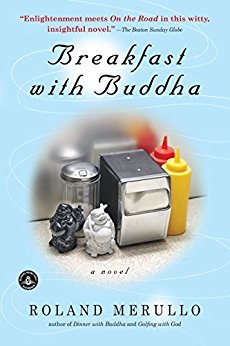

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

To my shock, to my dismay, it turned out that the “something a little else” Rinpoche had referred to was a yoga class.

I looked at Rinpoche with what must have been a pleading expression, because he squeezed my arm harder and told me I shouldn’t worry, that I was a good man, that I was his good and special friend.

Molly introduced the Rinpoche as a great holy man and yogi and then introduced me as his associate, “first student,” and traveling companion. My face was the color of a persimmon.

It was a case of mistaken identity!

Ognipassineh. Silsa rannawathana. Boothanagan masi.

Downward facing dog. Upward facing dog. Dog facing death.

At last, after what seemed like the better part of a school year had passed, Molly called for something named, appropriately enough it seemed to me, corpse pose, or death pose.

But after several minutes of stewing, I noticed that a wonderful whole-body calm was coming over me. I had not relaxed like that in decades, if ever. Every fiber of my body, every cell from the soles of my feet to my scalp, had been worked, and now they were at rest, and my mind slowly joined them. It was not like sleep, I was not drowsy at all, but a kind of sunny calm descended over my thoughts.

For the space of eight or ten seconds, something, some process or interior habit, had been suspended, and in those seconds, wordlessly, I thought I had seen or understood something, and I kept reaching back to retrieve that understanding, and my mind kept tripping over its old habits and bouncing away.

A fair portion of my anger had returned, but alongside it ran the memory of those few seconds on the yoga mat in the death pose. I felt as if I had been shown a kind of essential secret, something so subtle and quiet and small (and yet so important) that I could have gone my entire adult life and never even imagined such a thing existed. As I reflected on it, I realized that I’d experienced somewhat similar moments—watching the sun go down from a beach

just lying in bed on a Saturday when the children were small and safely asleep on my chest. But those flashes of peace seemed somehow accidental, and they bore a resemblance to what I’d felt in that overheated yoga studio in the same way that a kiss on the cheek by a nice aunt bears a resemblance to an orgasm with the person you love. A lush new field had become part of my interior world, and it was difficult to sustain anger under the open sky.

“Just when I was starting to trust you, to really listen to you, you tricked me into doing that yoga class.” He nodded again, waiting. “At least you could have let me be in the back row so everyone couldn’t see me make a fool of myself.” Another nod. More attentive stillness. At last he spoke, “Is Otto finished being angry now?” “Pretty much, yes.” Nod number four. “Are you ready to become the new Otto, or do you want to stay the old Otto?”

“Today, you had a little bit of while when you were the new Otto.” “Where? When?” “Corpse pose. A few seconds.” “How would you know that?” “I see it.” “How do you see it? Where? My aura?” He chuckled and shook his head. “It was pleasure-making to you, yes?” “Yes.” “New pleasure, yes? Different.” “Yes, I admit that.”

“Then I will show you more, but if you want to be angry with me I can’t show you. Anger is like hands over your eyes when another person is trying to show you.”

That is what meditation is: You see the thought and you let it float away, see the thought and let it float away. Maybe you say to yourself, That is only a thought.

Breathe in and breathe out. You will think about your family, your work, about me sitting beside you, about many, many things that are interesting to think about. This is like the bird knocking. You cannot make a home in those things. They are not bad, they are just not the right home for Otto. Do not get upset because your mind thinks about them. Do not push the thoughts away like they are bad things. Let them go away from you but do not push them, yes? But always come back to the feeling on your mouth, and breathe in and breathe out.

ablutions

“And this always thinking about the next pleasure, this is not so bad. Except it keeps your mind from how it could be calm in this moment. This can happen on a very subtle level, or not so. If you don’t eat for a little while when you can, or don’t sex for a little while when you can, then you see better the way the mind makes the world for you.” “And that does what, exactly? Abstaining, I mean.” “Makes the glass more clear. When your mind is more clear, you see the true way the world is made. When you see the true way the world is made, you feel at peace inside. You see how you make your own

...more

“That is the blue space, what you felt.”

The people who made those paintings of Jesus and Mary could understand this, what I am saying. In that space there is no anger, no killing, no war, no wanting food or sex all the time. And no fear of dying.”

Don’t think so much now, just whenever you want to think so much take a nice breath, listen to the tires’ noise on the road, look at the trees, look at the lake, look at the other cars, feel inside when you are breathing, feel the pain in your muscles. That is what yoga does for anyone, makes you to pay attention, not to think. Do not force information into your mind. You are smart now, you will always be smart, but if you think too much it pushes you from God.”

I supposed it was true that certain distractions were better than others. Looking at a great painting or reading a great book might turn your mind in the direction of the pleasurable emptiness; watching babysitters and jilted wives fighting on a TV show probably would not.

It seemed to me that Rinpoche was making the opposite point: that I was in control of my spiritual situation, not God; that we had been given the tools for an expanded consciousness and it was up to us to use them, not simply wait around for death and salvation.

Rinpoche was telling me not to think, but it was my thinking, my thirst for learning, that had led me to break the mold of my parents’ expectations and go off to college

in Grand Forks, then to graduate school in Chicago, then pack a suit and some city clothes and, with Jeannie, head east for New York City, capital of the thinking world. Now, Rinpoche seemed to be encouraging me to go home, back to a calmer, slower world, and it was not an easy trip.

“We teach,” Eveline told him. “There is a large university here, in Duluth, actually. I teach English and Matthew teaches philosophy.”

“Honey, these aren’t words he understands, you can see that.” “I thought he might intuit,” Matthew said. And at that I could not stop myself from saying, “He speaks eleven languages.” Matthew drew his head back in surprise, actual or feigned, I could not tell. “Really. Say something, then, in Italian, or Russian, or Greek. Or are they languages none of us might know, your eleven?” Rinpoche looked at him for a long moment, until the silence grew awkward around us, and then he said, “Kindness is one language I know.” And he spoke the phrase kindly, too, as if it were simply a statement of fact.

Matthew did not take it that way. “Am I being unkind? Mea culpa, as they say in Latin. Forgive me, Rinpoche. I don’t mean it personally, really. It’s just that I find the whole Buddhist, or almost Buddhist philosophy patently absurd. If nothingness is the point, why bother? If we must strain, struggle, and contemplate our thought processes in this life with the goal of the obliteration of our own ego, our self, well, it hardly seems worth the trouble to me, though I suspect you’d disagree.”

“It’s a question of a sound philosophy or some kind of antisolipsistic shoddiness.” “He wouldn’t know the word, dear.” “Nonsense, then, some kind of nonsense,” Matthew said. “Could be nonsense.” Rinpoche put a hand on Matthew’s arm as if to calm him, or to turn him back to facing us. “Could be. How do we test?” “In our tradition,” Matthew said, “the test for thousands of years has been something we call logic.”

“And, frankly, I’ve never found Buddhism to be able to pass. No offense, please.” “You could not offend me.”

“While you’re practicing your eleven languages, no doubt.” “Honey!” Eveline interjected. “Why are you being so mean to the man? He’s done nothing to us, and it was you who invited him to join us, after all.”

I could see, in his angular face, something like the expression I’d seen on the features of the nun at Notre Dame, something like the emotion I’d felt in myself during the first few conversations with my traveling pal. Rinpoche’s way of being—his personality or his voice or his face—brought out a kind of terror that lurked inside people like us, thought-full people. The terror had been sleeping peacefully until he showed up with his bald head and maroon robe, his calm demeanor.

Matthew didn’t seem to hear. He focused his wide-set blue eyes on Rinpoche’s face. “What say you, sir? A duel. Western rationalism versus the filly-fally of the East, played out upon the transcendental field of the miniature golf course. The winner gets to ask the loser a koan—that’s fair, isn’t it? And the loser cannot eat his

evening meal until the koan is answered to the winner’s satisfaction.”

Rinpoche’s wide face had gone unreadable. I was trying to get his attention, to give him a signal: NO! In case you lose. . . . We have to eat. . . . So don’t! ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

He made a quick little swing and the ball climbed smoothly over the first hill, then over the second, losing speed and just barely reaching the crest of the third, and then it dropped down in a straight line right into the cup.

Either Rinpoche had played golf before, had a natural aptitude for the game, or, my personal theory, was working some kind of yogic magic, because he made two more holes in one.

Rinpoche was studying the angular face as if it were a painting. “You want a question?” he asked. “Yes, a koan.” “But in my lineage we do not use koans.”

“Make something up then. Surely you have a test for me.”

“My question is,” he freed his right hand from the cloth of his robe, held it up, and brought the thumb and third finger together in a circle. He held the circle for a moment, then opened his hand. “If I think make a circle and my hand does not, what is happening?” “I don’t follow.”

“Look, my hand is open now, yes?” “Yes.” “But I am thinking to my hand: Make a circle. But it is not making a circle. What is happening?” Matthew frowned. “That’s obvious. Another part of you is overriding the order. You are thinking, Make a circle, but another part of you, call it the will, is not going along with the order.” “Excellent,” Rinpoche said.

“You’ve played miniature golf before, haven’t you?” I said, when the hot drinks had been served and sipped. “In Europe,” he said, “at my center, I have a very rich student, and this man sometimes takes me to play golf. Big golf. On his very nice course.”

“They were good people, the professors at the golf.” “She was nice, but I found him very hard to be around. That kind of humor, that . . . I don’t know.”