More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

January 25 - February 9, 2021

Lolita, when published, was infamous, then famous, always controversial, always a topic of discussion. It has sold more than sixty million copies worldwide in its sixty-plus years of life. Sally Horner, however, was largely forgotten, except by her immediate family members and close friends. They would not even learn of the connection to Lolita until just a few years ago. A curious reporter had drawn a line between the real girl and the fictional character in the early 1960s, only to be scoffed at by the Nabokovs. Then, around the novel’s fiftieth anniversary, a well-versed Nabokov scholar

...more

It was my habit then, and remains so now, to plumb obscure corners of the Internet for ideas. I gravitate toward the mid-twentieth century because that period is well documented by newspapers, radio, even early television, yet just outside the bounds of memory. Court records still exist, but require extra rounds of effort to uncover. There are people still alive who remember what happened, but few enough that their recollections are on the cusp of vanishing. Here, in that liminal space where the contemporary meets the past, are stories crying out for greater context and understanding. Sally

...more

Even after chasing down court documents, talking to family members, visiting some of the places she had lived—and some of the places where La Salle took her—and writing the piece, I knew I wasn’t finished with Sally Horner. Or, more accurately, she was not finished with me. What drove me then and galls me now is that Sally’s abduction defined her entire short life. She never had a chance to grow up, pursue a career, marry, have children, grow old, be happy. She never got to build on the fierce intelligence so evident to her best friend that, nearly seven decades later, she spoke to me of Sally

...more

Like Lolita, Sally Horner was no “little deadly demon among the wholesome children.” Both girls, fictional and real, were wholesome children. Contrary to Humbert Humbert’s assertions, Sally, like Lolita, was no seductress, “unconscious herself of her fantastic power.” The fantastic power both girls possessed was the capacity to haunt.

Those iconic opening lines, “Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins. My sin, my soul. Lo-lee-ta,” sent a frisson down my adolescent spine. I didn’t like that feeling, but I wasn’t supposed to. I was soon in thrall to Humbert Humbert’s voice, the silken veneer barely concealing a loathsome predilection. I kept reading, hoping there might be some salvation for Dolores, even though I should have known from the foreword, supplied by the fictional narrator John Ray, Jr., PhD, that it does not arrive for a long time. And when she finally escapes from Humbert’s clutches to embrace her own life,

...more

It is all too easy to be seduced by his sophisticated narration, his panoramic descriptions of America, circa 1947, and his observations of the girl he nicknames Lolita. Those who love language and literature are rewarded richly, but also duped. If you’re not being careful, you lose sight of the fact that Humbert raped a twelve-year-old child repeatedly over the course of nearly two years, and got away with it.

Mikita Brottman, who in The Maximum Security Book Club described her own cognitive dissonance discussing Lolita with the discussion group she led at a Maryland maximum-security prison. Brottman, reading the novel in advance, had “immediately fallen in love with the narrator,” so much so that Humbert Humbert’s “style, humor, and sophistication blind[ed] me to his faults.” Brottman knew she shouldn’t sympathize with a pedophile, but she couldn’t help being mesmerized. The prisoners in her book club were nowhere near so enchanted. An hour into the discussion, one of them looked up at Brottman and

...more

Millions of readers missed how Lolita folded in the story of a girl who experienced in real life what Dolores Haze suffered on the page. The appreciation of art can make a sucker out of those who forget the darkness of real life. Knowing about Sally Horner does not diminish Lolita’s brilliance, or Nabokov’s audacious inventiveness, but it does augment the horror he also captured in the novel.

He made his public distaste for the literal mapping of fiction to real life known as early as 1944, in his idiosyncratic, highly selective, and sharply critical biography of the Russian writer Nikolai Gogol. “It is strange, the morbid inclination we have to derive satisfaction from the fact (generally false and always irrelevant) that a work of art is traceable to a ‘true story,’” Nabokov chided. “Is it because we begin to respect ourselves more when we learn that the writer, just like ourselves, was not clever enough to make up a story himself?”

With respect to his own work, Nabokov did not want critics, academics, students, and readers to look for literal meanings or real-life influences. Whatever source material he’d relied on was grist for his own literary mill, to be used as only he saw fit. His insistence on the utter command of his craft served Nabokov well as his reputation and fame grew after the American publication of Lolita in 1958. Scores of interviewers, whether they wrote him letters, interrogated him on television, or visited him at his house, abided by his rules of engagement. They handed over their questions in

...more

After he immigrated to the United States in 1940, Nabokov also abandoned Russian, the language of the first half of his literary career, for English. He equated losing his mother tongue to losing a limb, even though, in terms of style and syntax, his English dazzled beyond the imagination of most native speakers.

We’ve also learned more about what made Nabokov tick since the Library of Congress lifted its fifty-year restriction upon his papers in 2009, opening the entire collection to the public. The more substantive trove at the New York Public Library’s Berg Collection still has some restrictions, but I was able to immerse myself in Nabokov’s work, his notes, his manuscripts, and also the ephemera—newspaper clippings, letters, photographs, diaries. A strange thing happened as I looked for clues in his published work and his archives: Nabokov grew less knowable.

What helped me grapple with the book was to reread it, again and again. Sometimes like a potboiler, in a single gulp, and other times slowing down to cross-check each sentence. No one could get every reference and recursion on the first try; the novel rewards repeated reading. Nabokov himself believed the only novels worth reading are the ones that demand to be read on multiple occasions. Once you grasp it, the contradictions of Lolita’s narrative and plot structure reveal a logic true to itself.

“Personally, I never could understand the good of thinking up books, of penning things that had not really happened in some way or other . . . were I a writer, I should allow only my heart to have imagination, and for the rest to rely upon memory, that long-drawn sunset shadow of one’s personal truth.” Nabokov himself never openly admitted to such an attitude himself. But the clues are all there in his work. Particularly so in Lolita, with its careful attention to popular culture, the habits of preadolescent girls, and the banalities of then-modern American life. Searching out these signs of

...more

The case for what Vladimir Nabokov knew of Sally Horner and when he knew it falls squarely into the latter category. Investigating it, and how he incorporated Sally’s story into Lolita, led me to uncover deeper ties between reality and fiction, and to the thematic compulsion Nabokov spent more than two decades exploring, in fits and starts, before finding full fruition in Lolita. Lolita’s narrative, it turns out, depended more on a real-life crime than Nabokov would ever admit.

Highlights will end soon.

But this book is asking good questions.

(Note: Too many helpful passages. A lot of highlights ahead.)

I would argue that even casual readers of Lolita, who number in the tens of millions, plus the many more millions with some awareness of the novel, the two film versions, or its place in the culture these past six decades, should pay attention to the story of Sally Horner because it is the story of so many girls and women, not just in America, but everywhere. So many of these stories seem like everyday injustices—young women denied opportunity to advance, tethered to marriage and motherhood. Others are more horrific, girls and women abused, brutalized, kidnapped, or worse. Yet Sally Horner’s

...more

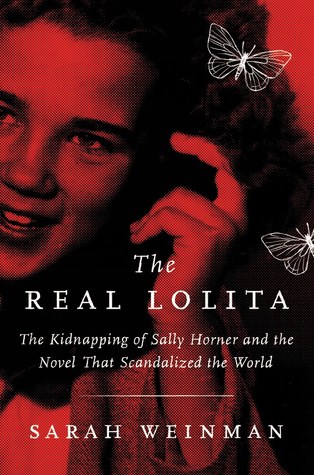

Vladimir Nabokov, through his use of language and formal invention, gave fictional authority to a pedophile and charmed and revolted millions of readers in the process. By exploring the life of Sally Horner, I reveal the truth behind the curtain of fiction. What Humbert Humbert did to Dolores Haze is, in fact, what Frank La Salle did to Sally Horner in 1948. With this book, Sally Horner takes precedence. Like the butterflies that Vladimir Nabokov so loved, she emerges from the cage of both fiction and fact, ready to fly free.

Humbert Humbert was describing a compulsion. Vladimir Nabokov set out to create an archetype. But the real little girls who fit this idea of the mythical nymphet end up getting lost in the need for artistic license. The abuse that Sally Horner, and other girls like her, endured should not be subsumed by dazzling prose, no matter how brilliant.

I think the artistry on display in the novel is defensible but deeply problematic.

I think Kubrick, men and women who refuse to find Humbert the fucking worst person imaginable do real harm to victims of predatory violence against kids.

A lot of fucked up things here to unpack. The novel brings a bunch of things to the table to start a good conversation. Better source materials exist now, but who is to say this discussion even exists without ‘Lolita’ being ‘Lolita’.

Yet there is no direct proof that Vladimir Nabokov learned of Sally Horner’s abduction and rescue in March 1950. There was no story in the papers he was most likely to read—the Cornell Daily Sun, the college newspaper, or the New York Times. Similarly, there’s no direct proof he glanced at the Camden or Philadelphia papers, the ones that carried the best details and the most vivid photos. Neither his archives at the New York Public Library nor those at the Library of Congress contain newspaper clippings about Sally. Any connection dances just outside the frame. However, there is plenty of

...more

“Only the other day we read in the newspapers some bunkum about a middle-aged morals offender who pleaded guilty to the violation of the Mann Act and to transporting a nine-year-old girl across state lines for immoral purposes, whatever they are. Dolores darling! You are not nine but almost thirteen, and I would not advise you to consider yourself my cross-country slave. . . . I am your father, and I am speaking English, and I love you.” As Nabokov scholar Alexander Dolinin pointed out in his 2005 essay linking Sally Horner to Lolita, Nabokov fiddled with the case chronology. The cross-country

...more

She’d had trouble making friends before her abduction; afterward it became even more difficult. Classmates whispered and gossiped about her time with La Salle. Boys, emboldened and entitled, peppered her with unwanted remarks and propositions. As her classmate Carol Taylor—née Carol Starts—remembered, “they looked at her as a total whore.” Emma DiRenzo, whom Sally knew as Emma Annibale, agreed. “She had a little bit of a rough time at first. Not everyone was very nice. I think some people didn’t believe her.” It didn’t matter to Sally’s classmates that she had been abducted and raped. That she

...more

Vladimir Nabokov opened up a newspaper somewhere near Afton, Wyoming, and chanced upon an Associated Press story. Perhaps the newspaper Nabokov read was the New York Times, which carried the wire report of Sally Horner’s death on page twelve of their early edition. Maybe it was a local daily, which splashed the sensational news on or near the front page. Wherever Nabokov read the report, he took notes on one of his ninety-four surviving Lolita index cards. The handwritten card reads as follows: 20.viii.52 Woodbine, N.J. – Sally Horner, 15-year-old Camden, N.J. Girl who spent 21 months as the

...more

Dolinin takes a charitable view of Nabokov’s treatment of Sally Horner in Lolita, claiming that the number of references, including the architecture of the novel’s second half, does not obscure the real girl. Rather, he writes, “[Nabokov] wanted us to remember and pity the poor girl whose stolen childhood and untimely death helped to give birth to his (not Humbert Humbert’s) Lolita—the genuine heroine of the novel hidden behind the narrator’s self-indulgent verbosity.” This sense of pity Dolinin speaks of emerges in Humbert’s final meeting with Dolores. She is married, pregnant, and seventeen,

...more

“. . . in the infinite run it does not matter a jot that a North American girl-child named Dolores Haze had been deprived of her childhood by a maniac, unless this can be proven (and if it can, then life is a joke), I see nothing for the treatment of my misery but the melancholy . . . palliative of articulate art.” Humbert’s epiphany is in keeping with Véra’s diary note only days after the American publication of Lolita in 1958. She was ecstatic about the largely positive press and fast sales of the novel, but was unnerved by what critics weren’t saying. “I wish, though, somebody would notice

...more

She excels at tennis; she is free with sharp comebacks (“You talk like a book, Dad”); and when she seizes the opportunity to break away from Humbert and run off with Clare Quilty, she does so in order to survive. Any fate is better than staying with her stepfather. Never mind that she will, later, run from Quilty’s desire to embroil her in pornography with multiple people. Never mind that Dolores will “settle” for Dick Schiller and a life of domesticity and motherhood that is, sadly, cut short. She still has the freedom and the autonomy to make these choices for herself, a freedom she never

...more

While the transcript of the proceeding is lost, I discovered the outcome of La Salle’s habeas hearing in a motion filed after the fact by Camden County prosecutor Mitchell Cohen: La Salle perjured himself on the stand by denying he had pleaded guilty to the abduction and kidnapping charges when, in fact, he made that plea in open court in April 1950. Future New Jersey governor and chief justice of the State Supreme Court Richard Hughes presided over the case as a county court judge. Hughes was so incensed by La Salle’s lies on the stand that he told the prisoner: “I hardly think you should be

...more

La Salle attested, time and again, to having “sworn proof” that Sally was his daughter, but of course he could never deliver the goods. He even reproved the media for publishing Sally’s name after she was rescued in San Jose on the grounds of “a statute against such publicity for a child.” He claimed his quick guilty plea resulted from being afraid of “MOB VIOLENCE” (the capitalization is La Salle’s) and also claimed that the prosecutor, Cohen, “told the defendant there was no use of his trying to get an attorney as no attorney could do any good.”

Ruth clung to her role in Sally’s rescue for the rest of her life, and brought it up again and again to her children. She wanted them to believe in her as a heroine. She wanted them to know she was capable of a decent act. Some of her sons and daughters never reconciled Ruth’s contradictions. Rachel, however, finally came to believe that her mother “did the best she knew how,” no matter how many grievous mistakes she made as a mother and a human being.

“When I looked at him, I could see a lot of myself in his face,” Madeline said. “My husband picked it up right away.” For those last months, Madeline did not clutter her relationship with questions of what La Salle had done to land him in prison. “We talked as father and daughter would talk,” Madeline told me. “There wasn’t a strain. He was just Dad. Truth be told, I never thought about whether he was guilty or not guilty.” Just as John Ray, Jr., became the conduit for Humbert Humbert’s so-called confession, Madeline, unwittingly, became the keeper of Frank La Salle’s version of the story.

...more

The Grammer case clearly echoed the untimely death of Charlotte Haze, struck by a car after running away from the argument with Humbert where she learns of his true designs on her daughter. The final line of the Grammer paragraph in Lolita reads with further chilling force. Grammer could not conceal his crime from the world after all. Humbert Humbert, systematically raping Dolores Haze for nearly two years on a cross-country odyssey, could, and did. No wonder he concluded: “I did better.” I bring up the Grammer case because it is another concrete example of Vladimir Nabokov drawing upon

...more

THE NABOKOVS WOULD VENTURE WEST one more time before Vladimir finished the Lolita manuscript. After so many years of work—five or six, depending on who was counting and who was listening—Lolita was nearly done, despite not being anywhere close to publication. This road trip also proved to be the longest Vladimir and Véra stayed away from the East Coast. They left Ithaca in that still-reliable Oldsmobile in early April 1953. From there they headed toward Birmingham, Alabama, a pit stop en route to the Chiricahua Mountains in Arizona, where butterflies were supposed to be plentiful. What Nabokov

...more

When there were no butterflies to catalog, Nabokov was on a mad sprint to finish Lolita, burning his handwritten pages as soon as Véra typed them up. When their Oregon summer idyll ended, the Nabokovs wended their way back east via Jenny Lake and the Grand Tetons.

On December 6, 1953, Vladimir Nabokov wrote a note in his diary, at the bottom of a page largely filled with numerical grades for the final assignment of his literature class. “Finished Lolita which was begun exactly 5 years ago.” It was a finish line he’d spent many of those years never expecting to reach. There were classes to teach at Cornell to pay the bills and to fund his summer trips to hunt butterflies. Other projects had also interrupted Nabokov’s progress on Lolita, from translation work (The Song of Igor’s Campaign) to the first version of his autobiography, which was published in

...more

Nabokov had spent the summer of 1953 trip writing steadily, almost maniacally, dictating his prose to Véra, then “crumpling each old manuscript sheet once it had served its turn and discarding the pages out the car window or into a hotel fireplace.” Nabokov put in sixteen-hour writing days over the course of the fall of 1953—on Cornell’s dime—delegating the teaching and exam-marking to Véra.

In a September 29, 1953, letter to Katharine White at the New Yorker, Nabokov called the book an “enormous, mysterious, heartbreaking novel that, after five years of monstrous misgivings and diabolical labors, I have more or less completed.”

Lolita was ready to be submitted to publishers, but there was a catch: Nabokov refused to put his own name to the novel. He asked Katharine White, in the same letter in which he solicited her feedback, whether book publishers would go along with his request. She replied that “from her experience, an author’s identity sooner or later leaked out.” Still, Nabokov wanted to keep his identity secret, for the same reasons that spurred him to burn the manuscript pages of Lolita as he finished them. He believed being publicly associated with such an incendiary book might imperil both his literary and

...more

Nabokov’s editor at Viking, Pascal Covici, rejected the manuscript. So, too, did James Laughlin, the New Directions publisher whom Nabokov worked with on The Real Life of Sebastian Knight, Laughter in the Dark, and Nikolai Gogol. Farrar, Straus and Simon & Schuster also came back with the same verdict: they didn’t believe they could publish because it would be too expensive to defend in court on possible obscenity charges. Jason Epstein at Doubleday did want to publish, but the company president, once he got wind of what Lolita was about, overruled him. The manuscript also detoured away from

...more

The last of the rejections by American book firms arrived in February 1955. To publish Lolita, Nabokov had to look outside of America, and beyond highbrow intellectual circles. Nabokov joked to Edmund Wilson several weeks later: “I suppose it will be finally published by some shady firm with a Viennese-Dream name.” The joke became truth before the summer of 1955 was over.

MAURICE GIRODIAS was the founder and publisher of Olympia Press, best known for publishing books others wouldn’t touch. Most of those books were, in fact, smut—badly written, hastily produced. Others got that label affixed to them, like Henry Miller’s Tropic of Capricorn and Tropic of Cancer, J. P. Donleavy’s The Ginger Man, and the pseudonymous The Story of O (revealed, decades later, to be the work of Anne Desclos). Nabokov’s Europe-based agent, Doussia Ergaz, submitted Lolita to Girodias because of his work as an art-book publisher. She didn’t seem to know much about the seedier side of

...more

That relief dissipated quickly, once he realized the contract he’d signed on June 6, 1955, better resembled a devil’s bargain. Nabokov’s new publisher had mistaken the author for his creation, thinking Nabokov drew upon some perverse experience. Girodias also insisted the novel be published under Nabokov’s name, and Nabokov did not feel he had the leverage to object, when the alternate option was no publication at all. Nabokov also did not see galley proofs until it was too late to make changes, which vexed a man known for his fastidiousness to no end. Olympia Press published Lolita on

...more

As Nabokov later recalled, “From the very start I was confronted with the peculiar aura surrounding [Girodias’s] business transactions with me, an aura of negligence, evasiveness, procrastination, and falsity.”

Nabokov saw no money from Lolita over the first two years of publication, despite strong sales in France. In October 1957, he had finally had enough of Girodias’s prevarications and shady dealings, telling him the deal was off and that as a result, all rights reverted back to him. Girodias paid what was owed (44,220 “anciens francs”), and Nabokov let the matter go. Girodias, however, soon reverted back to his nonpayment ways, and Nabokov’s irritation increased.

ON AUGUST 30, 1957, Nabokov received a letter from Walter Minton, president and publisher of G. P. Putnam’s Sons. “Being a rather backward example of that rather backward species, the American publisher, it was only recently that I began to hear about a book called Lolita,” Minton wrote. After some more preamble, he got to the point: “I am wondering if the book is available for publication.”

Minton, in turn, discovered the pages at her Upper East Side apartment. “I woke in the middle of the night and there was this story on the table. I started reading,” he recalled in early 2018, sixty years later. “By morning, I knew I had to publish it.” (Ridgewell was in line for a tidy payday for her literary scouting efforts, per a standing Putnam policy: the equivalent of 10 percent of an author’s royalties for the first year, plus 10 percent of the publisher’s share of subsidiary rights for two years.)

Now it irked him that Girodias might be in line for a significant payout when he had been so slow with the initial Lolita royalties, and then did not bother to pay further monies Nabokov was owed. In the two years since Lolita first appeared in book form, he was desperate to reap the financial rewards—as well as to get the critical attention he deserved.

All manner of people benefited from Lolita, whether to praise or denounce it, but Vladimir Nabokov had hardly earned a dime for his years of creative labor.