More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Jemar Tisby

Read between

February 7, 2020 - January 18, 2021

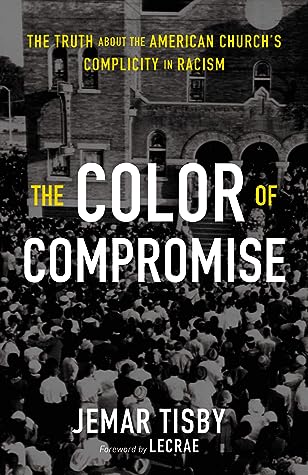

truth. The Color of Compromise is about telling the truth so that reconciliation—robust, consistent, honest reconciliation—might occur across racial lines.

Carl Hempel liked this

One of the reasons churches can’t shake the shackles of segregation is that few have undertaken the regimen of aggressive treatment the malady requires.

Carl Hempel liked this

This book is about revealing racism. It pulls back the curtain on the ways American Christians have collaborated with racism for centuries. By seeing the roots of racism in this country, may the church be moved to immediate and resolute antiracist action.

Carl Hempel liked this

Although there have been notable exceptions, and racial progress in this country could not have happened without allies across the color line, white people have historically had the power to construct a social caste system based on skin color, a system that placed people of African descent at the bottom. White men and women have used tools like money, politics, and terrorism to consolidate their power and protect their comfort at the expense of black people. Christians participated in this system of white supremacy—a concept that identifies white people and white culture as normal and

...more

As historian Carolyn DuPont describes it, “Not only did white Christians fail to fight for black equality, they often labored mightily against it.”11

In reality, white Christians have often been the current, whipping racism into waves of conflict that rock and divide the people of God. Even if only a small portion of Christians committed the most notorious acts of racism, many more white Christians can be described as complicit in creating and sustaining a racist society.

At several points in American history—the colonial era, Reconstruction, the demise of Jim Crow—Christians could have confronted racism instead of compromising. Although the missed opportunities are heartbreaking, the fact that people can choose is also empowering.

The malleability and impermanence of racial categories help explain how the American church’s compromise with racism has become subtler over time. History demonstrates that racism never goes away; it just adapts.

By contrast, courageous Christianity embraces racial and ethnic diversity. It stands against any person, policy, or practice that would dim the glory of God reflected in the life of human beings from every tribe and tongue.

Missionaries, ministers, and slaveowners encouraged African Christians in America to be content with their spiritual liberation and to obey their earthly masters.

Black people immediately detected the hypocrisy of American-style slavery. They knew the inconsistencies of the faith from the rank odors, the chains, the blood, and the misery that accompanied their life of bondage. Instead of abandoning Christianity, though, black people went directly to teachings of Jesus and challenged white people to demonstrate integrity.

When Le Jau was able to persuade African slaves to adopt the Christian religion as their own, he confirmed their profession by baptizing them. The vows he made the slaves recite show how European missionaries maintained a strict separation between spiritual and physical freedom. “You declare in the presence of God and before this congregation that you do not ask for holy baptism out of any design to free yourself from the Duty and Obedience you owe to your master while you live, but merely for the good of your soul and to partake of the Grace and Blessings promised to the Members of the Church

...more

A corrupt message that saw no contradiction between the brutalities of bondage and the good news of salvation became the norm.

Evangelicalism focused on individual conversion and piety. Within this evangelical framework, one could adopt an evangelical expression of Christianity yet remain uncompelled to confront institutional injustice.

Harsh though it may sound, the facts of history nevertheless bear out this truth: there would be no black church without racism in the white church.

The divide between white and black Christians in America was not generally one of doctrine. Christians across the color line largely agreed on theological teachings such as the Trinity, the divinity of Jesus, and the importance of personal conversion. More often than not, the issue that divided Christians along racial lines related to the unequal treatment of African-descended people in white church contexts.

White evangelists compromised the Bible’s message of liberation to make Christianity compatible with slavery. They sought to allay the trepidation of enslavers by spiritualizing Christian equality—spiritual freedom did not change one’s status as slave or free.

As Charles F. Irons wrote in The Origins of Proslavery Christianity, “Sunday morning only became the most segregated time of the week after the Civil War. Before emancipation, black and white evangelicals typically prayed, sang, and worshiped together.”13 Yet this interracial interaction did not come from the egalitarian aspirations of white Christians; rather, interracial congregations were an expression of paternalism and a means of controlling slave beliefs and preventing slave insurrection.

One of the theological legacies of the Second Great Awakening was postmillennialism, the view that Christ would return only after an extended era of peace and justice. Christians saw it as their duty to usher in this millennium and to prepare for Jesus’s return by reforming society and tamping down its vices. As a result, dozens of new Christian-led social reform organizations sprang into being. These societies addressed issues related to poverty, orphan and widow care, alcoholism, and abolitionism. The loose organization of these societies became known as the “Benevolent Empire.”

Yet despite energetic efforts at reform, slavery remained the most intractable issue of American life. A majority of white Christians refused to take a definitive stand against race-based chattel slavery, and this complicity plagued the church and created stark contradictions. Segregation and inequality defined most of American Christianity—even in an age of great revivals. For example, many black people attended the Cane Ridge Revival, but they were forced to meet in a separate area apart from the white worshipers. One of the