More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Today, we have ceded much of that decision-making power to sophisticated machines. Automated eligibility systems, ranking algorithms, and predictive risk models control which neighborhoods get policed, which families attain needed resources, who is short-listed for employment, and who is investigated for fraud.

There is no requirement that you be notified when you are red-flagged.

Our world is crisscrossed with informational sentinels like the system that targeted my family for investigation.

In his famous novel 1984, George Orwell got one thing wrong. Big Brother is not watching you, he’s watching us. Most people are targeted for digital scrutiny as members of social groups, not as individuals.

Marginalized groups face higher levels of data collection when they access public benefits, walk through highly policed neighborhoods, enter the health-care system, or cross national borders. That data acts to reinforce their marginality when it is used to target them for suspicion and extra scrutiny. Those groups seen as undeserving are singled out for punitive public policy and more intense surveillance, and the cycle begins again. It is a kind of collective red-flagging, a feedback loop of injustice. For example, in 2014

The transactions that LePage found suspicious represented only 0.03 percent of the 1.1 million cash withdrawals completed during the time period, and the data only showed where cash was withdrawn, not how it was spent. But the governor used the public data disclosure to suggest that TANF families were defrauding taxpayers by buying liquor, lottery tickets, and cigarettes with their benefits. Lawmakers and the professional middle-class public eagerly embraced the misleading tale he spun from a tenuous thread of data.

The legislation was not intended to work; it was intended to heap stigma on social programs and reinforce the cultural narrative that those who access public assistance are criminal, lazy, spendthrift addicts.

Technologies of poverty management are not neutral.

The cheerleaders of the new data regime rarely acknowledge the impacts of digital decision-making on poor and working-class people.

“You should pay attention to what happens to us. You’re next.”

The three stories capture different aspects of the human service system: public assistance programs such as TANF, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), and Medicaid in Indiana; homeless services in Los Angeles; and child welfare in Allegheny County. They also provide geographical diversity: I started in rural Tipton County in America’s heartland, spent a year exploring the Skid Row and South Central neighborhoods of Los Angeles, and ended by talking to families living in the impoverished suburbs that ring Pittsburgh.

What Eubanks is doing here is showing how her case studies are similar and different - what axes she differentiates on and how they are contextually different.

What I found was stunning. Across the country, poor and working-class people are targeted by new tools of digital poverty management and face life-threatening consequences as a result.

Automated decision-making shatters the social safety net, criminalizes the poor, intensifies discrimination, and compromises our deepest national values. It reframes shared social decisions about who we are and who we want to be as systems engineering problems.

And while the most sweeping digital decision-making tools are tested in what could be called “low rights environments” where there are few expectations of political accountability and transparency, systems first designed for the poor will eventually be used on everyone.

Today, we have forged what I call a digital poorhouse from databases, algorithms, and risk models. It promises to eclipse the reach and repercussions of everything that came before.

But the poorhouse was once a very real and much feared institution. At their height, poorhouses appeared on postcards and in popular songs.

Despite optimistic predictions that poorhouses would furnish relief “with economy and humanity,” the poorhouse was an institution that rightly inspired terror among poor and working-class people.

While poorhouses have been physically demolished, their legacy remains alive and well in the automated decision-making systems that encage and entrap today’s poor. For all their high-tech polish, our modern systems of poverty management—automated decision-making, data mining, and predictive analytics—retain a remarkable kinship with the poorhouses of the past.

But in America, middle-class commentators stoked fears of class warfare and a “great Communist wave.”7 As they had following the 1819 Panic, white economic elites responded to the growing militancy of poor and working-class people by attacking welfare. They asked: How can legitimate need be tested in a communal lodging house? How can one enforce work and provide free soup at the same time? In response, a new kind of social reform—the scientific charity movement—began an all-out attack on public poor relief.

Scientific charity treated the poor as criminal defendants by default.

The movement’s focus on heredity was influenced by the incredibly popular eugenics movement.

The scientific charity movement relied on a slew of new inventions: the caseworker, the relief investigation, the eugenics record, the data clearinghouse. It drew on what lawyers, academics, and doctors believed to be the most empirically sophisticated science of its time. Scientific charity staked a claim to evidence-based practice in order to distinguish itself from what its proponents saw as the soft-headed emotional, or corruption-laden political, approaches to poor relief of the past. But the movement’s high-tech tools and scientific rationales were actually systems for disempowering poor

...more

and because they abandoned the in-depth investigations pioneered by scientific charity caseworkers.

They were more intrusive because income limits and means-testing rationalized all manner of surveillance and policing of applicants and beneficiaries.

These legal victories established a truly revolutionary precedent: the poor should enjoy the same rights as the middle class.

As backlash against welfare rights grew, news coverage of poverty became increasingly critical.

They commissioned expansive new technologies that promised to save money by distributing aid more efficiently. In fact, these technological systems acted like walls, standing between poor people and their legal rights. In this moment, the digital poorhouse was born.

Berlinger proposed a central computerized registry for every welfare, Medicaid, and food stamp recipient in the state. Planners folded Rockefeller’s fixation with ending the welfare “gravy train” into the system’s design. The state hired Ross Perot’s Electronic Data Systems to create a digital tool to “reduce well documented ineligibility, mismanagement and fraud in welfare administration,” automate grant calculations and eligibility determinations, and “improve state supervision” of local decision-making.20 Design, development, and implementation of the resulting Welfare Management System

...more

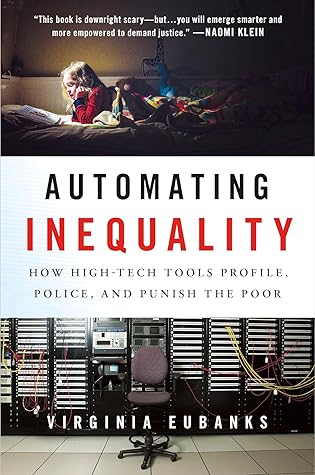

The digital poorhouse is framed as a way to rationalize and streamline benefits, but the real goal is what it has always been: to profile, police, and punish the poor.

In 2012, I delivered a lecture at Indiana University Bloomington about how new data-based technologies were impacting public services. When I was finished, a well-dressed man raised his hand and asked the question that would launch this book. “You know,” he asked, “what’s going on here in Indiana, right?” I looked at him blankly and shook my head. He gave me a quick synopsis: a $1.3 billion contract to privatize and automate the state’s welfare eligibility processes, thousands losing benefits, a high-profile breach-of-contract case for the Indiana Supreme Court. He handed me his card. In gold

...more

Performance metrics designed to speed eligibility determinations created perverse incentives for call center workers to close cases prematurely. Timeliness could be improved by denying applications and then advising applicants to reapply, which required that they wait an additional 30 or 60 days for a new determination. Some administrative snafus were simple mistakes, integration problems, and technical glitches. But many errors were the result of inflexible rules that interpreted any deviation from the newly rigid application process, no matter how inconsequential

or inadvertent, as an active refusal to cooperate.

Failure to cooperate notices offered little guidance. They simply stated that something was not right with an application, not what specifically was wrong.

After the automation, the phrase became a chain saw that clearcut the welfare rolls, no matter the collateral damage.

“I found no documentation of recent payroll information in the computer.

By successfully reframing public benefits as property rather than charity, the welfare rights movement established that public assistance recipients must be provided due process under the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution.

plan anyway.9 The goals of the project were consistent throughout the automation experiment:

maximize efficiency and eliminate fraud by shifting to a task-based system and severing caseworker-to-client bonds. They were clearly reflected in contract metrics: response time

in the call centers was a key performance indicator; determination accuracy was not. Efficiency and savings were built into the contract;...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

“Suitable home” and “employable mother” rules were selectively interpreted to block African American women from claiming their benefits until the rise of the welfare rights movement in the 1970s.

worst effects. Removing human discretion from public assistance eligibility may seem like a compelling solution to the continuing discrimination African Americans face in the welfare system. After all, a computer applies the rules to each case consistently and without prejudice. But historically, the removal of human discretion and the creation of inflexible rules in public services only compound racially disparate harms.

But automated decision-making in our current welfare system acts a lot like older, atavistic forms of punishment and containment. It filters and diverts. It is a gatekeeper, not a facilitator.

In the end, the Indiana automation experiment was a form of digital diversion for poor and working Americans. It denied them benefits, due process, dignity, and life itself. “We were not investing in our fellow human beings the way we should be,” said John Cardwell of The Generations Project. “We were basically saying to a large percentage of people in Indiana, ‘You’re not worth a shit.’ What a horrible waste of humanity.”

Thus, Los Angeles built only a fraction of the number of public housing units of other cities its size, and most of it was built in communities of color.