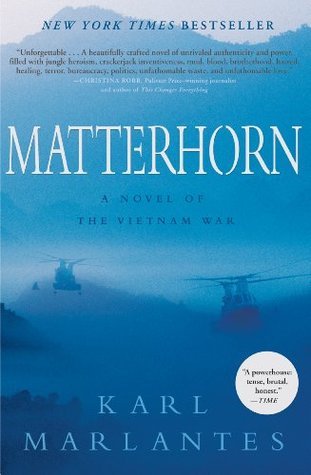

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Victory in combat is like sex with a prostitute. For a moment you forget everything in the sudden physical rush, but then you have to pay your money to the woman showing you the door. You see the dirt on the walls and your sorry image in the mirror.

“Just wait a while,” Mellas said. “They were on our side twenty-five years ago.” “No shit. Who switched sides, us or them?” “I think it was us. We used to be against colonialism. Now we’re against communism.”

God had given him life and must have laughed as Mellas used it to kill Pollini, to get a piece of ribbon to show proof of his worth. And it was his worth that was the joke. He was nothing but a collection of empty events that would end as a faded photograph above his parents’ fireplace.

And in that cursing Mellas for the first time really talked with his God.

Mellas wondered if it had eventually been like this in the concentration camps. Had they reached the point where horror had no force?

Fitch pulled the company into the smaller circle of holes. There were no longer enough Marines to defend the outer perimeter. Mellas tried to ease the pain in his throat and tongue by licking the dew on his rifle barrel. It didn’t work.

I’m a racist too. You can’t grow up in America and not be a racist. Everyone on this fucking hill’s a racist and everyone back in the world’s a racist. Only there’s one big difference between us two racists you can’t ever change and I can’t ever change.” “What’s that?” Mellas asked. “Being racist helps you and it hurts me.”

We won’t be free of racism until my black skin sends the same signals as Hawke’s red mustache.

He ran as he’d never run before, with neither hope nor despair. He ran because the world was divided into opposites and his side had already been chosen for him, his only choice being whether or not to play his part with heart and courage.

He ran because his self-respect required it. He ran because he loved his friends and this was the only thing he could do to end the madness that was killing and maiming them.

Mellas now knew, with utter certainty, that the North Vietnamese would never quit. They would continue the war until they were annihilated, and he did not have the will to do what that would require. He stood there, looking at the waste.

He thought of the jungle, already regrowing around him to cover the scars they had created. He thought of the tiger, killing to eat. Was that evil? And ants? They killed. No, the jungle wasn’t evil. It was indifferent. So, too, was the world. Evil, then, must be the negation of something man had added to the world. Ultimately, it was caring about something that made the world liable to evil.

Being human was the best he could do. Without man there would be no evil. But there was also no good, nothing moral built over the world of fact. Humans were responsible for it all. He laughed at the cosmic joke, but he felt heartsick.

Revenge would heal nothing. Revenge had no past. It only started things. It only created more waste, more loss, and he knew that the waste and loss of this night could never be redeemed. There was no filling the holes of death. The emptiness might be filled up by other things over the years—new friends, children, new tasks—but the holes would remain.

Mellas longed to go out on patrol, back to the purity and green vitality of the jungle, where death made sense as part of the ordered cycle in which it occurred, in the dispassionate search for food that involved loss of life in order to sustain life.

The jungle and death were the only clean things in the war.

shadows: the chanters, the dead, the living. All shadows, moving across this landscape of mountains and valleys, changing the pattern of things as they moved but leaving nothing changed when they left. Only the shadows themselves could change.