More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

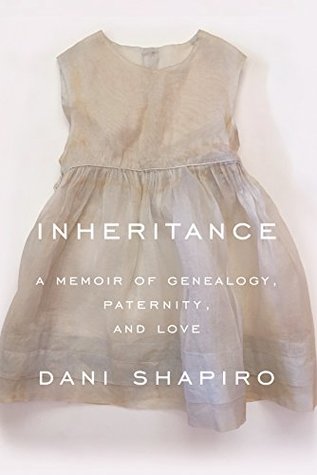

Dani Shapiro

Read between

April 7 - April 10, 2020

It turns out that it is possible to live an entire life—even an examined life, to the degree that I had relentlessly examined mine—and still not know the truth of oneself.

One person’s experience is not another’s. If five people in a family were to write the story of that family, we would end up with five very different stories.

These are truths of a sort—the truth of adhering to what one remembers.

In the absence of the empirical, I am left with a feeling central to my childhood: all my life I had the sense that something was amiss. I was different, an outsider. My family didn’t form a coherent whole. My parents and I lived in a breakable world. I had been deeply, mutely certain that there was something very wrong with me, that for all this I was to blame. Thirty-five

We never know who we will be in the burning building, the earthquake. We never know until we are faced with our own stripped-down, elemental selves.

All I knew was what I felt, which was a constant, interior ache that propelled me. At times, I felt like a sleepwalker in my own life, moving to a strange choreography whose steps I knew by heart.

“Sweetheart, this opens up a world of inclusiveness—and in the end, you have to include yourself. You aren’t bleeding color. You’re holding the light ones and the dark ones. They’re all yours. Ultimately, in all of this, Dani—the postscript is that it’s really called love.”

It is the nature of trauma that, when left untreated, it deepens over time.

I struggled to access any of my childhood or even my teenage years. I had no recollection of it as a story. And so I followed my own line of words to see where it would lead me. I understood that there were layers, striations of consciousness, inaccessible through analysis or intellect. Only in a state of half dreaming could I begin—and then only barely—to touch the truth.

But gratitude and trauma weren’t mutually exclusive.

It is a measure of true adulthood that we are able to imagine our parents as the people they may have been before us.

“To be fully alive, fully human, and completely awake is to be continually thrown out of the nest. To live fully is to be always in no-man’s-land.”

But we can never know what lies at the end of the path not taken. Other difficulties, other heartaches, other complexities would certainly have emerged.