More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Jemar Tisby

Read between

December 16, 2020 - January 5, 2021

The failure of many Christians in the South and across the nation to decisively oppose the racism in their families, communities, and even in their own churches provided fertile soil for the seeds of hatred to grow. The refusal to act in the midst of injustice is itself an act of injustice. Indifference to oppression perpetuates oppression.

History and Scripture teaches us that there can be no reconciliation without repentance. There can be no repentance without confession. And there can be no confession without truth.

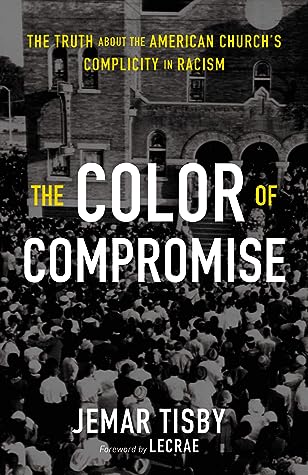

This book tells the truth about racism in the American church in order to facilitate authentic human solidarity.

racism is a system of oppression based on race.

Another definition explains racism as prejudice plus power. It is not only personal bigotry toward someone of a different race that constitutes racism; rather, racism includes the imposition of bigoted ideas on groups of people.

Historically speaking, when faced with the choice between racism and equality, the American church has tended to practice a complicit Christianity rather than a courageous Christianity. They chose comfort over constructive conflict and in so doing created and maintained a status quo of injustice.

Yet justice for one group can open pathways for equality to other groups.

One notable theme is that white supremacy in the nation and the church was not inevitable. Things could have been different.

History demonstrates that racism never goes away; it just adapts.

The goal is to build up the body of Christ by “speaking the truth in love,” even if that truth comes at the price of pain.

Black Christians saw in Scripture a God who “sits high and looks low”—one who saw their oppression and was outraged by it.

Jumping ahead to the victories means skipping the hard but necessary work of examining what went wrong with race and the church.

In 2 Corinthians 7:10, Paul says, “For godly grief produces a repentance that leads to salvation without regret” (ESV).

“As it is, I rejoice, not because you were grieved, but because you were grieved into repenting” (2 Cor. 7:9 ESV).

Perhaps even more subtly, the free market became a form of economic gospel truth for Pepperdine. Spurred by the open-market business philosophy of its founder and a growing number of Christian entrepreneurs, the school taught its students to distrust unionism and federal intervention, specifically in the form of welfare programs geared toward the poor.36 Schools such as Pepperdine indoctrinated a new generation of white Christians with ideas that would lend educational and ideological support to an individualistic approach to race relations and that would lead to an aversion to government

...more

the Roosevelt administration sought to exploit black people as soldiers while simultaneously maintaining racial segregation, effectively forging two separate but unequal militaries.

The Veteran’s Administration, created to disburse benefits to returning soldiers, denied mortgages to black soldiers and funneled these veterans into lower-level training and education rather than into four-year colleges.

Through a series of rules and customs, government employees and real estate agents have actively engineered neighborhoods and communities to maintain racial segregation.

Neighborhoods with any black people, even if the residents had stable middle-class incomes, were coded red, and lenders were unlikely to give loans in these areas. This practice became known as redlining.

For much of the twentieth century, “restrictive covenants” provided a legal, race-based mechanism to exclude black people from purchasing homes in white communities. “Private but legally enforceable restrictive covenants . . . forbade the use or sale of a property to anyone but whites.”43 These restrictive covenants, which also dictated details such as what color residents could paint their houses, effectively kept black people out of communities, especially new growth suburbs, for decades. Even after the 1948 Supreme Court ruling in Shelley v. Kraemer forbidding these racial covenants, real

...more

‘We can solve a housing problem, or we can try to solve a racial problem. But we cannot combine the two.’ ”45 In this way, private businesses participated in forming the racially segregated housing patterns that have permeated municipal areas in every region of the United States, not just the South.

Easby Wilson and his wife finally decided to move when their son started waking up in the middle of the night with “nervous attacks.” A psychologist told them that their son, Raymond, “risked ‘becoming afflicted with a permanent mental injury’ ” if they stayed and endured more assaults.47

Blockbusting is an example of how some agents leveraged racism for their personal advantage.

“In many cases, churches not only failed to inhibit white flight but actually became co-conspirators and accomplices in the action.”

Rather than stay and adapt to a new community reality or assist in integrating the neighborhood, many white churches chose to depart the city instead.

With police in riot gear waiting in the wings, counterprotesters waved Confederate flags and held signs saying, “The Only Way to End Niggers Is to Exterminate.”56 As King threaded his way through the throng, someone from the crowd threw a rock, striking him behind the ear. King’s knees folded, and he sank to the ground, dazed. Resolute and determined, King stood back up and continued marching. That evening King told reporters, “I have never seen such hate. Not in Mississippi or Alabama. This is a terrible thing.”57

Yet the very conspicuousness of white supremacy in the South has made it easier for racism in other parts of the country to exist in open obscurity. Christians of the North have often been characterized as abolitionists, integrationists, and open-minded citizens who want all people to have a chance at equality. Christians of the South, on the other hand, have been portrayed as uniformly racist, segregationist, and antidemocratic. The truth is far more complicated.

Compromised Christianity transcends regions. Bigotry obeys no boundaries. This is why Christians in every part of America have a moral and spiritual obligation to fight against the church’s complicity with racism.

But what we must not ignore is that while segregationist politicians spewed forth words of “interposition and nullification,”23 while magazines published editorials calling civil rights activists Communists, and while juries acquitted violent racists of criminal acts, none of this would have been possible without the complicity of Christian moderates.

When these efforts failed, and one or two black families moved into the neighborhood, many of the white residents moved out. Churches shut their doors or fled to the all-white suburbs.37 Today, even more than fifty years later, many of these communities remain almost as racially segregated now as they were then.

Schools also became a battleground for Christians committed to segregation. Some Christian parents, faced with the unconscionable prospect of little white girls attending school with little black boys and eventually growing up, falling in love, and having brown babies, started “segregation academies.” Because these were private schools, these institutions did not have to abide by the Brown v Board mandate for racial integration, which only applied to public schools.

This picture, and hundreds of others like it, subtly reinforced the idea that Jesus Christ was a European-looking white man, and many added to that the assumption that he was a free-market, capitalist-supporting American as well.

Back in 1961, King spoke at the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, the flagship school of the largest Protestant denomination in the United States. Although he was there at the invitation of a professor, powerful Southern Baptists opposed his visit. As historian Taylor Branch wrote in his biography of King, “Within the church, this simple invitation was a racial and theological heresy, such that churches across the South rescinded their regular donations to the seminary.”

Yet a few years later, as the civil rights movement continued and King became an even better-known figure, Graham advised King and his allies to “put on the brakes.” Like the white moderates King wrote about in his letter from jail, Graham never relented from the belief that “the evangelist is not primarily a social reformer, a temperance lecturer or a moralizer. He is simply a keryx, a proclaimer of the good news.”

he railed against government enforced integration. Criswell stated that desegregation is “a denial of all that we believe in.” He went on to say that Brown v Board was “foolishness” and an “idiocy,” and he called anyone who advocated for racial integration “a bunch of infidels, dying from the neck up.”52 Notably, Criswell did moderate some of his stances and statements later in life, but not before thousands of Christians in his own congregation and tens of thousands more of his followers nationwide had absorbed his views of civil rights and activists like King.

As he sat in his room he could hear his white peers down the hall, laughing. Then came the awful news that King was dead. As soon as commentators reported this news, the young black man “could hear white voices down the hall let out a cheer.” Reflecting back on this experience, Weary said, “Laughing at Dr. King’s death was just like laughing at me—or at the millions of other blacks for whom King labored.”53 Remarkably, Weary did not let the hate of others consume him. He has spent his life working for racial reconciliation in his home state, Mississippi.

“Absent from their accounts is the idea that poor relationships might be shaped by social structures, such as laws, the ways institutions operate, or forms of segregation. . . . They often find structural explanations irrelevant or even wrongheaded,” Emerson and Smith explain.

Sixty-two percent of white evangelicals attribute poverty among black people to a lack of motivation, while 31 percent of black Christians said the same.

And just 27 percent of white evangelicals attribute the wealth gap to racial discrimination, while 72 percent of blacks cite discrimination as a major cause of the discrepancy.

The differing cultural tool kits applied by black and white Christians help illuminate some of the conflicts over racial justice at ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Even in the past few years, the list of black human beings who have become hashtags has grown ever longer—Stephon Clark, Philando Castile, Freddie Gray, Walter Scott, Jamar Clark, Rekia Boyd, Eric Garner, Sandra Bland, Tamir Rice, to name just a few.

Activists have deployed the phrase black lives matter because the cascade of killings indicated that black lives did not, in fact, matter.

Black lives matter does not mean that only black lives matter; it means that black lives matter too. Given the racist patterns of devaluing black lives in America’s past, it is not obvious to many black people that everyone values black life. Quite the contrary, the existential equality of black people must be repeatedly and passionately proclaimed and pursued, even in the twenty-first century.

The words black lives matter also function as a cry of lament.

Black lives matter presents Christians with an opportunity to mourn with those who mourn and to help bear the burdens that racism has heaped on black people (Rom. 12:15).

And when Lecrae said he was praying for Ferguson, the first response in a long thread of replies reads “#Pray4Police” as if in rebuttal to the need to pray for the black people affected by the tragedy.

“But mention ‘justice’ and that wall of evangelical troops splits like the Red Sea and turns against itself. Men who worked as fellow combatants in the traditional ‘culture war’ begin to suspect and even attack one another when ‘justice’ becomes the topic.”

As Anyabwile pointed out in his blog post, Johnson’s implication was that speaking about racial justice somehow indicated a drift away from the “true” gospel.

“Black lives matter is not a mission of hate. It is not a mission to bring about incredible anti-Christian values and reforms to the world,” she informed the audience of 16,000 college students. As if speaking about black lives matter head on was not enough, she went further still and criticized the primacy of abortion in the evangelical canon of sins. “We can wipe out the adoption crisis tomorrow,” she said. “But we’re too busy arguing to have abortion banned. We’re too busy arguing to defund Planned Parenthood.”