More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

June 29 - July 1, 2019

“Why should I bother with the Hollywood wolves?” she murmured. “I’m happy with my monsters.”

Hearing about a career beset by sexism, I could easily put myself in her shoes. I have the same pair—every woman in film has them. They’re standard issue and they’re uncomfortable as hell. Almost every day of my life as a filmmaker, I face the same kind of infuriating, misogynistic bullshit that Milicent faced in 1954. I didn’t have to imagine what it felt like for her because I constantly feel it myself.

So many women share this experience, women in every profession. We’re ignored, sexually harassed, talked down to, plagiarized and insulted in and out of the workplace. It’s worse if you’re a woman of color, a queer woman, a disabled woman, a transwoman and worse still if you’re a combination of any of these. I don’t know a single woman working in my field, or any creative field, or any field at all, who cannot relate to Milicent Patrick. It’s not just her story. It’s mine, too.

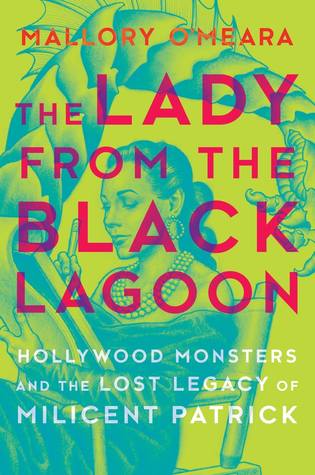

She clearly didn’t fetch coffee for anyone. She wasn’t someone’s assistant. She wasn’t being helplessly carried away in the arms of the monster. She was creating it. Looking at this picture was like being struck by lightning. It was the first time in my life I had ever seen a picture of a woman like that.

Milicent was holding a door open for me that I never realized I had considered closed. Come on, she said. We belong here, too.

As I worked my way into the business, I thought of all the girls in the world, girls who love monsters, girls who love film. These girls are sitting on the sidelines, not content to watch, but filled with a frustrated desire for momentum and creation. All these girls are potential artists, designers and filmmakers. It’s so difficult to be something if you cannot envision it. To see no way in, to see the world that you love populated exclusively with those who are not like you is devastating.

As a woman currently working in the same field she did, I can see some improvements, but not many. Certainly not enough for how many decades have passed. Every female filmmaker I know has struggled and continues to struggle against the same hardships that Milicent faced. Looking at the statistics, it is easy to see why someone would be surprised to discover that a woman was involved in designing one of the most famous movie monsters of all time.

In sixty-two years, we have improved gender equality in American film directing by four percent. At this rate, we’ll be colonizing Mars before we see an equal number of female directors.2

There has been only one female cinematographer even nominated for an Oscar. Eighty-one percent of films do not have female production designers. Ninety-nine percent of films do not have any female gaffers or key grips.3

There are people who witness these problems only in scary movies. But for much of the population, what is on the screen is merely an exaggerated version of their everyday lives. These are forces that women grapple with daily.

Women are the most important part of horror because, by and large, women are the ones the horror happens to. Women have to endure it, fight it, survive it—in the movies and in real life. They are at risk of attack from real-life monsters. In America, a woman is assaulted every nine seconds.

Women need to see themselves fighting monsters. That’s part of how we figure out our stories. But we also need to see ourselves behind-the-scenes, creating and writing and directing. We need to tell our stories, too.

Getting tattooed requires some serious dedication. Hours and hours of being stabbed with tiny needles as something hopefully beautiful and maybe meaningful is driven into you. It’s the reverse of writing. If I could get tattooed for Milicent, I could write for her, too.

It wasn’t just because some crusty old dude insulted my hero. It was because having to justify and validate a female presence in a male-dominated space was a reflex.

Feeling unbelievably lucky and desperate to earn my place, I threw myself into every task assigned to me with the charged determination of a seagull on a fallen bag of Cheetos.

No one had looked into Milicent’s story because she was a woman. Historians had dismissed her because she was a woman. Milicent was the only female in a male-dominated space. Instead of assuming that she was there for work because she was talented, these troglodytes assumed she was there for the only thing many men assume women are there for: male pleasure. In order to invalidate that assumption, they needed her artistic contributions to be proved beyond all doubt.

Oh, to be so rich that a bunch of leopards isn’t dramatic enough for you.

She was, as they say, one bad motherfucker.

In other words, get the fuck to work.

Disney: the biggest name in animation and one of the biggest names in film. They own Star Wars, your childhood emotions and by the time this book is published, probably several planets.

If you haven’t heard it, it’s the sort of string-heavy piece of music that makes you feel as if you are about to get murdered.

Getting an in at Disney was like going on a diet; everyone seemed to know how to do it and none of their advice seemed to work.

But this was still the 1940s. It was a time when a prime question of etiquette when a man hit on you was how to let him down gently.

This was the same month that Hitler invaded the Soviet Union, so there were a lot of people who understandably weren’t in the mood to go to the movies.

The problem with Paul and Milicent wasn’t just that they both worked at Disney, which discouraged interoffice relationships. The problem with Paul was that he was married.

Milicent, just like many people who are prevented from learning how to be in healthy romantic relationships while they are growing up, was about to start a lifetime habit of making poor romantic decisions.

Milicent was in her late twenties and having the first serious relationship of her life. I’m in my late twenties and cannot step outside my door without someone inquiring about when I’m going to get married and have kids. I deal with these pressures in 2018, but in the 1940s, most women Milicent’s age were already married with several children. Imagine the dizzying intensity of your first relationship, but happening while you were nearly thirty and everyone around you was pressuring you to settle down.

The problem with being the only woman to ever do something is that you have to be perfect.

I thought that for Milicent to be the first and only woman to ever design a famous monster, to be one of the first female animators, she had to be superhuman. She had to have been better than any other woman who ever wanted to design a monster. She had to have been the only one worthy enough to enter that boys’ club. This way of thinking is a maladaptation women have developed over the years to be able to deal with the fact that we’re getting passed on for jobs because we’re female. You force yourself to believe that there just haven’t been any women good enough for the job, rather than accept

...more

That’s the danger in having so few women acknowledged and hired in the film industry. Instead of looking at these women and thinking “Yes, I can get there, too!” girls can just as easily look at them all alone in a sea of men and think “They must have been perfect to get there. I never will.” It’s like being a bystander watching Odysseus sending an arrow through all those axe heads.

We need women to be allowed to be simply good at what they do. We need them on set, in meetings, behind cameras and pens and paintbrushes. We need them to be themselves, to be human: ordinary and flawed. That way, more girls can see them and think “I can do that.” That way, no one can look at them and say “She got that job because she’s beautiful. She just got that gig because she slept with someone.” Actually, she got hired because she was damn good.

Women don’t need an idol to worship.68 We need a beacon to walk toward.

Did this creep just hit on me...by offering to help dye my pubic hair? Seriously? For one thing, it takes six hours to get my hair this color. Six uncomfortable hours. That’s like trying to pick me up by offering me a pap smear. That’s the best you can come up with?

Every single woman I know who works in the film industry has not just one story like this, but many. Every single woman, regardless of age, race, body type or whether or not they look “alternative” like I do. No outfit, no dye color, no amount of “proper” looks or behavior shields you. Being a producer or a director or a famous actress doesn’t shield you. Nothing shields you.

Omitting things to make her look more like a saint would be the same impulse as covering up my tattoos in the hopes that I’ll look more respectable. I’d be perpetuating the notion that women need to be a certain way to be accepted in this industry, that women need to change themselves so that men will respect them. I’m worthy of respect, no matter what I look like. Milicent deserves to be known, no matter who she married. No woman deserves the misogyny that we experience and Milicent didn’t deserve what ultimately happened to her.

Luckily, I might not be able to walk in heels or see anything without my glasses, but I’m a wicked fast reader.

There was a memo making sure that the famous white swimsuit that Julie wears in the film was specially designed in accordance with censorship regulations and yet would still show the maximum amount of skin. My eyes rolled so hard that I was afraid they would get stuck in my frontal lobe.

I could, I’d go back in time and buy both Julie and Milicent drinks. Even when everyone is being respectful and polite, if you are the only woman in the room it’s impossible not to be acutely, uncomfortably aware of it. This feeling only intensifies if you are a marginalized woman. When I started making movies, I was terrified of being seen as too girly or too emotional. It took me years to stop monitoring my language, my behavior and the way that I dress while at work. I didn’t want to remind everyone that I was female and have them kick me out of the boys-only movie treehouse. At best it’s

...more

Women rarely get to explore on-screen what it’s like to be a giant pissed-off creature. Those emotions are written off. If a woman is angry or upset, she’ll be considered hysterical and too emotional. One of the hardest things about misogyny in the film industry isn’t facing it directly, it’s having to tamp down your anger about it so that when you speak about the problem, you’ll be taken seriously. Women don’t get to stomp around like Godzilla. Someone will just ask if you’re on your period.

Hysteria is a ridiculous, bogus medical term that is still in use today. It originated with an ancient Greek belief that all disease started in the uterus, a belief that many Republican lawmakers continue to uphold.

Women don’t get to be colossal monsters. Women don’t get to fuck shit up.

But, surprise folks, women get mad about things that don’t have to do with men. Women feel anger and isolation just as intensely as men. Women have desires for power—destructive desires—that aren’t satisfied with mean-spirited gossip and a bold lip color. Women need to be able to see themselves reflected in the monsters playing out these emotions on the big screen. Our only options shouldn’t be either banishment to a shack in the woods or growing fangs and becoming part of a bloodthirsty sister-wife troupe.

Internalized misogyny is real and it is rampant in the horror community. When you are inundated with images of beautiful women who don’t have a lot of clothes or a lot of agency,108 it implies that women have value only for their beauty. When you see only scream queens109 and monster victims, those messages sink in and they sink in deep. It puts a lot of women off the genre.

All the emotions and mechanics of scaring someone are very similar to the mechanics of making them laugh. The anticipation, the surprise. It’s usually just a matter of perspective.

Breen’s other concern involved the Creature suit and the anatomy of it. Maybe he read Arthur Ross’s version of the script and was terrified of seeing a beastly Creature member. The studio assured Breen it wouldn’t be an issue, dooming Creature fans to wonder for the rest of eternity what was under those scales.

So why, for sixty years, have monster nerds and film historians used this memo as evidence that Milicent didn’t design the suit? Why is she the only classic monster designer in contention, the only one that people deem unlikely? Because she is, well, a she.

Less than a month after the original suit was rejected by Universal executives (and everyone else), the makeup department, led by the design work and creativity of Milicent Patrick, created a totally new suit that was ready for shooting. This new suit would become the last monster to be known as a “classic” Universal monster, and one of the best known and well-loved cinematic monsters of all time. It was the first suit where the creativity and artistry wasn’t just on the head or the mask, but covered the entire body, head to claw. It became a part of film history.

So, sixty years ago, in an age before DVD special features and behind-the-scenes featurettes, when people were even more in the dark about the process of filmmaking and creating monsters, it was a historic move for Universal to send out their creature designer on tour to promote Creature from the Black Lagoon.

When you’re a teenager and a trailer for a monster movie gets removed from circulation because it’s too scary, you’ve absolutely got to see that movie.

Readers just saw a talented and beautiful lady getting recognition for something that she did. But, as they say, to the privileged, equality feels like oppression. Bud was an asshole who was used to enjoying credit for the work done by others. When one of those artists finally got their rightful moment in the spotlight, to Bud, it felt like theft.