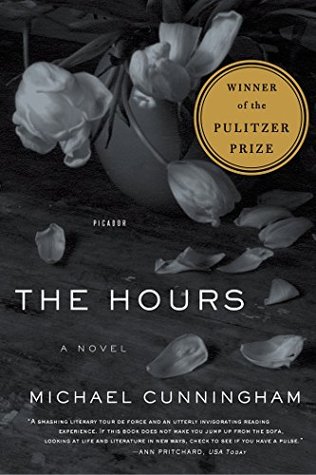

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

These days, Clarissa believes, you measure people first by their kindness and their capacity for devotion. You get tired, sometimes, of wit and intellect; everybody’s little display of genius.

She has aged dramatically, just this year, as if a layer of air has leaked out from under her skin. She’s grown craggy and worn. She’s begun to look as if she’s carved from very porous, gray-white marble. She is still regal, still exquisitely formed, still possessed of her formidable lunar radiance, but she is suddenly no longer beautiful.

and when she glanced over at this new book on her nightstand, stacked atop the one she finished last night, she reached for it automatically, as if reading were the singular and obvious first task of the day, the only viable way to negotiate the transit from sleep to obligation.

the scattering of pigeons with feet the color of pencil erasers

these two girls will grow to middle and then old age, either wither or bloat; the cemeteries in which they’re buried will fall eventually into ruin, the grass grown wild, browsed at night by dogs; and when all that remains of these girls is a few silver fillings lost underground the woman in the trailer, be she Meryl Streep or Vanessa Redgrave or even Susan Sarandon, will still be known.

She has learned over the years that sanity involves a certain measure of impersonation, not simply for the benefit of husband and servants but for the sake, first and foremost, of one’s own convictions.

“Hello,” says Julia, behind him. Not “hi.” She has always been a grave little girl, smart but peculiar, oversized, full of quirks and tics.

Clarissa holds Julia, and quickly releases her. “How are you?” she asks again, then instantly regrets it. She worries that it’s one of her tics; one of those innocent little habits that inspire thoughts of homicide in an offspring. Her own mother compulsively cleared her throat. Her mother prefaced all contrary opinions by saying, “I hate to be a wet blanket, but—” Those things survive in Clarissa’s memory, still capable of inspiring rage, after her mother’s kindness and modesty, her philanthropies, have faded.

Clarissa Vaughan is not the enemy. Clarissa Vaughan is only deluded, neither more nor less than that. She believes that by obeying the rules she can have what men have.

She thinks of how much more space a being occupies in life than it does in death; how much illusion of size is contained in gestures and movements, in breathing. Dead, we are revealed in our true dimensions, and they are surprisingly modest.

“But there are still the hours, aren’t there? One and then another, and you get through that one and then, my god, there’s another. I’m so sick.”

smell of his flesh—a smell with elements of iron, elements of bleach, and the remotest hint of cooking, as if deep inside him something moist and fatty were being fried.