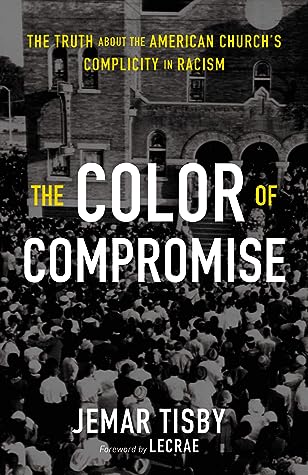

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Jemar Tisby

Read between

June 30, 2020 - January 30, 2021

The failure of many Christians in the South and across the nation to decisively oppose the racism in their families, communities, and even in their own churches provided fertile soil for the seeds of hatred to grow. The refusal to act in the midst of injustice is itself an act of injustice. Indifference to oppression perpetuates oppression. History and Scripture teaches

Even when Christians realize the need for change, they often shrink back from the sacrifices that transformation entails.

Christians participated in this system of white supremacy—a concept that identifies white people and white culture as normal and superior—even if they claim people of color as their brothers and sisters in Christ.

Historically speaking, when faced with the choice between racism and equality, the American church has tended to practice a complicit Christianity rather than a courageous Christianity. They chose comfort over constructive conflict and in so doing created and maintained a status quo of injustice.

The Virginia Assembly took the initiative to enact a new law. Despite the established tradition, the assembly decided that baptism would not confer freedom upon their laborers. Instead, these Africans would remain in physical bondage even after their conversion. Missionaries, ministers, and slaveowners encouraged African Christians in America to be content with their spiritual liberation and to obey their earthly masters.

Unwilling to confront the evil of this institution, some churches lost their prophetic voices, and those who did speak up were drowned out by the louder chorus of complicity.

The church, which prioritizes the love of God and love of neighbor, capitulated to the status quo by permitting the lifetime bondage of human persons based on skin color.

It’s not that members of every white church participated in lynching, but the practice could not have endured without the relative silence, if not outright support, of one of the most significant institutions in America—the Christian church.

“Both Jesus and blacks were ‘strange fruit,’ ” he wrote. “Theologically speaking, Jesus was the ‘first lynchee,’ who foreshadowed all the lynched black bodies on American soil.”

Being complicit only requires a muted response in the face of injustice or uncritical support of the status quo.

Christian complicity with racism in the twenty-first century looks different than complicity with racism in the past. It looks like Christians responding to black lives matter with the phrase all lives matter. It looks like Christians consistently supporting a president whose racism has been on display for decades. It looks like Christians

telling black people and their allies that their attempts to bring up racial concerns are “divisive.” It looks like conversations on race that focus on individual relationships and are unwilling to discuss systemic solutions. Perhaps Christian complicity in racism has not changed much after all. Although the characters and the specifics are new, many of the same rationalizations for racism remain.

The church today must practice the good that ought to be done. To look at this history and then refuse to act only perpetuates racist patterns. It is time for the church to stand against racism and compromise no longer.