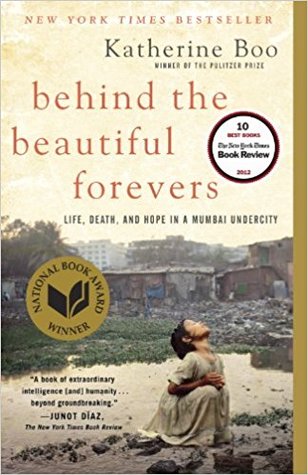

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

June 17 - June 24, 2020

It seemed to him that in Annawadi, fortunes derived not just from what people did, or how well they did it, but from the accidents and catastrophes they dodged. A decent life was the train that hadn’t hit you, the slumlord you hadn’t offended, the malaria you hadn’t caught. And while he regretted not being smarter, he believed he had a quality nearly as valuable for the circumstances in which he lived. He was chaukanna, alert.

Asha had no claims. Her husband was an alcoholic, an itinerant construction worker, a man thoroughgoing only in his lack of ambition. As she’d raised their three children, who were now teenagers, few neighbors thought of her as anyone’s wife. She was simply Asha, a woman on her own. Had the situation been otherwise, she might not have come to know her own brain.

It wasn't what she had - it was what she didn't have or avoided that allowed her to "discover her own brain."

Wealthy citizens accused the slumdwellers of making the city filthy and unlivable, even as an oversupply of human capital kept the wages of their maids and chauffeurs low. Slumdwellers complained about the obstacles the rich and powerful erected to prevent them from sharing in new profit.

Guilt of the sort that had overcome Robert was an impediment to effective work in the city’s back channels, and Asha considered it a luxury emotion. “Corruption, it’s all corruption,” she told her children, fluttering her hands like two birds taking flight.

“The big people think that because we are poor we don’t understand much,” she said to her children. Asha understood plenty. She was a chit in a national game of make-believe, in which many of India’s old problems—poverty, disease, illiteracy, child labor—were being aggressively addressed. Meanwhile the other old problems, corruption and exploitation of the weak by the less weak, continued with minimal interference. In the West, and among some in the Indian elite, this word, corruption, had purely negative connotations; it was seen as blocking India’s modern, global ambitions. But for the poor

...more

The self-help group headed by Asha is yet another example of this - omnipresent dubiousness of the anti-poverty programs, which in its turn allows survival of many weak people over the weaker ones.

The last time Ward 76 had an all-female ballot, Corporator Subhash Sawant had put up his housemaid. The maid had won, and he had kept running the ward. Asha thought that he might just pick her to run in the next all-female election, since his new maid was a deaf-mute—ideal for keeping his secrets, less so for campaigning.

This is one of the worst variations of such ruling I have ever heard of. Some political systems definitely have a similar pattern of real ruler being behind the scenes.

These poor-against-poor riots were not spontaneous, grassroots protests against the city’s shortage of work. Riots seldom were, in modern Mumbai. Rather, the anti-migrant campaign had been orchestrated in the overcity by an aspiring politician—a nephew of the founder of Shiv Sena. The upstart nephew wanted to show voters that a new political party he had started disliked bhaiyas like Abdul even more than Shiv Sena did.

Once again, poor-against-poor concept wasn't born among the poor, it was enforced upon the struggling communities.

Having a sense of how the world operated, beyond its pretenses, seemed to him an armoring thing. And when Sister Paulette decided that boys over eleven years old were too much to handle and Sunil was turned out onto the street, he tried to concentrate on what he had gained in her care.

What a privileged person calls reflection and learning from struggles, for someone like Sunil is a necessity.

And on the streets, new municipal garbage trucks were rolling around, as a civic campaign fronted by Bollywood heroines attempted to combat Mumbai’s reputation as a dirty city. Stylish orange signs above dumpsters were commanding, CLEAN UP! Some freelance scavengers worried that, soon, they would have no work at all.

For slumdwellers working trash, the city becoming less dirty meant no work. Sunil was averaging 15 rupees a day which is about 33 US dollar cents..

Though it, too, had an abundance of young, cheap, trainable labor, there were opportunity costs attached to the fact that the Indian financial capital was alternatively known as Slumbai. Despite economic growth, more than half of Greater Mumbai’s citizenry lived in makeshift housing.

With Shanghai and Singapore thriving with the British and American capital, Indian financial image was spoiled by the notion of Slumbai (Mumbai as the financial capital was the focus). Hence, Indian sensitivity about its slums.

Abdul recognized this tendency to get punchy about discoveries to which other people were indifferent. He no longer tried to explain his private enthusiasms, and figured Sunil would learn his own aloneness, in time.

Learning one's aloneness - wow, that is just profound. For people like Sunil who lives in a slum, the surroundings should define who he is and his interests (the interest of survival). If there's anything beyond that interest - it means aloneness.

Young girls in the slums died all the time under dubious circumstances, since most slum families couldn’t afford the sonograms that allowed wealthier families to dispose of their female liabilities before birth.

The Indian criminal justice system was a market like garbage, Abdul now understood. Innocence and guilt could be bought and sold like a kilo of polyurethane bags.

Although public funds for education had increased with India’s new wealth, the funds mainly served to circulate money through the political elite. Politicians and city officials helped relatives and friends start nonprofits to secure the government money. It was of little concern to them whether the schools were actually running.

Every country has its myths, and one that successful Indians liked to indulge was a romance of instability and adaptation—the idea that their country’s rapid rise derived in part from the chaotic unpredictability of daily life. In America and Europe, it was said, people know what is going to happen when they turn on the water tap or flick the light switch. In India, a land of few safe assumptions, chronic uncertainty was said to have helped produce a nation of quick-witted, creative problem-solvers.

In the age of global market capitalism, hopes and grievances were narrowly conceived, which blunted a sense of common predicament. Poor people didn’t unite; they competed ferociously amongst themselves for gains as slender as they were provisional. And this undercity strife created only the faintest ripple in the fabric of the society at large. The gates of the rich, occasionally rattled, remained un-breached. The politicians held forth on the middle class. The poor took down one another, and the world’s great, unequal cities soldiered on in relative peace.

But as capital rushes around the planet and the idea of permanent work becomes anachronistic, the unpredictability of daily life has a way of grinding down individual promise. Ideally, the government eases some of the instability. Too often, weak government intensifies it and proves better at nourishing corruption than human capability.

In places where government priorities and market imperatives create a world so capricious that to help a neighbor is to risk your ability to feed your family, and sometimes even your own liberty, the idea of the mutually supportive poor community is demolished. The poor blame one another for the choices of governments and markets, and we who are not poor are ready to blame the poor just as harshly.