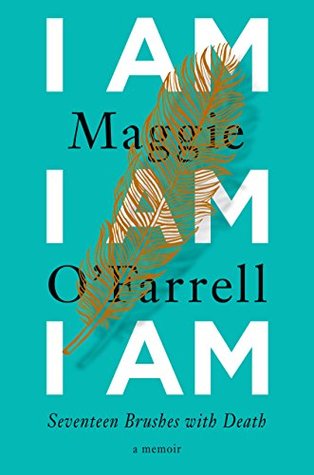

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

January 16 - February 20, 2022

If, as a child, you are struck or hit, you will never forget that sense of your own powerlessness and vulnerability, of how a situation can turn from benign to brutal in the blink of an eye, in the space of a breath. That sensibility will run in your veins, like an antibody. You learn fairly quickly to recognise the approach of these sudden acts against you: that particular pitch or vibration in the atmosphere. You develop antennae for violence and, in turn, you devise a repertoire of means to divert it.

There will be times, I tell them, when you’re teenagers and you’re out and someone will suggest something that you know is a bad idea and you will have to make a choice whether to join in or leave. To go with the group or against it. To speak up, to speak out, to say, no, I don’t think we should do that. No, I don’t want this. No, I’m going home.

It is more a desire to do something—anything—that pulls me out of the repetitive mundanity of a sixteen-year-old’s life. To differentiate this day from all the others in the endless chain of days I’m living through.

At sixteen, you can be so restless, so frustrated, so disgusted by everything that surrounds you that you are willing to leap off what is probably a fifteen-metre drop, in the dark, into a turning tide.

There is nothing unique or special in a near-death experience. They are not rare; everyone, I would venture, has had them, at one time or another, perhaps without even realising it.

We are, all of us, wandering about in a state of oblivion, borrowing our time, seizing our days, escaping our fates, slipping through loopholes, unaware of when the axe may fall.

If you are aware of these moments, they will alter you. You can try to forget them, to turn away from them, to shrug them off, but they will have infiltrated you, whether you like it or not. They will take up residence inside you and become part of who you are, like a heart stent or a pin that holds together a broken bone.

the thing is, I have this compulsion for freedom, for a state of liberation. It is an urge so strong, so all-encompassing that it overwhelms everything else. I cannot stand my life as it is. I cannot stand to be here, in this town, in this school. I have to get away. I have to work and work so that I can leave, and only then can I create a life that will be liveable for me.

infused with the awareness that I was always going to leave, that we both knew, on some level, that the urge had always been in me. I must, I now see, have driven her to distraction as a child: my intractability, my wildness, my irrational refusals, my craving for independence, my constant assertions of autonomy.

“If you have easy children there’s no justice in the world.”

We are cruising somewhere over the Pacific Ocean, at that vague halfway point in a long-haul flight when your grasp on time, on personal space, on hunger has dissolved and the hours are merging and collapsing together.

Crossing time zones in this way can bring upon you an unsettling, distorted clarity. Is it the altitude, the unaccustomed inactivity, the physical confinement, the lack of sleep, or a collision of all four?

That the things in life which don’t go to plan are usually more important, more formative, in the long run, than the things that do. You need to expect the unexpected, to embrace it. The best way, I am about to discover, is not always the easy way.

I tread the carpet along the rows of Fiction A–Z and think: I can read whatever I want. The realisation arrives like a gale, lashing past me, almost making me stagger.

The people who teach us something retain a particularly vivid place in our memories. I’d been a parent for about ten minutes when I met the man, but he taught me, with a small gesture, one of the most important things about the job: kindness, intuition, touch, and that sometimes you don’t even need words.

I have lived a great deal of my life near the sea: I feel its pull, its absence, if I don’t visit it at regular intervals, if I don’t walk beside it, immerse myself in it, breathe its air.

Karen Blixen wrote, in her Seven Gothic Tales, “I know a cure for everything: salt water…in one way or the other. Sweat, or tears, or the salt sea.”

Instead of an intimation of mortality, what is solidifying, taking root inside me, is something else, a welding together of this place with the sensation of a near-miss, an escape from something beyond my control.

What I thought I wanted was to be left in peace but what this really meant was that I was giving up: I was ready to die, to abandon the fight. It was easier than staying alive.

koan—a paradox or challenge that leads to enlightenment.

Occasionally, but not that often, I think about the person I was in my mid-twenties. I consider her. I try to recall how it felt to be that age.

Infidelity is as old as humanity: there is nothing about it you can think or say that hasn’t been thought or said before.

Arriving in Rome, age seventeen, was like receiving a blood transfusion.

I loved it all to the point of pain. I was dumbstruck, on the constant verge of tears, devastated by the idea that I would have to go home at the end of the week, and this place, these piazzas, these lives, would carry on without me. I wanted to see everything, go everywhere, never to return home.

When Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland was read to me and Alice sighs, “Oh, how I long to run away from normal days! I want to run wild with my imagination,” I remember rising up from my pillow and thinking, yes, yes, that’s it exactly.

After he had sailed around the Mediterranean in 1869, Mark Twain said that travel was “fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness.” Neuroscientists have been trying for years to pin down what it is about travel that alters us, how it effects mental change.

Neural pathways become ingrained, automatic, if they operate only by habit. They are highly attuned to alterations, to novelty. New sights, sounds, languages, tastes, smells stimulate different synapses in the brain, different message routes, different webs of connection, increasing our neuroplasticity. Our brains have evolved to notice differences in our environment: it’s how we’re alerted to predators, to potential danger. To be sensitive to change, then, is to ensure survival.

“Foreign experiences increase both cognitive flexibility and depth and integrativeness of thought, the ability to make deep connections between disparate forms.”*

I still crave the mental and physical jolt of being somewhere new, of descending aeroplane steps into a different climate, different faces, different languages.

I am desperate for change, endlessly seeking novelty, wherever I can find it.

I wanted to bring up my children to be travellers, to be curious about the world, to experience other cultures, other places, other sights.

When you are a child, no one tells you that you’re going to die. You have to work it out for yourself.

A teacher at school gave us John Donne’s Sonnet X to study, and the poet’s depiction of Death as an arrogant, ineffectual, conceited despot made me smile in recognition: Death, be not proud, though some have called thee Mighty and dreadful, for thou art not so… …nor yet canst thou kill me.

She is, she is, she is.

O’Farrell ends her memoir with an echo to the title: “She is, she is, she is.” Why does this phrase resonate with her?

SUGGESTED READING The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath Sir Gawain and the Green Knight; Giving Up the Ghost by Hilary Mantel Seven Gothic Tales by Isak Dinesen Lit by Mary Karr This Is the Story of a Happy Marriage by Ann Patchett Sex Object by Jessica Valenti A Field Guide to Getting Lost by Rebecca Solnit