More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

They will vanish all at the same time, like the millions of images that lay behind the foreheads of the grandparents, dead for half a century, and of the parents, also dead. Images in which we appeared as a little girl in the midst of beings who died before we were born,

“Out of extreme narcissism, I want to see my past set down on paper and in that way, be as I am not” and “There’s a certain image of women that torments me. Maybe orient myself in that direction.” In a Dorothea Tanning painting she saw in a show three years before in Paris, a bare-chested woman stands before a row of doors that stand ajar. The title was Birthday. She thinks this painting represents her life and that she is inside it, as she was once inside Gone with the Wind, Jane Eyre, and later Nausea.

During that summer of 1980, her youth seems to her an endless light-filled space whose every corner she occupies. She embraces it whole with the eyes of the present and discerns nothing specific. That this world is now behind her is a shock.

She feels as if a book is writing itself just behind her; all she has to do is live. But there is nothing.

She pictures herself here in ten or fifteen years with a cart filled with sweets and toys for grandchildren not yet born. But she sees that woman as improbable, just as the girl of twenty-five saw the woman of forty, whom she has since become and already ceased to be.

As the time ahead objectively decreases, the time behind her stretches farther and farther back, to long before birth, and ahead to a time after her death.

She is afraid that as she ages her memory will become cloudy and silent, as it was in her first years of life, which she won’t remember anymore.

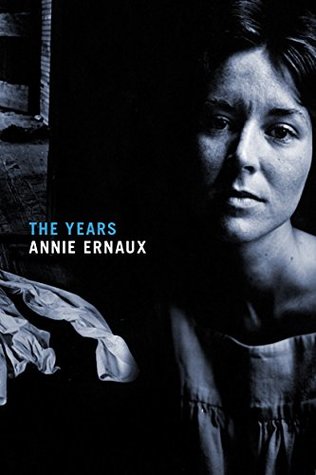

To this “incessantly not-she” of photos will correspond, in mirror image, the “she” of writing.