More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

April 14 - April 26, 2024

Even in high-profile cases involving boys, we often fail to see the girls who were right there alongside them. After the fatal shooting of Tamir Rice, the officers tackled his fourteen-year-old sister to the ground and handcuffed her. Not only had she just watched her little brother die at the hands of these officers, but she was forced to grieve his death from the backseat of a police car.3

· Flag

Nico · Flag

Danielle L

Black girls are 16 percent of the female student population, but nearly one-third of all girls referred to law enforcement and more than one-third of all female school-based arrests.6

And in 2007, Pleajhia Mervin was harmed by a California school security officer after she dropped a piece of cake on the school’s cafeteria floor and refused to pick it up.11

Six-year-old Salecia Johnson was arrested in Georgia in 2012 for having a tantrum in her classroom.

And six-year-old Desre’e Watson was handcuffed and arrested at a Florida school in in 2007 for throwing a tantrum in her kindergarten class.

In Georgia, enslaved Africans or other free people of color were fined or whipped, at the discretion of the court, if discovered reading or writing “in either written or printed characters.”

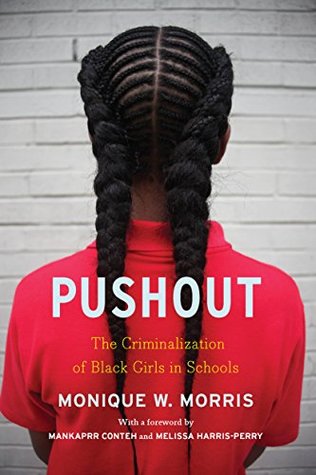

The central argument of this book is that too many Black girls are being criminalized (and physically and mentally harmed) by beliefs, policies, and actions that degrade and marginalize both their learning and their humanity, leading to conditions that push them out of schools and render them vulnerable to even more harm.

Through stories we find that Black girls are greatly affected by the stigma of having to participate in identity politics that marginalize them or place them into polarizing categories: they are either “good” girls or “ghetto” girls who behave in ways that exacerbate stereotypes about Black femininity, particularly those relating to socioeconomic status, crime, and punishment.

Black girls do engage in acts that are deemed “ghetto”—often a euphemism for actions that deviate from social norms tied to a narrow, White middle-class definition of femininity—they are frequently labeled as nonconforming and thereby subjected to criminalizing responses.

For example, a 2007 study found that teachers often perceived Black girls as being “loud, defiant, and precocious” and that Black girls were more likely than their White or Latina peers to be reprimanded for being “unladylike.”

Other research has found that the issuance of summonses and/or arrests appear to be justified by students’ display of “irate,” “insubordinate,” “disrespectful,” “uncooperative,” or “uncontrollable” behavior.

For Black girls, to be “ghetto” represents a certain resilience to how poverty has shaped racial and gender oppression. To be “loud” is a demand to be heard. To have an “attitude” is to reject a doctrine of invisibility and mistreatment. To be flamboyant—or “fabulous”—is to revise the idea that socioeconomic isolation is equated with not having access to materially desirable things. To be a ghetto Black girl, then, is to reinvent what it means to be Black, poor, and female.

Acknowledging the complexity of social identity has been termed “intersectionality,” a concept coined by legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw.21 Her scholarship advances the work of Anna Julia Cooper, Angela Davis, Audre Lorde, and other Black feminist scholars who argued that there is no hierarchy of oppressions.

If schools are teaching curricula that have erased the presence of Black females from the heroic narrative of American exceptionalism (save for a few references during Black History Month in February), are they not implicitly constructing a narrative of exclusion? In a world of normalized exclusion, how and where, then, do Black girls situate themselves as Americans and as global citizens?

Internalized racial oppression is “the process by which Black people internalize and accept, not always consciously, the dominant White culture’s oppressive actions and beliefs toward Black people (e.g., negative stereotypes, discrimination, hatred, falsification of historical facts, racist doctrines, White supremacists ideology), while at the same time rejecting the African worldview and cultural motifs.”50 For Black women and girls, internalized racial oppression is also gendered.

In 2007, six-year-old Desre’e Watson was placed in handcuffs by the Avon Park Police Department for having a bad tantrum in her Florida classroom. According to the police, Desre’e was kicking and scratching, which presented a threat to the safety of others in the school, specifically her classmates and her teacher.

When Desre’e was arrested, she became a symbol of all that was wrong with zero-tolerance policies in the United States. Despite her petite, six-year-old frame, Desre’e was perceived as a threat to public safety. Many were outraged, but most seemed to dismiss it as an isolated incident. Then other incidents began to reach the media.

In 2012, six-year-old Salecia Johnson was arrested in Georgia for throwing books, toys, and wall hangings, amounting to a “tantrum” that was again determined by the school authorities to be an incident worthy of police intervention.

This episode was followed by one in 2013 involving eight-year-old Jmiyha Rickman, an autistic child who suffered from depression and separation anxiety.4 Her hands, feet, and waist were restrained when she was arrested in her Illinois elementary school after throwing a “bad tantrum” and allegedly trying to hit a school resource officer.5 Following her removal from campus, Jmiyha—despite her special needs—was held in the police car for almost two hours.

“Willful defiance” is a widely used, subjective, and arbitrary category for student misbehavior that can include everything from a student having a verbal altercation with a teacher to refusing to remove a hat in school or complete an assignment. It is essentially a formalized way for a school to reprimand students for failing to follow orders. As an undefined catchall category for student misbehavior, willful defiance has been scrutinized for how often it is used to suspend children of color.

In 2014, when California discovered that 43 percent of its suspensions in the 2012-13 academic year were for willful defiance, the state became the nation’s first to limit suspensions tied to this offense.

Zero tolerance results in choices and decisions based on fear and punishment, not personal accountability.

Black students in the Windy City represent 80 percent of Chicago’s multiple out-of-school suspensions, 66 percent of school-related arrests and nearly 62 percent of referrals to law enforcement.38 According to the Consortium on Chicago School Research, the overwhelming majority of these were for offenses that did not pose a “serious threat” to student safety.39

According to the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting Program, White males between the ages of thirteen and eighteen are the most likely to initiate a school-based shooting.48 However, schools in which the student population is largely composed of youth of color have the highest degree of implementing metal detectors, security officers, SROs, and other police forces.

The presence of law enforcement (including school resource officers, school-based probation officers, security officers, and others) has been cited as one of the largest contributing factors to the increased rates of student citations in schools.

Nala was referring to personal items like feminine hygiene products, extra underwear, and/or sports bras. Imagine a young girl’s embarrassment to have to look at a man, or any SRO, after such an inspection—especially if she has a history of sexual victimization.

“They’ll focus on the ones that have it already, whereas if you don’t, they’ll just leave you be,” Michelle said. “When they come at you like you should know it already, it’s like, mmm … should I know it already? You know, you shy away from even opening your mouth.”

For these girls, the ways in which the learning spaces of children were designed to prepare students for a lifetime of institutionalization was shamelessly transparent. However, even in the context of incarceration, people get a “recess”—recreational time, usually outdoors, to take a break. In the absence of a break from the monotony of the day, girls may be less able to pay attention, more irritable and disruptive in class, and less inclined to feel connected to their schoolwork and their classmates.

In September 2013, seven-year-old Tiana Parker was sent home from school in Tulsa, Oklahoma, for wearing dreadlocks. Her small charter school had a dress code, which stated, “Hairstyles such as dreadlocks, afros, mohawks, and other faddish hairstyles are unacceptable.”

A few months later that year, twelve-year-old Vanessa VanDyke in Orlando, Florida, faced expulsion from her parochial school for wearing her hair in a large Afro.

these cases elevated the importance of protecting Black girls from policies that threaten to undermine their ability to learn in good schools simply because of who they are—not for something they have done.

Dress codes in the United States are arbitrary, and in general they are sexist and reinforce the practice of slut shaming. They can also reinforce internalized oppression about the quality of natural hairstyles on people of African descent.

Rules about how they wear their hair and clothes become grounds for punishment, rather than tools to establish a uniform student presentation.

Getting turned away from school for not wearing the “proper” clothing—however that is defined—feels unconscionable in a society that, at least on the surface, declares that education is a priority. This practice is primarily about maintaining a social order that renders girls subject to the approving or disapproving gaze of adults. It is grounded in respectability politics that have very little to do with education and more to do with socialization. So when Black girls respond to this treatment with cries of discrimination, it’s important to see them as disruptors of oppression, not as

...more

A recent report, The Sexual Abuse to Prison Pipeline, highlighted the way in which girls, particularly girls of color, are criminalized as a result of their sexual and physical abuse. Nationwide, girls who are victims of sex trafficking are routinely in contact with the criminal legal system for truancy and placed in detention and/or child welfare facilities.

Children cannot legally consent to sex, which means that when they participate in the sale of sex they are being sexually trafficked and exploited, usually by much older men—and sometimes by women, teenagers, and even society at large (the use of women’s and girls’ bodies to sell other products such as apparel, alcohol, or chewing gum).

Girls of all backgrounds are up against the sexist and dismissive notions that they are choosing a life of prostitution rather than being trafficked into it, though this characterization is significantly more common when it comes to Black girls.

Wearing short shorts on a hot day almost got Deja sent home. The fear, as suggested by the principal’s comment, was that Deja’s shorts might elicit inappropriate touching and behavior among the boys. Instead of focusing on developing a climate in which boys are taught not to touch girls’ bodies, girls are sent home to change their clothes.