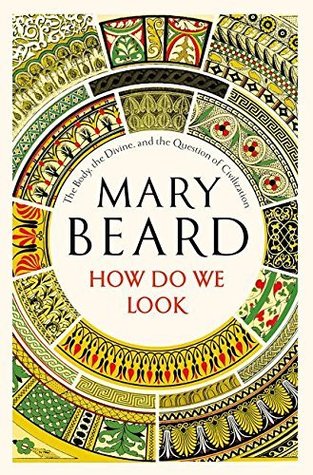

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

The modern idea that the female nude implies the existence of a predatory male gaze was not first thought up, as is often imagined, in the feminism of the 1960s.

what is believed to be the very first life-sized statue of a female nude in classical Greece – a fourth-century BCE image of the goddess Aphrodite – provoked exactly the same kind of debate.

(for much of world history the idea of a ‘civilised woman’ has been a contradiction in terms),

And it was all underpinned by an intense investment in the youthful, athletic human body, almost as if that was a physical guarantee of moral and political virtue, or an encouragement to it.

The ideal male citizen was, in the Athenian stereotype, both ‘perfectly formed’ and ‘good’ (kalos kai agathos, as the influential Greek cliché put it).

This was no crude campaign in social instruction, but taken together they were telling the Athenians how to be Athenian. We might compare – whatever the very different contexts – the message of western advertisements in the 1950s and later, suggesting ways of ideal living through the imagery of consumer goods.

this wine cooler pointed to even more difficult issues about where the boundary really lay between civilisation and its absence, between the human and the animal – and to the question of how much wine you had to consume before you really did turn into a beast, and where and how to draw the line between the civilised citizen and those, like the satyrs, whose home was said to be outside the city, in the uncivilised wild. 9.

In fact, when Romans thought about where the impulse to portraiture came from, one of the stories they told was a story of loss: not in this case of death but of poignant absence of another kind.

In his discussion of the origins of different forms of art, he gave a starring role to a young woman who was the creative genius behind one of the earliest portraits. Her lover, it was said, was going away on a long journey and, before he went, she got a lamp, threw his shadow against the wall and traced round it to create his silhouette.

But whatever its precise background, in telling this story, some Romans at least were imagining that portraiture from its very origin was not just a way of remembering or memorialising a person, but a way of actually keeping their presence in our world.

Some 200 years after the reign of Qin, it is reckoned that half the earth’s population lived under the control of either Rome or China, and there are reports of a few puzzled ambassadors travelling between the two capitals (not to mention all kinds of tall stories: Roman writers imagined the Chinese lived to the age of 200; Chinese writers in their turn claimed that Romans rulers lived in palaces with columns made of crystal and that the people were expert jugglers).

The soldiers themselves are made in pieces, with the head slotted in last, and the variety in the facial features is the result of mixing a fairly restricted repertoire of elements: there are only a few different eyebrow types, for example, or different moustache types, put together in different combinations.

They were not dilapidated through natural wear and tear but, soon after the first emperor’s death, they were smashed and burned by rebels against the dynasty who launched a direct attack on his burial place. In that keen desire to destroy them lies the clearest sense of the power of these images.

‘Ozymandias’ (the Greek version of the name Rameses). ‘Two vast and trunkless legs of stone / Stand in the desert …’ he wrote; and nearby, he claimed, was a famous inscription, ‘My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings. / Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!’

There are several uncomfortable lessons inscribed in this story. It is a reminder of how troubling some of the implications of the Greek Revolution could be, how seductive to blur the boundary between life-like marble and real-life flesh, and at the same time how dangerous and foolish. It shows how a female statue can drive a man mad but also how art can act as an alibi for what was – let’s face it – rape. Don’t forget, Aphrodite never consented.

This is not simply a muddle. These apparently confusing paintings, created by generations of now anonymous artists, made their viewers do religious work.

Religion often trades on complexity. Although outside observers and analytic historians may often close their eyes to it, religion exploits the fact that belief can be configured in different ways and that there is always a gap between faith and knowledge. Behind the gorgeous clarity of Herringham’s copies, that is exactly what we see inside the Ajanta caves: complexity converted into paint.

The mosaics at San Vitale together add up to a very strong case for the divine status of Jesus, as if to erode any misunderstanding. He appears as part of a calculated scheme of images, almost designed to end the controversy, guiding the viewer to the ‘right’ conclusion. At the east end of the church, in perfect alignment, are images which present three different aspects of Jesus. In the apse there is the young beardless Jesus, the son of God. At the centre of the ceiling is Jesus as the symbolic lamb of God. At the top of the entrance arch is the older, bearded, all-powerful Jesus, as

...more

Writing is not always intended to be read; it can work in other ways too, more symbolic than practical. Islamic calligraphy is nothing less than an attempt to represent the divine in visual form, but not as human. It puts God on display as his word; it is God seen in the art of writing.

words are ‘a form of blessing and just by looking at it you can absorb some of the blessing’.

calligraphy evolved to redefine what an image of God could be, transforming the word into the image.

sculpture on almost every place on the building you could possibly fit it. Not all the Athenians at the time were as impressed with this as we are. Some claimed that it was all too extravagant, part of a project to dress up Athens like a whore. Others joked about the families of mice that made their homes up the skirts of statues like the Athena Parthenos (whose gold and ivory construction was not solid, but built around a frame much like that under the clothing of the Virgin Mary in Seville).

So if you ask me what is civilisation, I say it’s little more than an act of faith.