More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

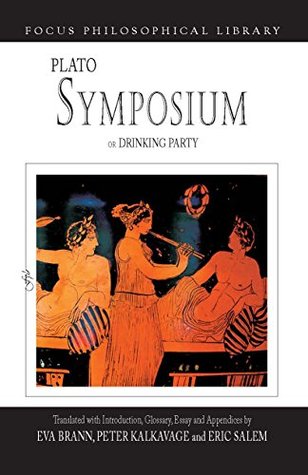

The reader must imagine, as the characters deliver their love-speeches, that they do so not from a standing position but {xv} reclining on couches, leaning on the left elbow with the right hand free to do whatever. •

I recently came across a wise man’s book in which salt received wondrous praise for its usefulness, |C| and you could see many other such things being celebrated. Just think: to be so serious about such things, while to this day no human being has yet ventured to make a worthy hymn to Love, Eros

For medicine, to sum it up, is knowledge of love-matters pertaining to the body relative to filling up and emptying out. And he who in his diagnosis can distinguish in these matters between |D| the noble and the base love—this is the one who is supremely skilled in medicine;

First, there were three kinds of humans—not two, as there are now, male and female, |E| but in addition a third, which had a share in both of these, and of which the name alone is left over, while the kind itself has disappeared. For at that time one kind was man-woman, sharing in form as well as name in both male and female, but now it exists as nothing but a name used in reproach.

Second, the form of each human was wholly round, with its back and sides in a circle, and it used to have four hands, and legs equal in number to the hands, |190A| and two faces, alike in every way, on a cylindrical neck. There was one head for both faces, which were placed opposite each other, and four ears and two private parts, and all else, as one might imagine, in accord with these. And just as now, it traveled upright in whatever direction it might wish. And whenever they would set out to run fast, just as tumblers tumble in a circle with their legs stuck straight out, they too, by

...more

What I shall now do to them is cut each in two, so they’ll at once be weaker and, because of their greater numbers, more useful to us. And they’ll walk upright upon two legs.

So Apollo would turn the face around, and drawing the skin from everywhere over what is now called the belly (just as in pouches with a drawstring), he left one inlet and tied it off in the middle of the belly, and that is what they now call the navel.

Now when its nature had been sliced in two, each slice, yearning for its own half, came together with its other; and throwing their arms around each other and entwining themselves with each other in their desire to grow together again, they kept dying off from hunger |B| and from other forms of inactivity because they were unwilling to do anything apart from each other.

from such early times human beings |D| have had Love for one another inborn in them—Love, reassembler of our ancient nature, who tries to make one out of two and to heal human nature.

“Now it’s been agreed, hasn’t it, that one loves that which one is in need of and does not have?” “Yes,” he said. “Therefore, Love is in need of and does not have beauty?” “It’s a necessity,” he declared. “What about this? Do you claim that what is in need of beauty and never possesses beauty is beautiful?” “Certainly not.” “Then if this is the case, do you still agree that Love is beautiful?”

Love at no time either is resourceless or is wealthy; and moreover, he’s in the middle between wisdom and ignorance.

Socrates is standing in the neighbor’s porch and not responding when called. Agathon wants to compel Socrates to come in, but Aristodemus stops him, explaining that for Socrates this is normal behavior (175B). The explanation points to a major theme in the Symposium: the odd ways of the philosopher, who sometimes unaccountably stops to think and seems to go off into his own world.92 This is indeed a cause for wonder. But it’s also a reproach to mere mortals, especially ambitious ones {65} like Alcibiades, who are bent on moving forward with no thought about where they’re going.

Take time to think about how and why you're living and doing what you do and abput anything in existance or nonexistance

no Athenian would put up with someone who begged and pleaded for money and power, but lovers can get away with begging, pleading and even breaking their promises, as long as they do it in the name of Love

Having made the descent into Agathon’s house of phantom speech in praise of what he claims to know best—love-matters—Socrates comes away unscathed and in full possession of himself. He ascends from Hades and, in more than one sense, goes back home.