More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Ahdaf Soueif

Read between

January 21 - February 6, 2024

there was a message from An-Najah University in Nablus inviting me to go and read there. Nablus is only thirty-six kilometres north of Ramallah, but the city had been under Israeli closure for three years. Not a problem, said the university; we’ll send someone to get you. They sent a Samaritan in a white minivan who took us also to visit his home in Mount Gerizim. He showed us pictures of himself in traditional Syrian dress. The Samaritans self-identify as ‘Palestinian Jews’ and carry both Israeli and Palestinian documents. Israeli checkpoints open for them.

In Palestine almost every situation you can be in is layered. Nothing, not a single thing, is free of the occupation, its instruments, its outcomes.

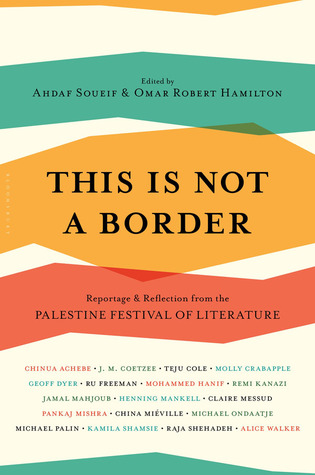

Over ten years PalFest brought to Palestine some of the finest English-language novelists, essayists, dramatists and poets. We also brought publishers, agents and cultural producers. Their brief was to conduct literary events, workshops and seminars, to network, to scout for new talent; for one week they would meet and interact with Palestinians on their home ground. This book – marking PalFest’s tenth anniversary – contains some of the writings that were born out of this undertaking.

Israel has never agreed to an official delineation of its borders. However, it controls all access routes into historic Palestine. So even though the bridge connects Jordan to the occupied Palestinian territories, it is under Israeli – rather than Palestinian Authority – control and is the first point at which the visitor is subject to Israeli procedures. And so it makes an appearance in many of the pieces in this book.

An aspect of the occupation that is quite difficult for non-locals to get their heads around is that the majority of the barriers – the wall and the checkpoints in their varied manifestations – are not in fact borders; they do not separate ‘Palestine’ from ‘Israel’; mostly they cut through occupied Palestinian land, separating communities from each other, from their land, from their markets, their universities, their schools.

There are fast roads built for the convenience of Israeli settlers who live in the occupied areas in violation of international law,

‘Certainly in writing and speaking, one’s aim is . . . trying to induce a change in the moral climate whereby aggression is seen as such, the unjust punishment of peoples or individuals is either prevented or given up, and the recognition of rights and democratic freedoms is established as a norm for everyone, not invidiously for a select few.’

This war that Israel wages against us is not a war to defend its existence, but a war to obliterate ours.

Yesterday, we celebrated the end of apartheid in South Africa. Today, you see apartheid blossoming here most efficiently. Yesterday, we celebrated the fall of the Berlin Wall. Today, you see the wall rising again, coiling itself like a giant snake around our necks. A wall not to separate Palestinians from Israelis, but to separate Palestinians from themselves and from any view of the horizon. Not to separate history from myth, but to weld together history and myth with a racist ingenuity.

Life here, as you see, is not a given, it’s a daily miracle.

Life here is less than life, it is an approaching death.

Here, on this slice of historic Palestine, two generations of Palestinians have been born and raised under occupation. They have never known another – normal – life. Their memories are filled with images of hell. They see their tomorrows slipping out of their reach. And though it seems to them that everything outside this reality is heaven, yet they do not want to go to that heaven. They stay because they are afflicted with hope.

I know that this is not exactly the source of my hesitation. It’s the word Palestine. But what else could I call it? The Territories? The West Bank? Do I need to hide it, the way I hide it at the Allenby Bridge crossing? Do I need to soften it for this audience by placing it next to the word Israel? Can a word be made so absent without people becoming alarmed when it does appear?

What else are we hiding when we hide Palestine?

Most people don’t know that Gaza and the West Bank are as unreachable from one another as two places can be. You cannot reach either one without going through a border or a checkpoint controlled by Israel. Sometimes you can reach Gaza by going through Egypt, Israel’s ally in its siege. You cannot be in Palestine without saying your grandfather’s name to Israeli officials at the border or the airport. You cannot eat in Palestine without buying or dodging Israeli products. You cannot buy anything at all without using Israeli currency. In Palestine, Israel is everywhere.

A week after the festival has wrapped a drunk man in Ramallah says, Don’t be enchanted by Haifa. Haifa is corrupt, her beauty is a cheap mask. Go to the abandoned villages, go to the Muthallath, go to Um el-Fahm; there you will find Palestine.

When a house gets demolished in East Jerusalem, does it stop being Palestine? When, in which moment? When the first brick drops or when the last is cleared?

perhaps the role of literature and art should be to look for what is hidden, what is obscured, what is made harder and harder to reach.

each day jihad each day faith over fear each day a mirror of fire the living want to die with their families

The Palestinians say that the Israelis in East Jerusalem have moved from the phase of i7tilal to that of i7lal. We can deal with them living here alongside us, they say, but they want to live here instead of us.

‘One of the most pleasant features of the al-Aqsa Sanctuary is that wherever a person sits within it, they will feel that they have found the best position with the best view,’

Settlers sometimes fight and sometimes kill and sometimes burn. And Israel cleans up after them. When Baruch Goldstein, a settler, went into the Ibrahimi Mosque in al-Khalil/Hebron on 25 February 1994 and killed twenty-nine Muslim men at prayer – then was himself killed by the congregation, Israel divided the mosque and made the larger half of it over to the settlers for Jewish prayers. A shrine for the ‘martyr’ Dr Goldstein was established near it, and Israel’s military presence in the heart of the city and around the mosque was permanently intensified.

Every day Israel kills at least one Palestinian. Every day it arrests and detains and interrogates and demolishes.

Sometimes a young Palestinian wakes up in the morning and takes a knife from her mother’s kitchen and goes out to mount a solitary, hopeless attack on Israeli soldiers. Sometimes Israeli soldiers kill a young Palestinian and toss a knife onto the ground next to him. The language of justice and decency is no longer relevant. The language of human rights is bitter. The language of red heifers and crimson worms and red heifers and cable cars and crimson worms and holy package tours is swelling. Here. Here in the heart of the world that will burst. Soon.

‘I wish that I could offer you such a banquet, but I have never seen the sea. So I offer what I have.’

At Odai’s grave, in a small cemetery at the edge of the camp, an extraordinary transposal occurs. I am frozen to the spot, crying. Mohammad puts his arms around me and consoles me. ‘I understand your grief, you are somebody’s mother.’

This time I had arrived at Hebron after a very different journey, one that took me both deeply into my Jewish culture and showed it to me from the other side of the mirror, so to speak, challenging many of my previous assumptions.

Several times during the trip the quality of the psychological power exerted by the structures and procedures of checkpoints reminded me of immersive works of art, installations or promenade theatre pieces designed to have a strong emotional effect, to make manifest the conceptual relations of power, of individual and state.

Now I found myself in the east, a grown adult meeting many Palestinians, and felt in that environment no sense of threat whatsoever. The fear that I was carrying melted away; my body relaxed, my breathing slowed and deepened. The sensation was of lightness and elation; it was born from a revelation that’s so obvious, so bound to be true, I’m almost ashamed to admit it: Palestinians are normal people – friendly, intelligent, rational people. Not only that, their warmth and openness, given their situation, was very striking. All the Palestinians we met were extraordinarily hospitable and pleased

...more

More than a generation of West Bank Palestinians now exist who have never seen the sea.

At Hawara, the most notorious of the checkpoints, a number of deaths have been recorded of people waiting to get through for medical treatment.

There is an Israeli law that land ‘abandoned’ for seven years becomes the property of the state. The inhabitants of Bethlehem wait powerlessly for the land they have farmed continuously for centuries to be taken from them. You wonder what it does to the children who are growing up behind that wall, which exists, they are told, because they are so dangerous, and who see the only real power in the town wielded by visiting soldiers with machine guns.

The illegal settlements are the other great lesson of the occupied territories. There are a huge number of them, instantly recognisable by their bare, prefabricated ugliness and position, placed and fortified on the tops of hills, disfiguring the landscape their inhabitants claim to love with all the aesthetic indifference of true religious fundamentalism.

I find that the settlers’ Judaism is both very difficult and worryingly easy to understand. It bears very little relation to the tolerant, intellectual, profoundly moral Judaism I am proud to have grown up in, a tradition that is acutely aware of its outsider status and therefore highly sensitive to the vulnerabilities of other communities. Settler Judaism is something else altogether: messianic, fundamentalist, indifferent to pain, soaked in violence. But it arises from tropes well within the Jewish tradition. Its claim on the land is there in the Torah, a land that, after all, is promised to

...more

An Israeli voice came to mind, the imperturbable reasonableness of government spokesman Mark Regev, often heard on Radio 4’s Today programme. It is a voice I’d empathised with and wanted to trust. Seeing the flatly contradictory facts on the ground, its even tone was revealed to me as the sound of a propaganda machine.

I felt great anguish at the unnecessary suffering of the Palestinians and anger on my own behalf, but also on behalf of all the loving, reasonable, humane Jews I know and love in the diaspora who have been beguiled by understandable fear for Jewish survival and an admirable solidarity with the people of Israel into supporting the insupportable.

Hebron is one place we saw the infamous division of different roads into those for settler usage and Palestinian usage that gives rise to talk of apartheid. Whether you agree with the use of that term or not, there is a technical sense in which it is very hard to disavow. Illegal settlers living in Palestinian territory do so under Israeli civil law. Palestinians in the same territory live under an accumulation of more than 1,500 military orders. Two populations in the same place under two different legal systems determined by their ethnicity. Clearly this fulfils the very definition of

...more

Many years after that historical tragedy we are beset by questions of how the wider population could have tolerated the actions of its government or the minority of ideological extremists, how complicit they were, why they didn’t say anything, how much they knew and how possible it was not to know. I am hugely grateful that such questions regarding the Palestinian situation have been settled for me. I have seen and I know. Now, like many thousands of other Jews in Israel and around the world, I protest.

I watch now from afar, from those two heavy red marks, as foreigners with massive guns continue to claim the terrain of my ancestral home. An American-born man of Polish ancestry whose family changed its name from Mileikowsky to Netanyahu sits at the helm as prime minister. A former Russian bar bouncer named Avigdor Lieberman oversees the oppression of four million Palestinians trapped in isolated, heavily surveilled ghettos. Naftali Bennett, whose family came from San Francisco, is a high-ranking politician and minister of education committed to the destruction of Jerusalem’s golden Dome of

...more

These foreigners, with absolutely no identifiable ancestry in the land, believe it is their right to remove us and take our place. To erase us and make our heritage their own. To destroy our monuments, cemeteries and history. To live in my grandmother’s ancient home and pretend that the stories of those like Mohammad Khalil are their own. Because God chose them. Because God loves them more.

Occupation, he wrote, ‘interferes in every aspect of life and of death; it interferes with longing and anger and desire and walking in the street. It interferes with going anywhere and coming back, with going to market, the emergency hospital, the beach, the bedroom, or a distant capital.’

For crossing the Allenby Bridge, the sole designated entry/exit point for West Bank Palestinians, is one of the most exasperating experiences. If anything, Israel should be given a prize for putting in place and in practice one of the most Byzantine systems of control ever.

Considering that 900 out of the 14,000 passengers who crossed the bridge daily during the month of July used the VIP service, one concludes that Palestinians like myself are contributing close to $50 million annually to the financing of our own occupation!

More significantly though, this was the most friendly – overfriendly, awkwardly friendly – encounter I have ever had with Israelis, anywhere, in the long decades I’ve lived under occupation. It is hard to explain the unease and the discomfort my husband and I felt on being treated respectfully and humanely by Israelis.

One last thought comes to mind: if the Israeli Border Authorities can take pride in handling sixteen million passengers a year at Tel Aviv Airport, why can’t they handle one tenth of that number on the Allenby Bridge? I can only come to one conclusion.

What becomes less immediate when you are far away from the turnstiles and the teenage soldiers with their guns and braces is remembering the rage that flows from being so regularly trapped and humiliated, and being powerless to do anything to make it stop.

You can always tell a Palestinian home by the water tanks on the roofs. Israelis don’t need them. The settlers consume an average 350 litres a day, the Palestinians just 60 litres.

The West Bank is about the ‘enemy within’. Turn 360 degrees and you will see the omnipresence of Israel in Palestine. A watchtower, the dreaded wall, a barbed-wire fence, a settlement, soldiers, tanks, hideous little flags and whatever other affront they impose. Gaza is the ‘enemy without’; unseen. It’s the biggest concentration camp in the world, where no one has any freedom of movement in or out of the country and unemployment approaches 50 per cent.

There are so many stories that they begin to appear unbelievable. They should be. When I return home after just one week I am emotionally drained. When I try to describe the situation and what I have seen and heard, I cry. The Palestinians do not cry. This is their life, and they lead it with courage, dignity and hope. One day, waiting at the Qalandia checkpoint, I watched a little bird hopping either side of a barbed-wire fence, eventually to fly off to its own freedom. What a thought.

The drive to Jerusalem was a total shock: I had been imagining ‘settlements’ as small beleaguered outposts on the tops of some hills – but in fact they are huge towns with high-rise buildings that cover every single hilltop, all running into each other to make one vast urban sprawl dominating the country. Why don’t we all know this? It seems like an incredibly well-guarded secret – I wish everyone could come here and see what is going on. As for the idea of demolishing any of them – dream on. No one is going to be able to dismantle any of these illegal towns. Maybe the most alien thing about

...more