More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

January 11 - January 12, 2020

Physical violence by school authorities is typically just one layer experienced by girls; it is compounded by violence at home and in so-called justice systems, and by emotional violence as well.

The day after Beyoncé performed “Formation” at the Super Bowl, Mankaprr arrived in class and offered a serious critique of the Black women’s anthem as inherently flawed. She was prepared to argue her points and did not have a mind to back down. The other students in the room were treated to a fiery intellectual exchange between us.

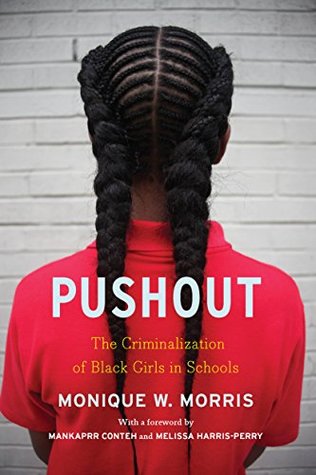

In Pushout Dr. Morris traces how zero-tolerance policies, explicit and implicit biases, and the intersections of racism and sexism create systems where Black girls are suspended, criminalized, and herded into juvenile confinement where they receive disproportionately harsh sentences. Most often, these systems ensnare Black girls in the wake of severe emotional and sexual trauma, confining their unique potential.

Compare that moment to the president’s silence in others. Although he is the father of two girls, he made no public statement or acknowledgment in October 2015, when a South Carolina school resource officer flipped a young girl in foster care from her desk for supposedly being disruptive in class.

Teachers can be healers. And so can other influential adults who shape the trajectories of young people. When Black girl energy is uncontainable, we can jump up and dance with

Black girls are also directly impacted by criminalizing policies and practices that render them vulnerable to abuse, exploitation, dehumanization, and, under the worst circumstances, death.

Not only had she just watched her little brother die at the hands of these officers, but she was forced to grieve his death from the backseat of a police car.

These are mostly girls of color (a disproportionately high percentage of girls are Black and/or Latina), and many of them (by some estimates 40 percent) identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning (LGBTQ), or gender-nonconforming.4

Black girls are 16 percent of the female student population, but nearly one-third of all girls referred to law enforcement and more than one-third of all female school-based arrests.

In May 2013, Ashlynn Avery, a sixteen-year-old diabetic girl in Alabama, fell asleep while reading Huckleberry Finn during her in-school suspension. When she did not respond, the suspension supervisor allegedly threw a book at her and ordered her to leave the classroom.

The implementation of zero-tolerance policies, as I will discuss throughout this book, has become the primary driver of an unscrupulous school-based reliance on law enforcement and school security guards. People who often know little to nothing about child or adolescent development, and who often lack the appropriate awareness and training for the school environments they patrol, are responding to behaviors that were previously managed by skilled teachers, counselors, principals, and other professionals.

In her testimony, she was asked about a beating that she and her husband endured one night from a group of men who identified as Ku Klux Klan members: “They said we should not have any schools . . . They went to a colored man there, whose son had been teaching school, and they took every book they had and threw them into

As Patricia Hill-Collins wrote, “All women engage an ideology that deems middle-class, heterosexual, White femininity as normative. In this context, Black femininity as a subordinated gender identity becomes constructed not just in relation to White women, but also in relation to multiple others, namely, all men, sexual outlaws (prostitutes and lesbians), unmarried women, and girls.”24

In a 2012 report, Race, Gender, and the “School to Prison Pipeline”: Expanding Our Discussion to Include Black Girls,25 I argued that the “pipeline” framework has been largely developed from the conditions and experiences of males.

Through stories we find that Black girls are greatly affected by the stigma of having to participate in identity politics that marginalize them or place them into polarizing categories: they are either “good” girls or “ghetto” girls who behave in ways that exacerbate stereotypes about Black femininity, particularly those relating to socioeconomic status, crime, and punishment.

Broadening the scope to include detention centers, house arrest, electronic monitoring, and other forms of social exclusion allows us to see Black girls in trouble where they might otherwise be hidden.

dental dams

and ultimately to decreasing the institutional and individual risks that fuel mass incarceration and our collective overreliance on punishment.

In her book Between Good and Ghetto: African American Girls and Inner-City Violence, Nikki Jones poses the following question: Why is it that inner-city girls must struggle so hard simply to survive?

Twenty-five percent of Black women live in poverty.6 The unemployment rate for Black women age twenty and over at the end of 2014 was 8.2 percent, compared to 4.4 percent for White women and 5 percent for all women.

These are struggles that many Black women have felt since their girlhood. Forty percent of Black children live in poverty, compared with 23 percent of all children nationwide.10 For Black girls under the age of eighteen, the poverty rate is 35 percent.11 Black girls drop out of school at a rate of 7 percent, compared to 3.8 percent of White girls.12 At 18.9 percent, Black girls have the highest case rate of “person offenses” (e.g., assault, robbery, etc.).13 And they have a higher rate (21.4 percent) of being assigned to residential placement than Latinas (8.3 percent) and White girls (6.8

...more

Claudette Colvin protested the segregation of Montgomery buses by refusing to give up her seat to a White passenger. But most people do not know her name. Why is that? Well, she didn’t fit the profile of a “perfect” protestor. Though Colvin was a member of the Youth Council of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), she was so incensed by the demand to give up her seat that she shouted. She resisted with her body. And she was arrested.

Feminist scholar bell hooks writes and talks of an “oppositional gaze,” a way to examine the presentations of Black feminine identities and confront the paralyzing stereotypes that undermine the well-being of Black women and girls.

But our schools are the places where most of our young people spend their days; they are places that have just as much (arguably more) influence as any other social factor on how children understand themselves personally and in relation to the world around them. Schools are, not surprisingly, one of the largest influences on the life trajectory of Black girls.

She contends that quality teaching includes engaging students in active learning, creating intellectually ambitious tasks, using multiple teaching modalities, assessing student learning and adapting to the learning needs of the students, creating supports, providing clear standards, reflection, and opportunities for revision, and developing a collaborative classroom

Rather than experiencing the alienating effects of education where school-based learning detaches students from their home culture, cultural competence is a way for students to be bicultural and facile in the ability to move between school and home cultures.”

There are in fact culturally relevant curricula, gender-responsive curricula, and trauma-sensitive practices being used in schools across the nation, but not uniformly or prevalently.

Sadly, many schools are dominant structures, sustaining our society’s racial and gender hierarchy.

Remember, there is no hierarchy of oppressions.

Other scholars have parsed the ghetto into tiers, defining the slum ghetto as a “zone of minority-group residential dominance denoted by inadequate housing, high morbidity and infant mortality rates, and related social pathologies.”32

The public school is constantly subject to a judgmental gaze, externally and from within. This is doubly true given the ever-expanding surveillance of Black and Brown children.

Nationwide, about sixteen hundred “dropout factories” are responsible for nearly half of all students who leave high school before earning a diploma and about two-thirds of the students of color who do

They say things like “School’s not for me” or “I was never good at school,” when their performance may actually be impaired by many other factors, including socioeconomic conditions, differential

As such, in the public’s collective consciousness, latent ideas about Black females as hypersexual, conniving, loud, and sassy predominate, even if they make it to college and beyond. Public presentations of these caricatures—via popular memes on social media, in advertising, or in entertainment—prescribe these traits to Black women.

They live with this knowledge in their bodies and subconsciously wrestle with every personal critique of how they navigate their environments.

When asked to describe public school in their own words, girls routinely say that their schools are filled with classrooms and hallways where people “fight” and are disciplined, where security personnel roam the halls, and where they learn about a democracy they don’t experience in school.

perceived their district or community schools as chaotic and disruptive learning spaces in which fighting and arguments were the norm and where adolescents were vying for attention and social status.

Across the country, Black girls have repeatedly described “rowdy” classroom environments that prevent them from being able to focus on learning.

“Usually they’ll say something like, ‘Well, you can stop by for ten or fifteen minutes, but you know, I’m not going to wait after school for an hour or something.’ You know, and it’s like . . . shoot . . . they just did that for the Asian girl . . . There’s a lot of, like, Indian people there, and they’ll stay after school till like five [o’clock], doing extra work or working on an extra project that the teacher gave them to do, and then everybody else will be there for ten or fifteen minutes just to talk.

or why she had a adopted a punishment-or-reward system that presented young women in this classroom with a narrow set of options regarding their supposed rehabilitation.

Internalized racial oppression is “the process by which Black people internalize and accept, not always consciously, the dominant White culture’s oppressive actions and beliefs toward Black people (e.g., negative stereotypes, discrimination, hatred, falsification of historical facts, racist doctrines, White supremacists ideology), while at the same time rejecting the African worldview and cultural motifs.”50 For Black women and girls, internalized racial oppression is also gendered.

Only 62 percent of Black students in the senior class completed their high school graduation requirements. The school’s suspension rate was more than twice that of the district, and its expulsion rate was three times higher than that of the district or the state.

“Why do you think the teachers are scared?” I asked her. “Because sometimes . . . I mean, our parents is like us, you know? Our parents get down just like us. This is how we’re raised. So if we see them come after school, we could easily just beat her up. Somebody could just jump her, even shoot her if it got that serious, you know? Like anybody could see her in her car, see where she live, and follow her home. I mean, it ain’t that hard, you know?”

Black parents who actively talk about school at home may have children who perform better in schools, as opposed to those who just engage directly in the school or simply place a high value on academic achievement, but parental involvement by itself is not a predictor of positive student outcomes.

“They always be like, if some girl call me a bitch, I have to beat her ass, or else they’re going to beat my ass. But then, if I skip school, I’ma get my ass beat. So I’m like, okay, I got to go to school, but if somebody call me something, like a bitch or something, then I got to beat they ass too.”

But it was not okay. To this point, Ladson-Billings wrote, “Although most students were encouraged to write each day, Shannon was regularly permitted to fail. Her refusal to write was not just stubbornness but a ploy to cover up her inability to read, or more specifically, her lack of phonetic awareness.”

Black girls in classrooms across the country have been granted permission to fail by the implicit biases of teachers that lower expectations for them.

Once again, the external is compounded by reflex: internalized, gendered racial oppressions give Black girls permission to lower expectations for themselves.

Pierre Bourdieu and Jean-Claude Passeron note in Reproduction in Society, Education and Culture,

I feel like boys . . . men got more rights than girls, and that shouldn’t be right.”