoming morally excellent human persons.”

Paralleling this philosophical development, contemporary Christian practice, particularly as expressed in American evangelicalism, has largely experienced the replacement of orthodox doctrine with what sociologist Christian Smith terms “moralistic therapeutic deism.”

One scholar explains that this intrusive narrator is much more than a clever narrative device in that the narrator embodies Fielding’s theology concerning the character of a God who intervenes and is active in the affairs of humankind—in other words, God’s providence.

Prudence is in human affairs what God’s sovereignty is over all of creation.

Another example is the rule among some male leaders not to meet alone with a woman, which sounds moral and wise but generally becomes impossible to practice without falling into other errors such as disrespect or discrimination.

This points to a problem in the purity culture popular today in some strains of Christianity. The movement’s well-intentioned attempt to encourage believers to remain virgins until marriage unfortunately misses the mark by inadvertently making sexual purity a means to an end (such as alluring a fine marriage partner or being rewarded with a great sex life once married) rather than being a virtue in itself.

Satire is the ridicule of vice or folly for the purpose of correction.

There is only one thing worse than being chastened: that is, not being chastened.

Prudence, like all virtues, is the moderation between the excess and deficiency of that virtue.

Perfectionism is the foil of prudence.

Unlike other virtues that are revealed under pressure, temperance is “an ordinary, humble virtue, to be practiced on a regular rather than an exceptional basis.”

One attains the virtue of temperance when one’s appetites have been shaped such that one’s very desires are in proper order and proportion.

Consumption does indeed consume us.

Inherent to temperance is balance, as evident in the Old English word temprian, which means to “bring something into the required condition by mixing it with something else.”

When we are born into a community, we are shaped by that community’s past as much as its present.

Justice is the morality of the community.

“a law that is not just does not seem to me to be a law.”

A just law is a man made code that squares with the moral law or the law of God. An unjust law is a code that is out of harmony with the moral law.

When the justice system becomes a form of entertainment, it surely is unjust. This is as true of the ancient Roman coliseum as it is of twentieth-century American public lynchings and of today’s trials by public shaming on social media.

Injustice, no matter how seemingly private, always has public consequences.

In other words, justice requires sacrifice.

Justice concerns the right ordering of not only the relationships within a community but also the parts of a person’s soul.

Courage is measured not by the risk it entails but by the good it preserves.

There’s a little bit of the prosperity gospel in all of American Christianity, and this has been true ever since the country was founded upon the very idea of that pursuit of happiness we call the American Dream.

The false bravery of a mob doesn’t constitute courage because the nature of a mob is one that reduces risk for the individuals that form it.

Courage must always be connected to a just end.

One must be vulnerable to suffering some kind of injury in order to be considered courageous.

Knowingly facing risk or danger is necessary for an act to be courageous.

Faith is the “instrument” that brings us to the Christ who saves us.

The theological virtues differ from the cardinal virtues because they are not attained by human power but come from God.

People who resist getting married by insisting that formal marriage is “just a piece of paper” ironically demonstrate just how important that paper is in their very desire to avoid it.

Both the natural passion of hope and the theological virtue of hope share the same object: “the future good that is difficult but possible to attain.”

Despair has encouraged some to place more faith in political leaders than in biblical principles.

To despair over politics—regardless of which side of the political divide one lands on—as many Christians have done in the current apocalyptic political climate, is to forget that we are but wayfarers in this land.

Watchfulness is part of hope.

We live in a society so obsessed with “the best” that good is seldom good enough. But good is good. It is very good. It is the way God characterized his own creation in Genesis.

Theological hope is an implicit surrender to the help of another—God—in obtaining a good.

Progress is an Enlightenment idea, grounded in the obvious and measurable progress of science but erroneously applied to the human condition.