More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

February 17, 2018 - June 7, 2019

Bradford to the east, Halifax to the south and Burnley to the west,

Those inhabitants who were not directly employed in the mills were involved in various trades, most of them connected with wool. As at Thornton and Hartshead, there were large numbers of hand-loom weavers working in their own homes but there was also a very substantial cottage industry of wool-combing.

Haworth was therefore in the unusual position of being able to run its own worsted trade from start to finish.

the whole sweep of moorland between Heptonstall, Keighley and his old chapelry of Thornton.

To those who love bleak and dramatic scenery there is something almost heart-wrenching in the beauty of the sweep of moorlands round Haworth.

Apart from a few short weeks in September, when the moors are covered with the purple bloom of the heather and the air is heavy with its scent, the predominant colours of the landscape are an infinite variety of subtle shades of brown, green and grey.

The whole landscape is in thrall to the sky, which is rarely cloudless and constantly changing;

there is always a wind at Haworth;

Much of the scenery remains as it was in the Brontës’ day, but the insatiable greed of the twenty-first century is swallowing it up at a frightening pace.

giant wind turbines stalk the horizons,

Tucked away in the valley bottom are some of the mills on which the local economy depended: Ebor Mill, owned for many generations by the Merrall family, and the vast complex of Bridgehouse Mills. Just above the latter and set well back from the road in several acres of grounds, now considerably reduced by new

building, stands Woodlands, perhaps the most gracious mill owner’s house in early nineteenth-century Haworth. It had a chequered history, changing hands according to the fortunes of trade.15

At the junction itself the large, stone-built Hall Green Baptist Chapel, built in 1824, stands facing Haworth Old Hall, a seventeenth-century manor house which was divided into tenements in the Brontës’ day.

Sun Street is little changed, its cottages petering out as the road climbs along and up the hill, past the old Haworth Grammar

School, to Marsh and Oxenhope.

The water was tainted by the overflow from the midden-steads, which every house with access

At the top of Main Street the road widens and divides into West Lane and Changegate.

At the foot of the church steps is the Black Bull, notorious as the supposed haunt of Branwell Brontë,

only the tower, with the addition of an extra few feet above the second window to take the clock, remains from the original church.25

The dominance of the pulpit, rather than the altar, in the arrangement of the church reflected the fact that, at that time, the sermon was the central part of the service and communion was taken much less frequently than it is today.

The church, dedicated to St Michael and All Angels, was only a stone’s throw from the National Church Sunday School which Patrick had built, and which still stands on the other side of Church Lane, facing the churchyard. The schoolroom was a low, small, single-storey building, with a bell

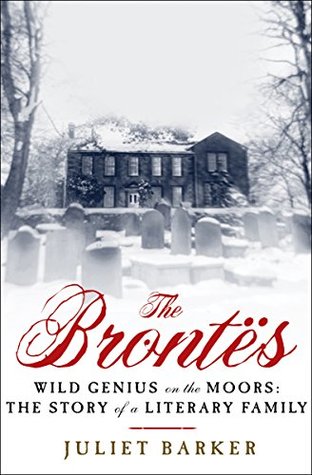

At the top end of Church Lane, the highest point in the village itself, stands the parsonage.

In 1820 the parsonage was virtually the last house in the village; it faced down into Haworth but at the back it looked over the miles of

open moorland where Yorkshire meets Lancashire.

Brow Moor, Oakworth Moor and Steeton Moor.

from their vantage point at the parsonage, the Brontës would have looked not down at the churchyard but across and up to the sweep of moorland hills stretching as far as the Yorkshire Dales:

‘The wind goes

piping and wailing and sobbing round the square unsheltered house in a very strange unearthly way.’

Everything about the place tells of the most dainty order, the most exquisite cleanliness.

their servants, Tabitha Aykroyd and Martha Brown,

Ellen Nussey, visiting Haworth for the first time some twenty years earlier,

Scant and bare indeed many will say, yet it was not a scantness that made itself felt—

April 1820.

large garden where the children could play safely, well away from a busy main thoroughfare.

The high birth rate in the chapelry was matched by a high mortality rate:

Nevertheless, Patrick made it clear, right from the start of his ministry at Haworth, that he cared deeply about the plight of his parishioners and that he would be active on their behalf.

Elizabeth Firth and her father

29 January, Maria, his wife, was suddenly taken dangerously ill.

‘During every week and almost every day’ of the seven and a half months it took her to die.

Elizabeth Firth came over several times to visit the stricken household.

On 9 February she found Maria ‘very poorly’ so she came again on 21 February and in March.

Scarlet fever was then a mortal sickness, so death threatened not only his wife but all six of his children.

All the children recovered, Maria’s condition improved slightly and a few weeks later, her sister, Elizabeth Branwell, arrived from Penzance to help.

Elizabeth’s presence ‘afforded great comfort to my mind, which has been the case ever since, by sharing my labours and sorrows, and behaving as an affectionate mother to my children’.

and after above seven months of more agonizing pain than I ever saw anyone endure, she fell asleep in Jesus, and her soul took its flight to the mansions of glory.

For two weeks Patrick was prostrate with grief and unable to perform his duties.

William Morgan, who, in happier times, had married Patrick and Maria and christened four of their six children,

Maria was buried in the vault near the altar under Haworth Church.

Patrick’s first encounter with Miss Currer, of Eshton Hall,

William Tetley, the Bradford parish clerk,