More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

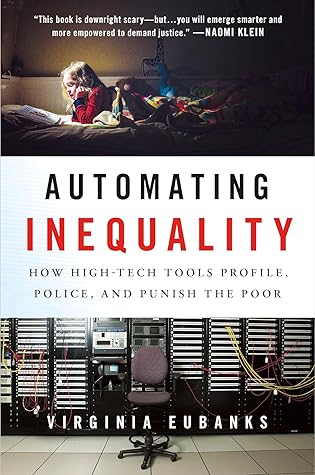

Technologies of poverty management are not neutral. They are shaped by our nation’s fear of economic insecurity and hatred of the poor; they in turn shape the politics and experience of poverty.

Caseworkers assumed that the poor were not reliable witnesses. They confirmed their stories with police, neighbors, local shopkeepers, clergy, schoolteachers, nurses, and other aid societies.

they believed that there was a hereditary division between deserving and undeserving poor whites.

More quietly, program administrators and data scientists push high-tech tools that promise to help more people, more humanely, while promoting efficiency, identifying fraud, and containing costs. The digital poorhouse is framed as a way to rationalize and streamline benefits, but the real goal is what it has always been: to profile, police, and punish the poor.

The obsession with “personal responsibility” makes our social safety net conditional on being morally blameless. As political theorist Yascha Mounk argues in his 2017 book, The Age of Responsibility, our vast and expensive public service bureaucracy primarily functions to investigate whether individuals’ suffering might be their own fault.

We have all always lived in the world we built for the poor. We create a society that has no use for the disabled or the elderly, and then are cast aside when we are hurt or grow old. We measure human worth based only on the ability to earn a wage, and suffer in a world that undervalues care and community. We base our economy on exploiting the labor of racial and ethnic minorities, and watch lasting inequities snuff out human potential. We see the world as inevitably riven by bloody competition and are left unable to recognize the many ways we cooperate and lift each other up.