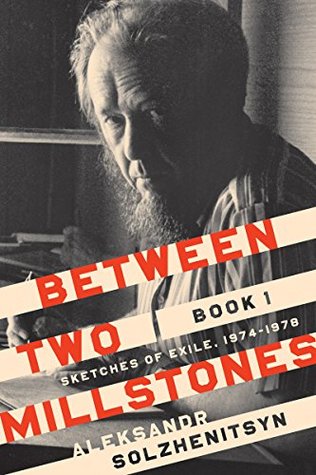

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

February 12 - February 20, 2019

Solzhenitsyn was indeed caught “between two millstones”: a totalitarian regime in the East that posed a grave and immediate threat to humanity, and the often frivolous forces of Western “freedom” that had lost a sense of dignity and high purpose. He had a new tension-ridden mission: to write with force, clarity, and artfulness about the Russian twentieth century while doing his best to warn the West about the pitfalls of a free society caught up in the cult of comfort and increasingly unwilling to defend itself against the march of evil.

In June and July of 1975, Solzhenitsyn came to the United States for the first time, addressing meetings of the AFL-CIO in Washington and New York, respectively. On those occasions, he displayed great “passion and conviction,” “thrusting a spear into the jaws and ribs” of his “nemesis, the Soviet Dragon.” Yet he began to have doubts that his “warnings to the West” were succeeding in conveying the full truth about Communist totalitarianism (and Western complicity in its spread) to a West weighted by materialism and an excessive engrossment in everyday life. In his own word, he had become

...more

Solzhenitsyn did not become embittered. Rather, he strove to connect to those healthy elements in Western and American society that were still open to the old verities and to the truth about the human soul.

Solzhenitsyn writes of the dramatic importance of the two months he spent in 1976 examining the enormously rich document collections at the Hoover Institution in Palo Alto, California, bearing on the events in the Russia of 1917. For the first time, he discovered the full truth about the February revolution of 1917: rather than being a liberating outburst of freedom as he and so many other historians had supposed, he came to see nothing but “baseness, meanness, hypocrisy, plebeian uniformity, and suppression of people with other points of view” that took place. The first February revolution of

...more

And when Solzhenitsyn reminded Americans at Harvard in June 1978 that freedom demands voluntary self-limitation, that it requires civic courage and lucidity about the totalitarian threat, when he dared to criticize the superficiality and irresponsibility of the free press, he was once again denounced against all evidence as a “fanatic,” “a fierce dogmatic,” “a mind split apart.” Solzhenitsyn thought Americans welcomed criticism but soon discerned that intellectual elites only welcomed criticism that came from the Left.

After a great upheaval passes, you feel it even more.

Today’s prosperous world is moving ever further from natural human existence, growing stronger in intellect but increasingly infirm in body and soul.

The Dragon’s jaws will not relinquish you twice.

Be sweet and you shall be devoured, be bitter and you shall be spat out. I preferred the second option. (Furthermore, there were letters in every language—from the major ones all the way to Latvian and Hungarian; people seemed to think that no sooner had I set foot in the West I already had a fully staffed office at hand.)

If I stop writing now and let myself be trapped, freedom would lose all meaning for me.

I had conducted myself as the struggle demanded until the very last moment in the Soviet Union. I had not slackened in the West either, but could not bring myself to submit to political calculation. If I was now truly in the free world, I wanted to be free: free of all the harassment from the press, free of all the invitations and public appearances. All my refusals were a literary self-defense mechanism, the same spontaneous and unconsidered mechanism (definitely a mistaken one from a pragmatic point of view) that, after Ivan Denisovich had been published, had kept me from going to the

...more

What hurt them most was that I was not a passionate admirer of the West, “not a democrat”! And yet I am much more of a democrat than the New York intellectual elite or our dissidents are: in my view, democracy means the genuine self-government of the people, from the bottom up, while these people see it as being the rule of the educated classes.

But my heart was not at peace. Zurich is an exceptionally beautiful city, but as I walked through its streets I felt a sadness within me. Not that this had anything to do with Zurich itself, it was rather my basic aversion to the excesses and carelessness of the West.

The speech I had prepared, however, was much too complicated. I was still trapped in the flight between two worlds, not having yet acquired points of reference or an understanding of intellectual expectations; but I was already being besieged by the triumphant Western materialism that was eclipsing all spirituality. Consequently, I had prepared a speech for the Italian journalists that was like trying to push water uphill with a rake, a speech that far overshot the mark.

The task of evaluating one’s past and tracing out the future becomes easier. I only had to raise my eyes from my sheet of paper and would see before me one of the amazingly beautiful cirques with its blend of steeply sloping meadows, its forested islets and slivers, its winding farming paths and its farm structures.

From Under the Rubble

The idea of having days off was rare in Soviet life, and in my own life I do not recall there ever having been such a concept or such a situation, except on my fiftieth birthday. I never took Sundays off, nor holidays, or had a day without goals to fulfill.

I say farewell to Europe not only because I am leaving, but I fear we are all saying farewell to Europe as we knew and loved her these past centuries. Florence is so overwhelmed with refuse and stench that even early in the morning the city feels dirty and chaotic. (This had already started back when our poet Aleksandr Blok lived here: “Your cars are rattling with rust / Hideous your house and home / From all over Europe comes sallow dust / You betrayed yourself, you alone!”)

We are led by our conviction that there is no such thing as “general freedom,” but only various individual freedoms, each associated with our obligations and self-restraint. On an almost daily basis, the violence of our times proves to us that the guaranteed freedom of person or state is impossible without discipline and honesty, and it is precisely on such grounds that our community has managed to perpetuate its incredible vitality through the centuries. Our community never gave itself over to the folly of total freedom, and never made a pact with inhumanity with the view of making the state

...more

Democracy without mettle, democracy that seeks to grant rights to each and every individual, degenerates into a democracy of servility. The soundness of a system of government does not depend on the perfection of the articles of a constitution, but on the ability of leaders to bear its burdens. We sell democracy short if we elect weak individuals to its government.

This was no ordinary April, meanwhile, but the April of 1975, a dangerous moment for the West (though the West was barely aware of it), the United States having fled Indochina. Only ten days before the election at Appenzell the naïve Western press had reported: “The people of Phnom Penh have welcomed the Khmer Rouge with joy.”

The Swiss Confederation, established in 1291, is in fact now the oldest democracy in the world. It did not spring from the ideas of the Enlightenment, but directly from the ancient forms of communal life.

How difficult it is, when living in prosperity, to be resolute and make sacrifices!

While we fought unto death, suffering the weight of the Soviets’ idol of stone, from the West a unanimous cry of approval came to me, and from that same West there stretched grasping hands, seeking to make a profit from my books and my name, not caring a fig for my books or our struggle.

Was it that people in the West were worse than people back in Russia? Of course not. But when the only demands on human nature are legal ones, the bar is much lower than the bar of nobleness and honor (those concepts having in any case almost vanished now), and so many loopholes open up for unscrupulousness and cunning. What the law compels us to do is far too little for humaneness: a higher law should be placed in our hearts, too. I simply could not get used to the cold wind of litigation in the West.

But when it comes to hefty, overfed, dimwitted hippies, Canada in no way lags behind the rest of the civilized world: they lie about in flowerbeds sunning themselves, and lounge on park benches in the middle of the workday, chatting, smoking, sleeping.

To me it was clear that Communism could not last forever. It was decaying from within, chronically ill, but on the outside seemed immensely powerful, marching forward with great strides! And it was marching forward because the hearts of the affuent people of the West were timid, timid due to that very prosperity. But with Communists, as with thugs, you must show unrelenting toughness. In the face of toughness they will relent, toughness they respect.

(And yet Napoleon did say: “The most powerful weapon, after guns, is repetition.”)

There might be no similarity in appearance between Russia and Spain, but there are unexpected similarities of character: courage, openness, disorganization, hospitality, extremes of godliness and ungodliness.

No matter how much Spanish blood was spilled in the Civil War, Spain would have had to sacrifice twenty times more if the Reds had won. What they had had for the last thirty-seven years was not a dictatorship: I, with my experiences from the Soviet Union, could tell them the true meaning of dictatorship, the true meaning of Communism and the persecution of religion. I was a most useful witness for the people of Spain.

(Indeed, one might ask if a broad anti-Communism even exists in Western society?—It does not.)

Looking back, it is amazing that the unanimous support that had sustained me in my battle against the Soviet Dragon—the support of the Western press and Western society, and even from within the Soviet Union—that incredible and unjustified groundswell that lifted me, had been triggered by a mutual lack of understanding. I, in fact, suited the all-powerful opinion of the Western political and intellectual elite as little as I did the Soviet rulers, or indeed the Soviet pseudo-intellectuals.

It was July 1977. I was feeling smothered, bewildered: how were we to live in the West? The millstone of the KGB had never tired of crushing me, I was used to that, but now a second millstone, the millstone of the West, was descending upon me to grind me all over again (and not for the first time). How were we to live here? In every business, financial, and organizational matter in the West, I always find myself blundering, backed into a corner, pulling the short straw, everything in utter confusion, so that there are moments when I simply despair: it is as if I had lost all reason, no longer

...more

A sense of responsibility before God and society has fallen away. “Human rights” have been so exalted that the rights of society are being oppressed and destroyed. And above all, the press, not elected by anyone, acts high-handedly and has amassed more power than the legislative, executive, or judicial power. And in this free press itself it is not true freedom of opinion that dominates, but the dictates of the political fashion of the moment, which lead to a surprising uniformity of opinion. (It was on this point that I had irritated them most.)

My goal in the entire book, as in all my books, was to show what a human being could be turned into—to show that the line between good and evil is constantly shifting within the human heart.

in Lidia Ezherets’s roomy apartment, the

The Communist system is a disease, a plague that has been spreading across the earth for many years already, and it is impossible to predict what peoples will yet be forced to experience this disease firsthand. My people, the Russians, have been suffering from it for sixty years already; they long to be healed. And the day will come when they are indeed healed of this Soviet disease. On that day I will thank you for being good friends and neighbors, and will go back to my homeland.