More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

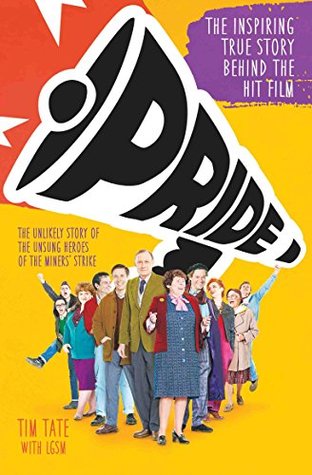

Tim Tate

Read between

August 26 - August 27, 2018

At Leeds, I helped set up Leeds Gay Switchboard on university property. But we had to do it under the guise of running a science-fiction library. As far as the university authorities were concerned, we were running a sci-fi library.

The Falklands War was the big turning point for us – especially in this part of Wales. More than a hundred years before, a group of people had left the valleys and gone to Patagonia in Argentina, where they set up a Welsh-speaking community. That community thrived and, when the war happened, we knew that some of the young soldiers fighting for Argentina would be called David Jones, or whatever: they might speak Welsh with a Spanish accent but they still spoke Welsh. So how could they be the enemy? On top of that, much of the Falklands was owned or managed by British coal companies – and we saw

...more

Sometimes they’d stop you, search the car and ask who was travelling with you – and even which party you’d voted for in the previous general election. There were stories of people’s houses being raided in the middle of the night on suspicion of sheltering flying pickets.

When we moved on to the roundabout just outside the steelworks, to shout at the lorries coming out through the picket lines, there was this young policeman and I saw that his knuckles were white with rage: he was struggling to control his temper. But you know how it made me feel? Proud. And I thought to myself, ‘There’s not many “rabble” who have a degree in physics, is there?’

I always used to say that there was a poison dwarf sitting in the corner of every one of our living rooms. It was television: a poison dwarf spewing out all these things. And suddenly, we were watching TV in a very different way. We were having to rely on the media for what was happening in other coalfields and we were realising that it didn’t reflect anything that was happening;

I know this is contentious but I felt that Cardiff was waiting for the new service and financial economy; that Wales didn’t need manufacturing any more.

Of course, we hoped for a response of some kind but we kind of thought they’d say, ‘Oh, thanks very much – now fuck off, you pansies.’

The important thing we had learned was that, if we were being vilified, if we were being denigrated and if the State was calling us ‘the enemy within’, what did that say about all these other people who, we’d been told for years, were also the enemy within? Perhaps they were just like us. Perhaps they were being unfairly treated. Perhaps they were being lied about. And our perception changed dramatically.

Paul O’Grady [Lily Savage’s alter ego] had seen me shaking the bucket outside a couple of times: he always gave money and offered a few words of comfort, but could see that the collections weren’t raising a huge amount of money. And so on two or three occasions, he wouldn’t let anyone leave the bar until they put money in the bucket. And the collection went from four quid to twenty-five quid on those nights because everyone was absolutely terrified of Lily. I certainly was: there weren’t that many things that frightened me then but Lily Savage was one of them.

For anyone thinking it was remarkable that we had gay people coming down here, well, what was remarkable to me was that we had communities from three different valleys here and they were talking to one another.

The Sun promptly congratulated the council, proclaiming that it was time to stop the ‘sick nonsense’ of gay rights: ‘Let’s ALL follow Rugby in fighting back.’

MIKE JACKSON What was so wonderful for me on that very first visit was that all these people knew about us was that we were lesbians and gay men, and we supported them in their strike. All I ever wanted was acceptance, and here it was, in bucketloads, in this Welsh miners’ welfare club.

I wasn’t expecting them to be as cultured, as outward looking and as aware as I found them. Because they were aware of the outside world: they were happy in theirs but they had developed an awareness that I, in my bigoted mind, hadn’t credited them with before I arrived.

Within weeks, the Sun published a demand, by American psychologist Paul Cameron, that ‘all homosexuals should be exterminated to stop the spread of AIDS. We ought to stop pussyfooting around.’

My phone was definitely tapped. There were clicks on the line and, on occasion, an official in the union office picked up his phone only to hear a tape recording playing of one of his colleagues who was speaking in the next-door office: there was his voice coming down the phone. And there were telephone engineers outside my house always – all the bloody time.

On the day the men went back, I was working in a local shirt factory. Many of the miners’ wives had worked there and, throughout the strike, they had worked long hours there to keep families going. But the managers had kept putting the targets up, just to take advantage of these desperate women. The women couldn’t hit these targets so they didn’t get their full bonuses, and the managers used to revel in the fact that they were doing this, upping the targets. So many of the women were glad, in one way, that their men were going back to work.

I used to say that the strike was like a fast track to find out anything you wanted to find out about, politically.

I absolutely believe that the arrival of LGSM in our valleys changed those communities. It’s not often you meet twenty-five people in one room and you like every single one. They were generous, kind-hearted, articulate, intelligent: how could I not like them?

Public opinion was poisoned by regular and vicious anti-gay features in the tabloid press. A column in the Daily Star that year, written by its deputy editor, Ray Mills, was typical: Little queers or big queens, Mills has had enough of them all – the lesbians, bisexuals and transsexuals, the hermaphrodites and the catamites and the gender benders who brazenly flaunt their sexual failings to the disgust and grave offence of the silent majority. A blight on them all, says Mills.

But Mrs Thatcher and other Conservative politicians opposed any spending on health advice. The country’s only HIV/AIDS-specific organisation – the Terrence Higgins Trust – had been established in 1983 but, for the first two years of its life, it was entirely dependent on charitable donations. When the GLC stepped in with £17,000 of urgently needed support, the Conservative-led Westminster Council went to court to block the grant.

During the May 1986 local elections, for example, Conservatives in the London Borough of Haringey produced a leaflet declaring, ‘You do not want your child to be educated by a homosexual or lesbian.’

In December 1987 the offices of Capital Gay were firebombed. In Parliament, Conservative MP Elaine Kellett-Bowman unashamedly welcomed the news: ‘Quite right! … I am quite prepared to affirm that there should be an intolerance of evil!’

JONATHAN BLAKE At that point, HIV and AIDS were only attacking homosexuals and they were deemed expendable. I mean, who cared about us? That was the attitude: who cares? The only reason that changed was because of the health minister Norman Fowler, who is the one person, among all the Tories, that I do have any time for. He told Margaret Thatcher that it was in the heterosexual community and she freaked. What he didn’t tell her was that this was the intravenous heterosexual drug-using community of Edinburgh. Because if she’d have known that, she’d have said, ‘Let ’em die.’ But because HIV and

...more

MIKE JACKSON I think the film struck a chord. I don’t think it could have been made ten or twenty years ago. And, ironically, we’re now in a situation where we have a government which is worse than Thatcherism. It is naked, blatant, arrogant and cruel. And I think the film came out at a time when people were really frustrated and angry and didn’t know what to do. Pride showed that grassroots activism – forget the party apparatchiks and the media – can make difference. And that’s really heartening.

DAVE LEWIS The people who control London Pride now get really excited about the fact that they’ve got the Red Arrows flying over Trafalgar Square. I’m outraged by that. They think that the battles have all been won – and I disagree with that wholeheartedly.

Not since the tumultuous year of 1984–85 has the world been so divided by hatred, or seemed so volatile and so threatening. However ugly, however ill-reasoned, some of the anger and division of these past twelve months is a much-delayed reaction to the price we are continuing to pay for Mrs Thatcher’s free-market economics and the decades of casino capitalism which followed.