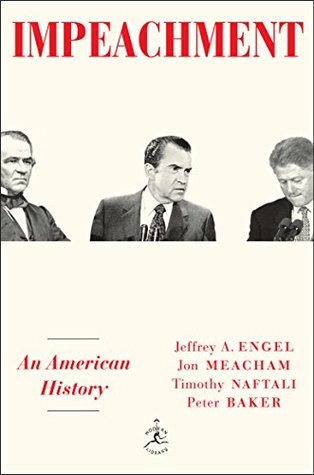

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

You know that the old aphorism “Those who do not study history are destined to repeat it” is, in fact, wrong. Those who study history are also destined to repeat it. But we are less surprised.

The collective variety and extended chronology of those who revolted and those who constructed makes for colorful history, but it muddies the average citizen’s ability to discern the era’s applicability for their own lives.

This is especially important when putting their eighteenth-century words and thinking into contemporary effect, pondering in the context of this book meaningful yet potentially debatable terms such as “treason, bribery, or high crimes and misdemeanors.”

The Constitution’s framers never expected subsequent presidents would replicate George Washington precisely. They were not fools, nor deluded into thinking him flawless or beyond reproach. Many in the room had personally seen him stumble, lose his temper, or choose the wrong course. Yet none had ever seen him put his own needs above the nation’s.

When considering what the Constitution’s authors thought about which acts or defects might warrant a president’s impeachment, therefore, one shorthand explanation can be found in asking what would George Washington not have done?8

A president who came to power under questionable circumstances—a flawed or tampered election for example—would no doubt be further incentivized to retain office by the same means.

Most supported the proposition at the start of discussion, and even more did so by the end. If unimpeachable, North Carolina’s William Davie warned, a thusly immunized president would “spare no efforts or means whatever to get himself re-elected.” A president who came to power under questionable circumstances—a flawed or tampered election for example—would no doubt be further incentivized to retain office by the same means.

Morris’s call for specificity prompted the most illuminative aspect of the entire debate for our contemporary purposes. Initial language for an impeachment clause had employed the word “malpractice” to describe a president whose actions proved himself unfit, yet the term and the synonym delegates subsequently employed more often, “maladministration,” offered significant space for interpretation and thus for legislative chicanery. If Congress could remove a president merely by judging his performance poor, a purely subjective metric, any president they did not enjoy or even like, even the most

...more

A president “may be bribed by a greater interest to betray his trust,” he explained, “and no one would say that we ought to expose ourselves to the danger of seeing the first Magistrate in foreign pay.”

“He shall be removed from his office on impeachment from the House of Representatives, and conviction by the Senate, for treason, or bribery.”54

Having now formally and for a second time agreed upon impeachment’s necessity, the group once again postponed further discussion of its practical mechanics. Yet they’d critically honed the issue, moving the criteria for impeachment away from the ambiguity of “maladministration,” a term that undoubtedly came naturally to those in the room—five states already employed this criteria for impeaching a governor. New York’s constitution offered the similarly vague “malconduct,” while North Carolina’s cited “misbehavior.” Madison had suggested “incapacity, negligence, or perfidy” as reasons for removal, which the convention’s committees for style and detail—so named because they molded the majority’s consent into usable language—revised by September 4 to read: “He shall be removed from his office on impeachment from the House of Representatives, and conviction by the Senate, for treason, or bribery.”54

Footnote

54. Madison’s Notes, July 20.

“Why is the provision restrained to Treason and bribery only?”

They were getting closer to finding the right words, but this criteria still seemed lacking. Mason argued on September 8, 1787, now nearly four months since the convention began and as patience wore thin throughout, that while their language on impeachment had once been too vague, now it seemed to his ears too limited. “Why is the provision restrained to Treason and bribery only?” he wondered. There were many “great and dangerous” offenses that might not reach the level of treason, and in Britain a celebrated case was even then ongoing whereby a chief royal administrator in India was currently on trial after impeachment for poor administration. “Attempts to subvert the constitution may not be Treason” if narrowly defined, Mason added, but they may be reason enough to fear a president’s continued tenure. He therefore moved to reinsert the once-banished word “maladministration” to the list of potential impeachable offenses.55

Footnote

55. Madison’s Notes, September 8.

Such “public wrongs,” William Blackstone, the leading legal scholar of the day, argued in 1792, “are a breach and violation of the public rights and duties, due to the whole community.” They “strike at the very being of society.”60

However less clear to our ears than treason or bribery, the term “high crimes and misdemeanors” offered no puzzle to the Constitution’s authors. Their use of the term was not a cop-out or the result of fatigue. Words mattered to the framers, who appreciated that the ones they employed would be parsed and critiqued not only by future generations, but more immediately by their peers once their convention closed. Whatever they produced in Philadelphia required ratification by the states to take effect, a reality delegates never forgot. Their honor was thus at stake not only in the document’s intent, but in its clarity as well. As Massachusetts’s Rufus King explained to his state’s ratifying convention, “It was the intention and honest desire of the Convention to use those expressions that were most easy to be understood and least equivocal in their meaning.”59

“High crimes and misdemeanors” therefore spoke clearly in their minds, and its acceptance without debate strongly suggests a shared general understanding of the phrase. It certainly was not new. A similar term, “high treasons and offenses and misprisions,” appeared in English law as early as 1386, and evolved over the ensuing centuries along a common thread: “High” offenses were those committed against the sovereign’s state, or against the people in republics where the people held sovereignty on their own. The adjective is the key. A “crime” occurred when one citizen or subject harmed another. “High crimes” were conversely those committed against the crown in a monarchy, or the people in a democracy. The term says nothing about the severity of the crime, or its consequent penalty, merely its type as one that surpassed mere criminal law, being a more fundamental assault against the body politic. Such “public wrongs,” William Blackstone, the leading legal scholar of the day, argued in 1792, “are a breach and violation of the public rights and duties, due to the whole community.” They “strike at the very being of society.”60

Footnotes

59. Gary L. McDowell, The Language of Law and the Foundations of American Constitutionalism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 225–26.

60. “At the very least,” historian Jack Rakove concluded, “English history would suggest that ‘high crimes and misdemeanors’ were regarded as high and grave indeed—posing deep threats to the survival of the constitution and even the kingdom and the preservation of essential rights and liberties.” Rakove, “Statement on the Background and History of Impeachment,” George Washington Law Review 67 (1999): 684. For “very being,” see Gary L. McDowell, “ ‘High Crimes and Misdemeanors’: Recovering the Intentions of the Founders,” George Washington Law Review 67 (1999): 641.

Put in even clearer terms, “high” crimes warranting impeachment were those a president might commit against the entire American people, a point the Constitution’s authors and their contemporaries reinforced repeatedly, in Madison’s case as a means of “defending the Community” from a corrupt or dangerous leader.

To the Constitution’s authors, therefore, a “high crime and misdemeanor,” need not violate an extant law or statute, and neither would a president who commits a common violation be guilty of a “high” offense. An impeachable offense need not be illegal at all. “Lying to the American people might be impeachable,” Yale Law School professor Akhil Amar has recently noted, “but it might not be a crime on the statute books.”

“High crimes and misdemeanors” were, another early Supreme Court justice argued, “offences which are committed by public men in violation of their public trust and duties,” and represent “injuries to the society in its political character.”

Impeachable offenses were those perpetuated with sinister intent to harm the republic for personal gain.

Malfeasance, scheming to harm the republic or to place one’s own interest above the people’s—the direct opposite of a Washingtonian virtue—was the true basis of an impeachable offense.

The president did not necessarily have to personally commit a high crime in order to be impeached, but could merely have made way for its commission, or have failed to halt it once he learned of it.

Neither does the Constitution specifically require an impeached president be removed from office, though that remains the most likely result of conviction. He could be impeached and found guilty, and then be given a lesser punishment by the Senate if they chose.

The Constitution’s framers trusted Washington not because they considered him perfect in 1787, but because they never doubted his integrity. Any ensuing president who met that standard earned the right, indeed the privilege, of serving until dismissed by his fellow citizens. Any who failed to live up to Washington’s standard, not of performance but of devotion to the community’s needs, could be impeached.

“The President has usurped the power of Congress on a colossal scale,” Charles Sumner said in early 1867, “and he has employed these usurped powers in facilitating a rebel spirit and awakening anew the dying fires of the rebellion.”68

To Grant’s dismay, Johnson also removed Philip Sheridan and Daniel Sickles, two Union generals who, as military governors, were more in line with the congressional vision of Reconstruction than they were with the president’s.69

At first the renewed effort, unfolding in the closing months of 1867, seemed likely to end as the first impeachment foray had just a few months earlier. James Ashley was still on the scene, testifying about what Chief Justice Rehnquist characterized as “his theory that every vice-president who had succeeded to the presidency had played a part in bringing about the death of his predecessor. This theory, of course, included such unlikely conspirators as John Tyler, who had succeeded William Henry Harrison in 1841, and Millard Fillmore, who had succeeded Zachary Taylor in 1850.”72 Rehnquist’s dry

...more