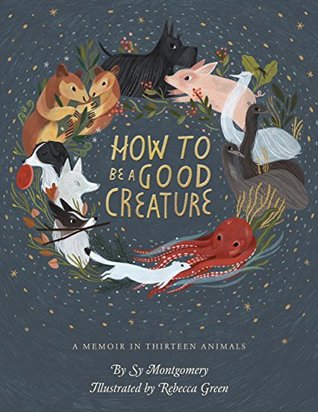

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

October 12 - October 13, 2018

most of my teachers have been animals. What have animals taught me about life? How to be a good creature.

I am still learning how to be a good creature. Though I try earnestly, I often fail. But I am having a great life trying—a life exploring this sweet green world—and returning to a home where I am blessed with a multispecies family offering me comfort and joy beyond my wildest dreams.

Many young girls worship their older sisters. I was no exception. But my older sister was a dog, and I—standing there helplessly in the frilly dress and lacy socks in which my mother had dressed me—wanted to be just like her: Fierce. Feral. Unstoppable.

I would stare blankly at an adult I had seen many times, unable to

place them, unless one of my parents could remind me of their pet.

A Scottie puppy is like a terrible two-year-old tot on steroids and gifted with an almost unnatural indestructibility.

A small dog had done this with her face. I was impressed early on that Molly was a powerful being, worthy of deep respect.

Eventually my parents figured out we could blink the front porch lights on and off to signal that we would like her to come home. It was merely a suggestion—the way my father felt about traffic lights (he called a red light “just a suggestion”). Molly would come home when she felt like it.

suburbs, I knew there was a vivid, green, breathing world out there, bustling with the busy lives of birds and insects, turtles and fish, rabbits and deer.

freedom. Surrounded with talented editors, smart colleagues, and good friends, I lived in a little cabin in the woods with five ferrets, two lovebirds, and the man I loved, Howard Mansfield, a brilliant writer whom I’d met in college. I was happy.

I wanted to reassure the birds: It’s only me; I’m harmless. I reckoned they could see me long before I could see them.

What do they do all day? I wondered. On one of our rare trips to Adelaide, I’d visited the university library. Nobody had published a scientific paper describing the behavior of a group of wild emus before. So, while I continued the seed germination experiments (and yes, seeds did germinate more quickly after passing through an emu’s gut), chronicling the birds’ daily lives became the new focus of my work.

I, too, looked to Black Head for guidance. If I could catch his eye, with a glance I’d try to assess

whether he was happy with me following everyone or not. In a sense, I was asking his permission to follow. And yet in another way, by acknowledging him as the leader of the group, I made him my leader too.

Though in dirty clothes, my uncombed hair matting like the fur on a stray dog, when bathed in the sight of this giant, alien flightless bird, I felt beautiful for the first time in my life.

It wasn’t the data on these emus I wanted, I realized. I simply wanted to be with them.

What mattered was it was dark and safe, and we were together as they slept.

boss. Now I knew I would spend the rest of my life writing about animals, going wherever their stories would take me. Molly, who had saved my life, had shown me my destiny. The emus, on their tall, impossibly backwards-bending legs, had let me stroll with them for the first steps along the path.

After a military childhood of frequent moves, I felt like I had finally found a home.

But now Howard was desperate to cheer me up. The best thing he could think of to do the trick was adopt a baby pig.

We would both squeal with delight upon contact.

“I’m a vegetarian and my husband is Jewish,” I’d explain. “We’re certainly not going to eat him. But we might send him abroad for university studies . . .”

So, anchored to our beloved home by a growing pig, like most young married couples who begin settling down, we decided it was time to enlarge our family.

Christopher soon greeted the girls with distinctive soft grunts he used for no other visitors.

which were shared among the kids and the pig. For the first time in my life, I learned how much fun it is to play with children, and looked forward to it every day.

Somehow, they knew: though we weren’t all related, thanks to Christopher Hogwood, our two multispecies households had become one unit.

At home, everyone so admired him that he garnered write-in votes at every election.

After a lifetime of moving, Christopher Hogwood helped give me a home.

And when she stood on the mat of silk she had spun from her own body at the mouth of her burrow, she could pick up the vibrations of the footfalls of the tiniest insect.

She knew we were there, Sam assured us. But she was unafraid.

All three of us enjoyed interacting so intimately with this small wild animal. She made us feel even more at home at Emerald Jungle Village.

That day, I heard a little girl in neat pigtails murmur, almost under her breath, “Elle est belle, le monstre.” She is beautiful, the monster.

Our chicks grow up in my home office, cheerfully perching on my lap and shoulders as I write, or racing around the floor after one another, spreading wood shavings and feather dust. They occasionally add to my prose by walking across my computer keyboard.

They followed Howard and me as we did yard work, commenting constantly in their lilting chicken voices: Here I am. Where are you? Any worms? Oh, a bug! Over here . . .

Playing with Tess meant multitasking love.

Of course, they always had been. To me, one of the most heartbreaking conditions of life on Earth is that most of the animals we love, with the exception of some parrots and tortoises, die so long before we do.

Tess. I never feared dying. Death was just one more new place to go.

I believed if there was a heaven, and if I went there, I would be reunited with all the animals I had loved.

I missed traveling in the slipstream of her superpowers. I was sad—but Tess was not.

Tess could follow my heat and my scent at first. Later, we remained touching at all times. And I was honored, after our years together, to receive the gift of her graceful, trusting reliance on me, as I had once relied on her, to navigate through the dark. Never before had anyone relied on me so completely. Never before had anyone loved me more deeply. And never before had I experienced grace so profound.

Tess never lost her superpowers. She had simply brought them back and handed them to me, like the Frisbee at night.

If I had dropped dead, it would have been fine with me, but I didn’t want to

wreck the expedition for everyone else.

At our campsite, ancient tall trees stood guard over our tents like benign wizards bearded in moss.

John Ruskin, a nineteenth-century British art critic, called moss—humble, soft, and ancient—“the first mercy of the Earth.”

“The Earth feels so new here,” I wrote in my field journal. “No wonder we can sometimes feel its molten, beating heart.”

Would we know her? What if I picked the wrong dog, and failed my stalwart, lionhearted Tess, who had come all the way back from the dead to try to show me the right one?

She was also a counter surfer. No food she could reach was safe.

I couldn’t help but laugh. Howard called her Little Sally Rap Sheet.

I felt whole again. Sally made me unspeakably happy. I loved the softness of her fur, the cornmeal-like scent of her paws, the rolling cadence of her gait, the gusto with which she ate (even the stick of butter softening for the dinner table and the bowl of cereal abandoned for a moment to take a phone call). I loved the way she’d eviscerate the stuffed toys I would always bring her from my travels—delighting in the destruction of a blue shark, a red rhino, and one stuffed hedgehog after another. I loved her tall ears.