More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

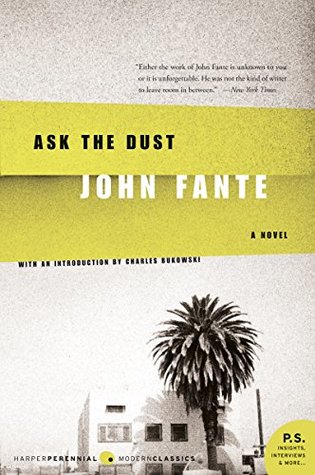

by

John Fante

Read between

February 7 - February 9, 2025

the little girl

read my story with a soft sweet voice that had me weeping at the first hundred words. It was like a dream, the voice of an angel filling the room, and in a little while she was sobbing too, interrupting her reading now and then with gulps and chokes, and protesting. “I can’t read anymore,”

“But you’ve got to, Judy. Oh, ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

tall, bitter-mouthed woman suddenly entered the room without kno...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Judy’s m...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

She had come and gone as quickly as that, and I never saw her again. It was a mystery to the landlady too, for they had arrived and departed that very day, not even staying over night.

There was a letter from Hackmuth in my box. I

he replied in one small paragraph. But that was fine in its way, because his replies were easier to memorize and know by heart. He had a way, that Hackmuth; he had a style; he had so much to give, even his commas and semi-colons had a way of dancing up and down. I used to tear the stamps off his envelopes, peel them off gently, to see what was under them. I sat on the bed and opened

Mr. Bandini, With your permission I shall remove the salutation and ending of your long letter and print it as a short story for my magazine. It seems to me you have done a fine job here. I think “The Long Lost Hills” would serve as an excellent title. My check is enclosed. Sincerely yours, J. C. Hackmuth.

Oh God, Hackmuth! How can you he such a wonderful man? How is it possible? I climbed back to my room and found the check inside the envelope.

was $175. I was a rich man once more. $175! Arturo Bandini, author of The Little Dog Laughed and The Long Lost Hills.

And as for you, Camilla Lopez, I want to see you

tonight. I want to talk to you, Camilla Lopez. And I warn you, Camilla Lopez, remember that you stand before none other than Arturo Bandini, the writer.

The May Company basement. It was the finest suit of clothes I ever bought, a brown pin-stripe with two

of pants. Now I could be well dressed at all times. I bought two-tone brown and white shoes, a lot of shirts and a lot of socks, and a hat.

bought a pair of sunglasses. I spent the rest of the afternoon buying things, killing time. I bought cigarets, candy and candied fruit. I bought two reams of expensive paper, rubber bands, paper clips, note pads, a small filing cabinet, and a gadget for punching holes in paper.

cheap watch, a bed lamp, a comb, toothbrushes, tooth paste, hair lotion, shaving cream, skin lotion, and a first aid kit. I stopped at a tie shop and bought ties, a new belt, a watch chain, handkerchiefs, bathrobe and bedroom slippers.

didn’t like the change either. All at once everything began to irritate me. The stiff collar was strangling me. The shoes pinched my feet. The pants smelled like a clothing store basement and were too tight in the crotch. Sweat broke out at my temples where the hat band squeezed my skull. Suddenly I began to itch, and when I moved everything crackled like a paper sack.

Could this hog-tied, strangling buffoon be the creator of The Long Lost Hills? I pulled everything off, washed the smells out of my hair, and climbed into my old clothes. They were very glad to have me again; they clung to me with cool delight, and my tormented feet slipped into the old shoes as into the softness of Spring grass.

“I want a Scotch highball,” I said. “St. James.” She discussed it with the bartender, then came back. “We don’t have St. James. We have Ballantine’s, though. It’s expensive. Forty cents.” I ordered one for myself and one each for the two bartenders. “You shouldn’t spend your money like that,”

“I thought you’d like my new shoes,” she said. I had resumed the reading of Hackmuth’s letter. “They seem all right,” I said. She limped away to a table just vacated and began picking up empty beer mugs. She was hurt, her face long and sad.

“You’ve changed,” she said. “You’re different. I liked you better the other way.”

“Little Mexican princess,” I said. “You’re so charming, so innocent.” She jerked her hand away and her face lost color. “I’m not a Mexican!” she said. “I’m an American.”

“To me you’ll always be a sweet little peon. A flower girl from old Mexico.” “You dago sonofabitch!” she said.

When she returned she moved gracefully, her feet quick and sure. She had taken off the white shoes and put on the old huaraches. “I’m sorry,” she said. “No,” I said. “It’s my fault, Camilla.” “I didn’t mean what I said.”

Her car was a 1929 Ford roadster with horsehair bursting from upholstery,

battered fenders and no top. I sat in it and fooled with the gadgets. I looked at the owner’s certificate. It was made out to Camilla Lombard, not Camilla Lopez.

I asked her about the Camilla Lombard written on her owner’s certificate. I asked her if she was married. “No,” she said. “What’s the Lombard for?” “For fun,” she said. “Sometimes I use it professionally.”

In silence we reached the Palisades, driving along the crest of the high cliffs overlooking the sea. A cold wind sideswiped us. The jalopy teetered. From below rose the roar of the sea.

Below us the breakers flayed the land with white fists. They retreated and came back to flay it again. As each breaker retreated, the shoreline broke into an ever-widening grin. We coasted in second down the spiral road, the black pavement perspiring, fog tongues licking it.

Then I felt myself in the big breakers once more, heard them booming louder.

To breathe was all that mattered. Under water the current rushed, rolling and dragging me. So this was the end of Camilla, and this was the end of Arturo Bandini—but even then I was

writing it all down, seeing it across a page in a typewriter, writing it out and coasting along the sharp sand, so s...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Not fifty feet away Camilla waded toward the land in water to her waist. She was laughing, choking from it, this supreme joke she had played, and when I saw her dive ahead of the next breaker with all the grace and perfection of a seal,

We reached the city. I told her where I lived. “Bunker Hill?” She laughed. “It’s a good place for you.” “It’s perfect,” I said. “In my hotel they don’t allow Mexicans.”

As I closed the door all the desire that had not come a while before seized me. It pounded my skull and tingled in my fingers. I threw myself on the bed and tore the pillow with my hands.

Here and there were evidences of the quake; a tumbled brick wall, a fallen chimney. Los Angeles was doomed. It was a city with a curse upon it. This particular earthquake had not destroyed it, but any day now another would raze it to the ground. They wouldn’t get me, they’d never catch me inside a brick building.

The world was dust, and dust it would become. I began going to Mass

in the mornings. I went to Confession. I received Holy Communion. I picked out a little frame church, squat and solid, down near the Mexican quarter.

Ah life! Thou sweet bitter tragedy, thou dazzling whore that leade...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

What doth it profit a man if he gain the whole world and suffer the loss of his own soul? And

then that little poem: Take all the pleasures of all the spheres, multiply them by endless years, one minute of heaven is worth them all.

And then, like a dream it came. Out of my desperation it came—an idea, my first sound idea, the first in my entire life, full-bodied and clean and strong, line after line, page after page. A story about Vera Rivken.

Camilla! I had to have that Camilla! I got up and walked out of the hotel and down Bunker Hill to the Columbia Buffet.

“Back again?” Like film over my eyes, like a spider web over me. “Why not?”

“Please, Camilla. Just tonight. It’s so important.” “I can’t, Arturo. Really, I can’t. “You’ll see me,” I said. She walked away. I pushed back my chair. I pointed my finger at her, yelled it out: “You’ll see me! You little insolent beerhall twirp! You’ll see me!”

She screamed, charged me. I caught her in my arms and pinned her elbows down. She kicked and tried to scratch my legs. Sammy watched with disgust. Sure I was disgusting, but that was my affair. She cried and fought, but she was helpless, her legs dangling, her arms held tight. Then she tired a little, and I released her. She straightened her dress, her teeth chattering her hatred.

This interested me. A new side to my character, the bestial, the darkness, the unplumbed depth of a new Bandini.

said I was through with Camilla Lopez forever. And you’ll regret it, you little fool, because I’m going to be famous. I sat before my typewriter and worked most of the night.

Sammy: That little whore was here tonight; you know, Sammy, the little Greaser dame with a wonderful figure and a mind for a moron. She presented me with certain alleged writings purportedly written by yourself. Furthermore she stated the man with the scythe is about to mow