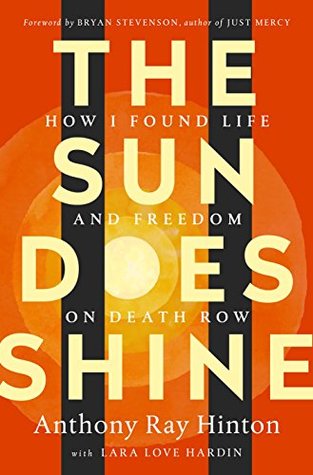

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

July 31 - August 19, 2022

Most of us can’t possibly imagine what it feels like to be arrested, accused of something horrible, imprisoned, wrongly convicted because we don’t have the money needed to defend ourselves, and then condemned to execution. For most people, it’s simply inconceivable. Yet, it’s important that we understand that it happens in America and that more of us need to do something to prevent it from happening again.

He was a poor man in a criminal justice system that treats you better if you are rich and guilty than if you are poor and innocent.

But pain and tragedy and injustice happen—they happen to us all. I’d like to believe it’s what you choose to do after such an experience that matters the most—that truly changes your life forever. I’d really like to believe that.

But justice is a funny thing, and in Alabama, justice isn’t blind. She knows the color of your skin, your education level, and how much money you have in the bank. I may not have had any money, but I had enough education to understand exactly how justice was working in this trial and exactly how it was going to turn out. The good old boys had traded in their white robes for black robes, but it was still a lynching.

He was officially assigned my case, and I heard him mumble, “I didn’t go to law school to do pro bono work.” I cleared my throat, and he looked me in the eye for the first time. Even though I was handcuffed and chained, I held out my hand to shake his. “Would it make a difference if I told you I was innocent?” “Listen, all y’all always doing something and saying you’re innocent.” I dropped my hand. So that’s how it was going to be. I was pretty sure that when he said “all y’all,” he wasn’t talking about ex-cons or former coal miners or Geminis or even those accused of capital murder.

I was on death row not by my own choice, but I had made the choice to spend the last three years thinking about killing McGregor and thinking about killing myself. Despair was a choice. Hatred was a choice. Anger was a choice. I still had choices, and that knowledge rocked me. I may not have had as many as Lester had, but I still had some choices. I could choose to give up or to hang on. Hope was a choice. Faith was a choice. And more than anything else, love was a choice. Compassion was a choice.

I was born with the same gift from God we are all born with—the impulse to reach out and lessen the suffering of another human being. It was a gift, and we each had a choice whether to use this gift or not.

I knew he was thinking of Michael Donald, the boy that he had killed. I knew he wondered what that boy might have grown up to become. Henry was the first white man to be put to death for killing a black in almost eighty-five years. His death meant something to people outside of the row. It was making a point about racism and justice and fairness like all the books we had been reading in book club, but to us, it was a family member being killed. There’s no racism on death row.

We banged and we yelled and we hollered as loud as we could. For fifteen minutes, I screamed until my throat was raw and hoarse. I screamed so Henry would know that he meant something. I screamed so that whoever was there to watch the State of Alabama kill in their name knew that we were real men and that you couldn’t hide us under a black hood and pretend we didn’t feel pain. I screamed because I knew that innocent men had been strapped into that horrid yellow chair, their heads shaved like a bad dog, their dignity stripped away little by little, their worth as humans tied up with electric

...more

He listened to everything I said. He didn’t seem in a rush to finish. He didn’t interrupt me. He just listened. It was a powerful thing to be listened to like that.

What kind of a world was it where an innocent man can lose sixteen years of his life and it’s a waste of time to let him prove he’s innocent?

Until we have a way of ensuring that innocent men are never executed—until we account for the racism in our courts, in our prisons, and in our sentencing—the death penalty should be abolished.

I was tired, and I didn’t pray any longer for the truth to be known. The truth was known. Alabama knew I was innocent, but they would never admit it. They wouldn’t in 1986. They wouldn’t in 2002. They wouldn’t in 2005. And they weren’t going to in 2013.

You can’t threaten to kill someone every day year after year and not harm them, not traumatize them, not break them in ways that are really profound. —BRYAN STEVENSON