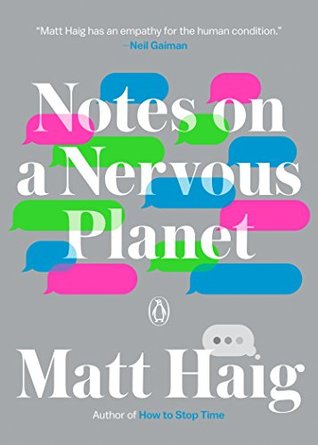

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

In T. S. Eliot’s phrase from his Four Quartets, I was “distracted from distraction by distraction.”

The values that cause us to want more than we have. To worship work above play. To compare the worst bits of ourselves with the best bits of other people. To feel like we always lack something.

Of course, news is almost designed to stress us out. If it was designed to keep us calm it wouldn’t be news. It would be yoga. Or a puppy.

And think of all the millions of children’s lives around the globe saved by vaccinations. As Nicholas Kristof pointed out in a 2017 New York Times article, “if just about the worst thing that can happen is for a parent to lose a child, that’s about half as likely as it was in 1990.”

If the modern world is making us feel bad, then it doesn’t matter what else we have going for us, because feeling bad sucks. And feeling bad when we are told there is no reason to, well, that sucks even more.

It sometimes feels as if we have temporarily solved the problem of scarcity and replaced it with the problem of excess.

Anxiety, to quote the philosopher Søren Kierkegaard, may be the “dizziness of freedom,” but all this freedom of choice really is a miracle.

But while choice is infinite, our lives have time spans. We can’t live every life. We can’t watch every film or read every book or visit every single place on this sweet earth. Rather than being blocked by it, we need to edit the choice in front of us. We need to find out what is good for us, and leave the rest. We don’t need another world. Everything we need is here, if we give up thinking we need everything.

In fact, now that I think about it, that is the chief characteristic of anxiety for me. The continual imagining of how things could get so much worse.

And it is only recently that I have been understanding how much the world feeds into this. How our mental states—whether we are actually ill or just stressed out—are to a degree products of social states. And vice versa. I want to understand what it is about this nervous planet that gets in.

As Montaigne put it, “He who fears he shall suffer, already suffers what he fears.”

All that catastrophizing is irrational, but it has an emotional power. And it isn’t just folk with anxiety who know this. Advertisers know it. Insurance sales people know it. Politicians know it. News editors know it. Political agitators know it. Terrorists know it. Sex isn’t really what sells. What sells is fear.

If you find the news severely exacerbates your state of mind, the thing to do is SWITCH IT OFF. Don’t let the terror into your mind. No good is done by being paralyzed and powerless in front of nonstop rolling news.

The whole of consumerism is based on us wanting the next thing rather than the present thing we already have. This is an almost perfect recipe for unhappiness.

To see the act of learning as something not for its own sake but because of what it will get you reduces the wonder of humanity. We are thinking, feeling, art-making, knowledge-hungry, marvelous animals, who understand ourselves and our world through the act of learning. It is an end in itself. It has far more to offer than the things it lets us write on application forms. It is a way to love living right now.

You will be happy when you have transcended earthly woes. You will be happy when you are at one with the universe. You will be happy when you are the universe. You will be happy when you are a god. You will be happy when you are the god to rule all gods. You will be happy when you are Zeus. In the clouds above Mount Olympus, commanding the sky. Maybe. Maybe. Maybe.

Maybe the point of life is to give up certainty and to embrace life’s beautiful uncertainty.

As Hamlet said to Rosencrantz, “There is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.”

We often find ourselves wishing for more hours in the day, but that wouldn’t help anything. The problem, clearly, isn’t that we have a shortage of time. It’s more that we have an overload of everything else.

To enjoy life, we might have to stop thinking about what we will never be able to read and watch and say and do, and start to think of how to enjoy the world within our boundaries.

1894, in The Kingdom of God Is Within You: The more men are freed from privation; the more telegraphs, telephones, books, papers, and journals there are; the more means there will be of diffusing inconsistent lies and hypocrisies, and the more disunited and consequently miserable will men become, which indeed is what we see actually taking place.

The word “viral” is perfect at describing the contagious effect caused by the combination of human nature and technology. And, of course, it isn’t just videos and products and tweets that can be contagious. Emotions can be, too. A completely connected world has the potential to go mad, all at once.

Understand that what seems real might not be. When the novelist William Gibson first imagined the idea of what he coined “cyberspace” in 1982’s “Burning Chrome,” he pictured it as a “consensual hallucination.” I find this description useful when I am getting too caught up in technology.

“Every one of us,” said the physicist Carl Sagan, “is, in the cosmic perspective, precious. If a human disagrees with you, let him live. In a hundred billion galaxies, you will not find another.”

Kurt Vonnegut said, decades before anyone had an Instagram account, that “we are what we pretend to be, so we must be careful who we pretend to be.”

We would do well to remember that this feeling we have these days—that each year is worse than the one previously—is partly just that: a feeling. We are increasingly plugged in to the ongoing travesties and horrors of world news and so the effect is depressing. It’s a global sinking feeling. And the real worry is that all the increased fears we feel in themselves risk making the world worse.

“When you separate yourself by belief, by nationality, by tradition, it breeds violence,” taught the philosopher Jiddu Krishnamurti.