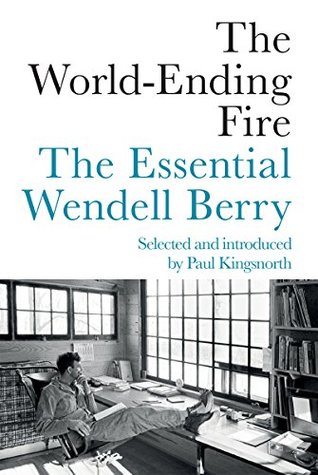

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

October 6, 2021 - June 11, 2022

A path is little more than a habit that comes with knowledge of a place. It is a sort of ritual of familiarity.

A road, on the other hand, even the most primitive road, embodies a resistance against the landscape. Its reason is not simply the necessity for movement, but haste.

One has made a relationship with the landscape, and the form and the symbol and the enactment of the relationship is the path.

We have lived by the assumption that what was good for us would be good for the world. And this has been based on the even flimsier assumption that we could know with any certainty what was good even for us.

We have been wrong. We must change our lives, so that it will be possible to live by the contrary assumption that what is good for the world will be good for us.

And that requires that we make the effort to know the world and to learn what is good for it.

The most exemplary nature is that of the topsoil. It is very Christ-like in its passivity and beneficence, and in the penetrating energy that issues out of its peaceableness. It increases by experience, by the passage of seasons over it, growth rising out of it and returning to it, not by ambition or aggressiveness. It is enriched by all things that die and enter into it. It keeps the past, not as history or as memory, but as richness, new possibility. Its fertility is always building up out of death into promise. Death is the bridge or the tunnel by which its past enters its future.

There can be disembodied thought, but not disembodied action.

And we will have to give up a significant amount of scientific objectivity, too. That is because the standards required to measure the qualities of farming are not just scientific or economic or social or cultural, but all of those, employed all together.

This line of questioning finally must encounter such issues as preference, taste, and appearance. What kind of farming and what kind of food do you like? How should a good steak or tomato taste? What does a good farm or good crop look like? Is this farm landscape healthful enough? Is it beautiful enough? Are health and beauty, as applied to landscapes, synonymous? With

In our limitless selfishness, we have tried to define ‘freedom,’ for example, as an escape from all restraint. But, as my friend Bert Hornback has explained in his book The Wisdom in Words, ‘free’ is etymologically related to ‘friend.’ These words come from the same Germanic and Sanskrit roots, which carry the sense of ‘dear’ or ‘beloved.’* We set our friends free by our love for them, with the implied restraints of faithfulness or loyalty. This suggests that our ‘identity’ is located not in the impulse of selfhood but in deliberately maintained connections. Thinking

Perhaps our most serious cultural loss in recent centuries is the knowledge that some things, though limited, can be inexhaustible. For example, an ecosystem, even that of a working forest or farm, so long as it remains ecologically intact, is inexhaustible. A small place, as I know from my own experience, can provide opportunities of work and learning, and a fund of beauty, solace, and pleasure – in addition to its difficulties – that cannot be exhausted in a lifetime or in generations.

For an art does not propose to enlarge itself by limitless extension, but rather to enrich itself within bounds that are accepted prior to the work.

Within these limits artists achieve elaborations of pattern, of sustaining relationships of parts with one another and with the whole, that may be astonishingly complex. Probably most of us can name a painting, a piece of music, a poem or play or story that still grows in meaning and remains fresh after many years of familiarity.

But in the arts there are no second chances. We must assume that we had one chance each for The Divine Comedy and King Lear. If Dante and Shakespeare had died before they wrote those poems, nobody ever would have written them.

To the conservation movement, it is only production that causes environmental degradation; the consumption that supports the production is rarely acknowledged to be at fault.

It is odd that simply because of its ‘sexual freedom’ our time should be considered extraordinarily physical. In fact, our ‘sexual revolution’ is mostly an industrial phenomenon, in which the body is used as an idea of pleasure or a pleasure machine with the aim of ‘freeing’ natural pleasure from natural consequence. Like any other industrial enterprise, industrial sexuality seeks to conquer nature by exploiting it and ignoring the consequences, by denying any connection between nature and spirit or body and soul, and by evading social responsibility. The spiritual, physical, and economic

...more

As is often so, it was only after family life and family work became (allegedly) unnecessary that we began to think of them as ‘ideals.’

I do think that the ideal is more difficult now than it was. We are trying to uphold it now mainly by will, without much help from necessity, and with no help at all from custom or public value.

parenthood is not an exact science, but a vexed privilege and a blessed trial, absolutely necessary and not altogether possible.

If we make our house a household instead of a motel, provide healthy nourishment for mind and body, enforce moral distinctions and restraints, teach essential skills and disciplines and require their use, there is no certainty that we are providing our children a ‘better life’ that they will embrace wholeheartedly during childhood. But we are providing them a choice that they may make intelligently as adults.

To refuse to admit decent and harmless pleasures freely into one’s own life is as wrong as to deny them to someone else. It impoverishes and darkens the world.

A picked cornfield under a few inches of water must be the duck Utopia – Utopia being, I assume, more often achieved by ducks than by men.