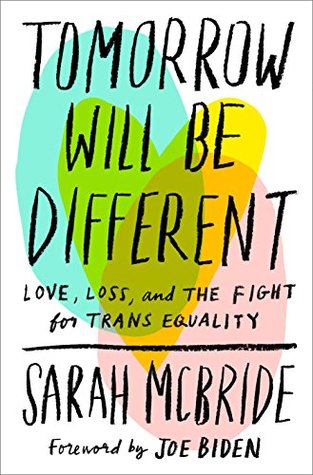

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Together, on that night, it felt like our campus was sending a small but powerful message: that for transgender people, tomorrow can be different.

It doesn’t always get better. Sometimes it is a step back; it’s the loss of a life, an act of hate, or the rescinding of rights

in states like North Carolina and in the military. It’s the perpetuation of a status quo in which a majority of states and the federal government still lack clear protections from discrimination for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer people; where too many remain at risk of being fired from their ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

When I came out, I never anticipated just how far the LGBTQ community and movement would come in so short a time. Inheriting a legacy of advocates, activists, and everyday people who, through the flames of violence and the ashes of hatred, toiled and fought for a different world, we’ve grown into one of the most effective movements for social justice in history. And even as we’ve faced some crushing defeats, transgender people—and all LGBTQ individuals—have made historic advancements.

After a decade of unprecedented progress, the knowledge that change is possible, the hope of a better day, is the fuel that drives us. We strive toward a world where every person can live their life to the fullest. While the progress is uneven and can come in fits and starts, I still know today—years after that night at American University—that, with hard work and compassion, we can make more tomorrows better than today.

When the boys and girls would line up separately in kindergarten, I’d find myself longing to be in the other line. The rigid and binary gender lines are made abundantly clear to all of us at a young age, from the color-coded clothing to “boy’s toys” and “girl’s toys.” For a five-year-old, the distance between the two gendered lines in kindergarten might as well be a mile apart. It was clear: There was no crossing of the divide, under any circumstances.

As the questions went on, it became clear that my parents were struggling with the same empathy gap that I later would realize was one of the main barriers to trans equality among progressive voters: They couldn’t wrap their minds around how it might feel to have a gender identity that differs from one’s assigned sex at birth.

“The best way I can describe it for myself,” I told them, “is a constant feeling of homesickness. An unwavering ache in the pit of my stomach that only goes away when I can be seen and affirmed in the gender I’ve always felt myself to be. And unlike homesickness with location, which eventually diminishes as you get used to the new home, this homesickness only grows with time and separation.”

My dad, a longtime progressive, also said that he didn’t understand how one could feel like something that is a social construct. Wasn’t gender, and all the things associated with it, just a creation of society? Wasn’t that what feminism had taught us? I explained to him that, for me, gender is a lot like language. Language, too, is a social construct, but one that expresses very real things. The word “happiness” was created by humans, but that doesn’t diminish the fact that happiness is a very real feeling. People can have a deeply held sense of their own gender even if the descriptions,

...more

I awoke the next day at seven a.m. to my parents opening my door. As soon as I opened my eyes and saw them, I could tell that neither had slept, and that the crying, which had subsided by evening, had returned. This time, though, both of them were sobbing. My parents walked to either side of my bed and got in with me, still crying. They both held me and pleaded again and again: “Please don’t do this. Please don’t do this. Please don’t do this.” I let them cry and tried to tell them that it would be okay, but I couldn’t provide them with the response they hoped for. I hated to see my parents

...more

Sitting downstairs with my mom, Sean took some of the load off me and answered some of their questions. I think he also knew that my news was so shocking that having a second person to validate what I had said would help my parents digest the reality of the situation. “What are the chances? I mean, what are the chances I have both a gay son and a transgender child?” my mom asked Sean. “Mom, what are the chances a parent finds out that their

child has terminal cancer?” Sean, a radiation oncologist, replied. “Your child isn’t going anywhere. No one is dying.” It was the response she needed. She needed someone to push back and not feel sorry for her. She needed someone to put things into perspective.

Soon enough, I hoped we would all come to the place where she could ask that same question, “What are the chances?,” out of awe and not out of self-pity—a place where my parents could see that they had raised children who were confident and strong enough to live their truths and whose different perspectives enhanced our family’s beauty...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Most people are good, no doubt, but when we are faced with issues we haven’t yet thought about or interacted with, we often look to one another for how we should respond. Our behavior models for others the acceptable reaction; acceptance creates an expectation, while rejection provides an excuse.

Each of us has a deep and profound desire to be seen, to be acknowledged, and to be respected in our totality. There is a unique kind of pain in being unseen. It’s a pain that cuts deep by diminishing and disempowering, and whether done intentionally or unintentionally, it’s an experience that leaves real scars.

Even for the most well-intentioned person, it may be difficult to separate an individual’s gender identity from the sex assigned to them based on the appearance of external anatomy. We’ve been taught and raised to believe that these two concepts are inextricably joined, that one not only leads to the other, but that they are actually one and the same.

It is this trend that links the fight for gender equity with the fight for gay rights with the fight for trans equality: ending the notion that one perception at birth, the sex we are assigned, should dictate how we act, what we do, whom we love, and who we are.

When we finally separate that perception from those expectations, we allow ourselves to witness the wholeness of other human beings. This effort—coupled with the overlapping fights for racial justice, disability rights, and equality for religious minorities—shares a similar thread. We are fighting to be seen in our personhood, in our worth, in our love, and as ourselves.

In other battles for trans rights, anti-equality activists and politicians had stoked unfounded fears that protecting transgender people from discrimination throughout daily life, including in restrooms, would allow sexual predators to dress up as women to harm or assault women and, particularly, young girls.

The argument was completely disingenuous. A person intent on committing a crime in a restroom is offered no cover from laws that merely protect transgender people from discrimination or harassment. More than a dozen states and more than a hundred cities had passed similar bills without any problems of that kind. These arguments were just recycled talking points from previous gay-rights fights.

“Protect our children,” read the antigay signs in the 1970s and ’80s. “Preserve parents’ rights to protect their children from teachers who are immoral and who promote a perverted lifestyle.” Just as these arguments preyed on people’s stereotypes and ignorance about gay identities, so too do these new antitrans arguments. ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

One of the more common refrains we heard from legislators, both in support and in opposition, was that they did not have any transgender people in their districts. It was an absurd conclusion to draw; after all, there were forty-one House districts and twenty-one Senate districts. Delaware is small, but even conservative counts estimated that at least two thousand transgender people lived in our state of roughly nine hundred thousand people. Later studies would estimate the transgender population in Delaware to be closer to 4,500.

A government cannot be “of the people, by the people, and for the people” if wide swaths of the people have no seat at the table, if large parts of the country feel like there is literally no one in their government who can understand what they are going through.

The discomfort of others shouldn’t be grounds for differential treatment. And when you do that, when you single us out, it puts a bull’s-eye on our backs for harassment and bullying and reinforces the prejudice that we are not really the gender we are.

Until every single LGBTQ person is protected by the law and treated with fairness, our fight isn’t over. A person’s safety or dignity should not depend on their state or zip code. Equal means equal. But a majority of states still lacked the same basic yet critical protections from discrimination that we had just fought so hard for in Delaware.

Even with a supportive, progressive family, hate had kept Andy inside himself for what turned out to be the majority of his life. None of us know how long we have, but we do have a choice in whether we love or hate. And every day that we rob people of the ability to live their lives to the fullest, we are undermining the most precious gift we are given as humans.

It’s not often you know that you’re witnessing history when it’s happening, but that realization was unmistakable in 2015 and 2016. Our community’s progress would have seemed unimaginable just a decade before. But because of the tireless work of advocates and activists and the quiet courage of everyday LGBTQ people, “the arc of the moral universe” was bending toward justice. As broken as our politics can seem, our community proved that we can still do big things in this country, that when we advocate from a place of passion and authenticity, change will come.

Just a month after passage of the law, I flew down to North Carolina with a film crew from CAP to interview an eighteen-year-old transgender boy about HB2. Finn Williams lived just outside Durham, North Carolina, and had come out to a supportive family a few years before. After coming out, Finn had gone to four different schools trying to find one that would both allow him to use the boys’ restroom and combat the bullying he experienced. In denying Finn access to the boys’ restroom, he was told that he would make the other students

uncomfortable. “Just being me shouldn’t make other people uncomfortable,” Finn told us. He eventually dropped out of high school entirely instead of facing the constant bullying from peers and humiliation by his school. And now the North Carolina legislature had mandated effectively the same treatment Finn had experienced for the thousands of transgender students statewide. After finishing up with Finn, we traveled to Charlotte and met with a member of the city council, a trailblazing out lesbian woman named LaWana Mayfield who had helped lead the charge for the city’s now-banned LGBTQ

...more