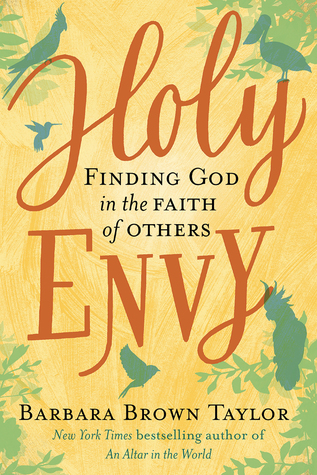

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

November 24 - December 2, 2021

Sometimes, on the last day of class, I hand out cards with versions of the Golden Rule on them. “Hurt not others in ways that you yourself would find hurtful.” That one is from Judaism. “None of you is a believer until you love for your brother what you love for yourself.” That one is from Islam. “This is the sum of duty: do not do to others what would cause pain if done to you.” That one is from Hinduism. Some version of the principle shows up in all the great religions of the world, which is a large part of what makes them great: they ask members inside the tribe to use their humanity as the

...more

Raimon Panikkar, another renowned scholar of religion who was also a Catholic priest, spent a lot of time thinking about what it might mean for Christians to focus on contributing to the world’s faiths instead of dominating them. Born in Spain to a Catholic mother and a Hindu father, he used the analogy of the world’s great rivers. The Jordan, the Tiber, and the Ganges all nourish the lives of those who live along their banks, he said. One flows through Israel, one flows through Rome, and one flows through India. If he were writing today he might have added the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers,

...more

For reasons that will never be entirely clear, God sometimes sends people from outside a faith community to bless those inside of it. It does not seem to matter if the main characters understand God in the same way or call God by the same name. The divine blessing is effective, and the story goes on.

However you define the problematic present-day stranger—the religious stranger, the cultural stranger, the transgendered stranger, the homeless stranger—scripture’s wildly impractical solution is to love the stranger as the self. You are to offer the stranger food and clothing, to guarantee the stranger justice, to treat the stranger like one of your own citizens, to welcome the stranger as Christ in disguise. This is God’s express will in both testaments of the Bible.

They were furious because he had taken a swing at their sense of divine privilege—and he had used their own scriptures to do it.

“If you have striven to know God for a decade or more,” she writes, “you are almost certain to cross a spiritual wasteland, which ranges from dryness and boredom to agony and abandonment.” Anyone who has read the classics of the Christian spiritual life recognizes this wilderness as a predictable stop on the journey into God. Augustine’s Confessions, Teresa of Ávila’s Interior Castle, and John of the Cross’s Dark Night of the Soul all talk about it. As variously as people describe it, they all discover that if you are determined to walk the way of Jesus, there comes a time when you must leave

...more

our mainline Christian lives are not particularly compelling these days. There is nothing about us that makes people want to know where we are getting our water. Our rose has lost its fragrance. The students in my class may be failing Christianity, but Christianity is failing them too. If the Spirit is doing a new thing, I wish it would hurry up. Or maybe this is the new thing—a smaller, more humble version of church with less property and fewer clergy pensions; an odd collection of people meeting here and there as they try to figure out what it means to follow Jesus in a world of many faiths;

...more

“You do not know,” Jesus says. Not because you are stupid, but because you are not God. So relax if you can, because you are not doing anything wrong. This is what it means to be human.

Thanks to his conversation with Nicodemus, I gained new respect for what it means to be agnostic—such a maligned word, so often used to mean distrustful or lackadaisical, when all it really means is that you do not know, which according to Jesus is true of everyone who is born of the Spirit.

line from Maya Angelou, recipient of the 2010 Presidential Medal of Freedom, who said she was always amazed when people came up to her and told her they were Christian. “I think, ‘Already?’” she said. “‘You already got it?’” “I’m working at it,” she continued, “which means that I try to be as kind and fair and generous and respectful and courteous to every human being.”1 She was in her eighties when she said that. It sounded like the perfect Christian baseline to me: how you treat every human being, neighbor and stranger alike. Even if you are still working at it, that is the mustard seed.

the idea of divine multiplicity is—the idea that one God can answer to more than one name and assume more than one form. Even if Christians will not go higher than three, the case is made: unity expresses itself in diversity. The One who comes to us in more than one way is free to surprise us in all kinds of ways.

I would like to tell you that it is the product of gaining wisdom, insight, and perspective through the study of other religions, but that would not be true. Instead, it is the product of losing my way, doubting my convictions, interrogating my religious language, and tossing many of my favorite accessories overboard when the air started leaking out of my theological life raft. Only then was I scared and disoriented enough to see something new when I looked back at my old landmarks, many of which I was approaching from an unfamiliar angle.

But if you stop and think about it, what better way could there be for me to actively pursue the God I did not make up—the one I cannot see—than to try for even twelve seconds to love these brothers and sisters whom I can see? What better way to shatter my custom-made divine mosaic than to accept that these fundamentally irritating and sometimes frightening people are also made in the image of God? Honest to goodness, with a gospel like that you could empty a church right out.

“Love God in the person standing right in front of you,” the Jesus of my understanding says, “or forget the whole thing, because if you cannot do that, then you are just going to keep making shit up.”

A disproportionate number of the famous Bible stories about Jesus involve religious strangers—Romans, Samaritans, Canaanites, Syrophoenicians—people who worshipped other gods or worshipped the same one he did in an unorthodox way. These were often the same people who blew Jesus’s mind, opening themselves up to what God could do in ways that escaped the people he knew best. When a centurion came seeking help for his servant, Jesus said he had never seen such faith. When a foreign woman came seeking help for her daughter, he praised her faith too. When a Samaritan returned to thank him for a

...more

The only clear line I draw these days is this: when my religion tries to come between me and my neighbor, I will choose my neighbor. That self-canceling feature of my religion is one of the things I like best about it. Jesus never commanded me to love my religion.

One of the ways the Son of Man smuggles himself into our midst is by showing up as a stranger in need of welcome. Welcome is the king’s solution to the problem of the stranger. Always has been, always will be.

neither the sheep nor the goats in Matthew’s parable knew which one they were. They were all on the sacred way of unknowing. The sheep were as surprised to learn they had done something right as the goats were to learn they had done something wrong. None of them had recognized the king in their midst. His clever disguises had fooled them all. The only thing that set them apart, in the end, was that half of them had made a habit of treating everyone they met with kindness and respect—even the ungrateful ones, even the ones that scared them—and that made all the difference.