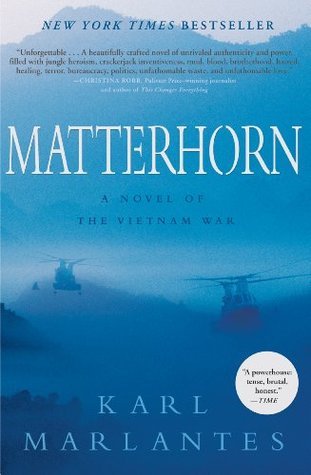

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

It overwhelmed him. From the skipper right on down, they all wore the same filthy tattered camouflage, with no rank insignia, no way of distinguishing them. All of them were too thin, too young, and too exhausted.

They all talked the same, too, saying fuck, or some adjective, noun, or adverb with fuck in it, every four words. Most of the intervening three words of their conversations dealt with unhappiness about food, mail, time in the bush, and girls they had left behind in high school. Mellas swore he’d succumb to none of it.

“Oh, a couple of numbnuts bitch a lot and keep things stirred up. Out here the splibs can’t bitch any more than the chucks. We’re all fucking niggers as far as I can tell.”

Invisible rain struck his cheeks. The warmth from his poncho liner drifted away like a thin cry over stormy water.

They carried Kool-Aid packages, Tang—anything to kill the chemical taste of the water in their plastic canteens. Soon the smears of purple and orange Kool-Aid on their lips combined with the fear in their eyes to make them look like children returning from a birthday party at which the hostess had shown horror films.

“Sorry,” Mellas said. Hawke visibly softened. He handed up the steaming cup and smiled. “Shit, Mellas, drink this. It cures all ills, even vainglory and ambition. The only thing that hurts about a rebuke is the truth.”

“Just one more glorious day in the corps,” said Bass, “where every day’s a holiday and every meal’s a feast.” “Lifer,” Fredrickson retorted. “Loyal, industrious, freedom-loving, efficient, rugged,” Bass shot back quickly.

“Lazy, ignorant fucker expecting retirement,” Fredrickson replied. Mellas burst out laughing. “No fucking comments from the junior officer section,” Bass said.

“So, gentlemen,” the colonel went on, “I’d like to propose a toast to the best goddamned fighting battalion in Vietnam today. Here’s to the Tigers of Tarawa, the Frozen Chosen of Chosin Reservoir. Here’s to

the First Battalion Twenty-Fourth Marines.”

It was well known that Arran had extended his tour twice because the scout dogs couldn’t be transferred to other handlers, and when their tour was over, they were killed. Someone back in the world had declared them too dangerous to bring home.

“May you be ten minutes in heaven before the devil knows you’re gone,” Simpson said, raising his glass and gulping a large swallow.

Mellas was transported outside himself, beyond himself. It was as if his mind watched everything coolly while his body raced wildly with passion and fear. He was frightened beyond any fear he had ever known. But this brilliant and intense fear, this terrible here and now, combined with the crucial significance of every movement of his body, pushed him over a barrier whose existence he had not known about until this moment. He gave himself over completely to the god of war within him.

Victory in combat is like sex with a prostitute. For a moment you forget everything in the sudden physical rush, but then you have to pay your money to the woman showing you the door. You see the dirt on the walls and your sorry image in the mirror.

He also understood that his participation in evil, was a result of being human. Being human was the best he could do. Without man there would be no evil. But there was also no good, nothing moral built over the world of fact. Humans were responsible for it all. He laughed at the cosmic joke, but he felt heartsick.

“Between the emotion and the response, the desire and the spasm, falls the shadow,” Mellas said. He attempted a smile.

Emotion constricted Hawke’s throat. He suddenly understood why the victims of concentration camps had walked quietly to the gas chambers. In the face of horror and insanity, it was the one human thing to do. Not the noble thing, not the heroic thing—the human thing. To live, succumbing to the insanity, was the ultimate loss of pride.

Revenge would heal nothing. Revenge had no past. It only started things. It only created more waste, more loss, and he knew that the waste and loss of this night could never be redeemed. There was no filling the holes of death. The emptiness might be filled up by other things over the years—new friends, children, new tasks—but the holes would remain.

What he did and thought in the present would give him the answer, so he would not look for answers in the past or future. Painful events would always be painful. The dead are dead, forever.

He knew that all of them were shadows: the chanters, the dead, the living. All shadows, moving across this landscape of mountains and valleys, changing the pattern of things as they moved but leaving nothing changed when they left. Only the shadows themselves could change.