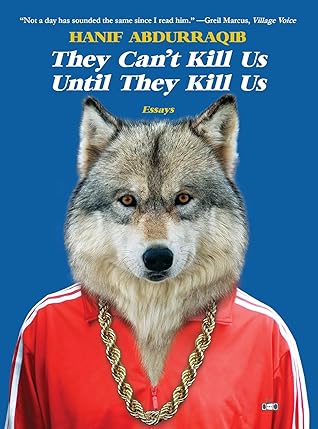

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Because, you see, Hanif Abdurraqib is something between an empath and an illusionist. Among the thousands who have read his work, I am confident that I am not alone when I say that Hanif lured me in with a magic trick—by apparently knowing the textures of my relationship to songs and athletes and places that I love. He knows our secrets. He has an uncanny ability to write about music and the world around it as though he was sitting there on the couch with you in your grandma’s basement, listening to her old vinyl, or he was in that car with you and your high school friend who would later

...more

It is an album of return and escape and return and escape again. It feels, in tone and tension, like coming home for a summer after your first year of college, having tasted another existence and wanting more, but instead sleeping in your childhood room. Home is where the heart begins, but not where the heart stays. The heart scatters across states, and has nothing left after what home takes from it.

At moments in the show, I felt like I was exiting my current body and watching myself from through my younger eyes, wondering if this is what it was always going to come to. Returning to the balm for an old wound, ashamed that I once decided to wear it.

But then, like any good magician, he pivots. Sure, he found the card you chose and that’s impressive, but then you realize he’s turned the whole deck into the queen of hearts and that’s so much more remarkable. And all of a sudden you’re drawn into an irresistible account of some artist whose work you never cared about, maybe someone whose work you even hated or always thought was kinda stupid, or just ignored altogether, and you realize how foolish you’ve been.

We’ve run out of ways to weaponize sadness, and so it becomes an actual weapon. A buffet of sad and bitter songs rains down from the pop charts for years, keeping us tethered to whatever sadness we could dress ourselves in when nothing else fit. Jepsen is trying to unlock the hard door, the one with all of the other feelings behind it.

This is a book about life and death—in particular, though not exclusively, about black life, and black death.

You will believe that I once wore bagg y jeans that dragged the ground until the bottoms of them split into small white flags of surrender and you will also believe that I dreamed of having enough money to buy my way into the kind of infamy that came with surviving any kind of proximity to poverty. You will believe, then, that I remember all of this by the way the ball felt in my hands as I stood on the court alone the next day, pulling the wet ball from one hand to the next and feeling the water spin off of it. You will believe that I only imagined the defender I was breezing past, and

...more

Abdurraqib indicts the country doing the police work of this constraint—not through a direct admonition, but through the kind of quietly damning observation we Midwesterners so excel at.

In They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us, everything is quite literally everything. Race is music is love is America is death is rebirth is brotherhood is growing up is a mother is music is music is music is music. Everything is everything.

Hanif would probably laugh at this because I don’t think he counts himself as any sort of optimist, but this book makes me almost believe in things I thought I’d given up on. I might even dance again, daring to move my legs across this wasted land.

When Marvin Gaye sang the National Anthem at the 1983 NBA All-Star Game, he knew he was going to die soon.

There are days when the places we’re from turn into every other place in America. I still go to watch fireworks, or I still go to watch the brief burst of brightness glow on the faces of black children, some of them have made it downtown, miles away from the forgotten corners of the city they’ve been pushed to. Some of them smiling and pointing upwards, still too young to know of America’s hunt for their flesh. How it wears the blood of their ancestors on its teeth.

there is sometimes only one single clear and clean surface on which to dance, and sometimes it only fits you and no one else.

I mean the gospel is, in many ways, whatever gets people into the door to receive whatever blessings you have to offer.

Everyone I knew needed blessings in 2016. The world, it seemed, was reaching yet another breaking point in a long line of breaking points.

There were funerals I missed, and funerals I didn’t. People I loved walked out of doors they didn’t walk back through.

It isn’t hard to sell people on optimism, but it’s hard to keep them sold on it, especially in a cynical year.

Joy, or the concept of joy, is often toothless and vague because it needs to be. It is both hollow and touchable, in part because it is something that can’t be explained as well as it can be visualized and experienced.

A lot of white people love Chance The Rapper, which makes me reluctant to paint him as some smiling and dancing young black artist, appealing to the white masses. There is a lot to be made out of Chance’s relationship to white rap fans, and how he, as an artist, manages to maintain that relationship while not straying from his reliance on the roots of black church music, and the spirit of black preaching.

I think, though, that a natural reaction to black people being murdered on camera is the notion that living black joy becomes a commodity—something that everyone feels like they should be able to consume as a type of relief point.

Unlike any other city in its region, Chicago sits at the center of the national conversation, taking up space in exciting, uncomfortable ways. Its name is deployed by politicians who imagine any place black people live as a war zone.

The soundtrack to grief isn’t always as dark as the grief itself. Sometimes what we need is something to make the grief seem small, even when you know it’s a lie.

It is one thing to be good at what you do, and it is another thing to be good and bold enough to have fun while doing it. It keeps us on that thin edge of annoyance and adulation.

The truth is that I, like so many of you, spent 2016 trying to hold on to what joy I could. I, like so many of you, am now looking to get my joy back, after it ran away to a more deserving land than this one.

And maybe this is what it’s like to live in these times: the happiness is fleeting, and so we search for more while the world burns around us.

There is optimism in that, too, in knowing that more happ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

When you watch hope closely enough, manifested in enough people, you can start to feel it too.

What Chicago poet Gwendolyn Brooks was most aiming toward, I think, was freedom. Freedom for herself, of course, but also freedom for her people—or at least knowing that one can’t come without the other.

To turn your eye back on the community you love and articulate it for an entire world that may not understand it as you do. That feels like freedom because you are the one who controls the language of your time and your people, especially if there are outside forces looking to control and commodify both.

Chance’s biggest strength is his remarkable ability to pull emotion out of people and extend those feelings into a wide space. But he is also a skilled writer, one who you can tell was molded through Chicago’s poetry and open-mic scene.

He is the type of writer I love most: one who thinks out loud and allows me to imagine the process of the writing.

He stacks rhymes in exciting and unique ways; his delivery is the type that seems entirely unrestrained bu...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

His breath control allows for a cadence that seamlessly dances between rapping and singing. There is an urgency in his writing, the idea that he truly believes that this is more than just rap.

when I call my friends from Chicago who are artists, and we only get five minutes into conversation before they want to know what I’m working on, or how they can help. It is fitting that Chance comes from a city that never lets you walk alone.

He’s also young, and an activist learning to be an activist in these times, as we all are. It’s thrilling, sure, to see so many artists and athletes figuring out how to navigate their role in the political landscape.

There is global activism, but there is also the work of turning and facing your people, which has to become harder with the more distance put between you and those people.

The truth is, if we don’t write our own stories, there is someone else waiting to do it for us. And those people, waiting with their pens, often don’t look like we do and don’t have our best interests in mind.

this is about the choir and about those who might be bold enough to join it before another wretched year arrives to erase another handful of us. This is, more than anything, about those still interested in singing. Say a prayer before you take off. Say a prayer when you land.

To watch Bruce Springsteen step onto a stage in New Jersey is to watch Moses walk to the edge of the Red Sea, so confident in his ability to perform a miracle, to carry his people to the Promised Land. I believe in the magic of seeing a musician perform in the place they once called home.

I imagine, though, that this could be overwhelming for someone who has never seen Springsteen live. The chanting and relentless fist-pumping beforehand while the stage is being set up, the American flags wrapped around foreheads or hanging off of backs. From another angle, this may feel like a strange political rally. On its face, it matches the tone, passion, and volume of political theater at its base form.

Whether or not the preacher himself intends this, in the church of Bruce Springsteen, it is understood that there is a singular America, one where there is a dream to be had for all who enter, and everyone emerges, hours later, closer to that dream.

Unlike New Jersey on the night of Bruce Springsteen’s homecoming, the air in Ferguson still feels heavy, thick with grief. Yet it is still a town of people who take their joy where they can get it, living because they must.

There is a part of me that has always understood The River to be about this. Staring down the life you have left and claiming it as your own, living it to the best of your ability before the clock runs out.

the promise that has always been sold in Bruce Springsteen’s music. The ability to make the most out of your life, because it’s the only life you have.

Here is where I tell you that this was a sold-out show, and as I looked around the swelling arena when I arrived, the only other black people I saw were performing labor in some capacity.

In Bruce Springsteen’s music, not just in The River, I think about the romanticization of work and how that is reflected in America. Rather, for whom work is romantic, and for whom work is a necessary and sometimes painful burden of survival. One that comes with the shame of time spent away from loved ones, and a country that insists you aren’t working hard enough.

Springsteen’s songs are the same anthemic introspective paintings of a singular America: men do labor that is often hard, loading crates or working on a dock, and there is often a promised reward at the end of it all. A loving woman always waiting to run away with you, a dance with your name on it, a son who will grow up and take pride in the beautiful, sanctifying joy of work.

I know that I understand being black in America, and I have understood being poor in America. What I know comes with both of those things, often together, is work that is always present, the promise of more to come.