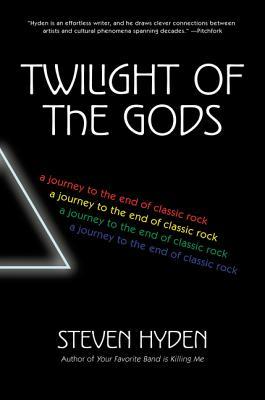

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Steven Hyden

Started reading

June 18, 2019

Our current world is a place where algorithms help us find an approximation of what we think we want. But the best albums deliver something you never knew you wanted. And it might take years of listening to the same record—over and over, because it hasn’t yet quite connected—before you finally get it.

Dylan songs are never about the destination. If you love Bob Dylan, you come to wish that the journey would never end, for this is what keeps his music fresh over so many listens.

What the narrator in that song goes through is an allegory for being a Dylan fan—if you never stop yearning, the song never ends.

But the real reason that Dylan at Newport matters in the context of our discussion of epochal concerts is because it established “don’t give the people what they want” as an artistic virtue in rock music.

But after Dylan, it suddenly became cool to do the opposite of what your audience might want at a live gig, because the opposite of what they want is what they might actually need.

How can I hold on to something that mortality is slowly stripping away from my grasp?

Conceptually, the “life on the road” song is supposed to present an authentic (i.e., depressing) depiction of rock stardom as a series of occupational hazards.

Part of loving classic rock is regarding the road as a fearsome yet romantic metaphor for living a life of absolute freedom outside of normal society—precisely the kind of life that most of us will never live.

Decadence will always be irresistible to young people, because decadence is sexy and fun, and also because doing what you want is the most visceral way to live. But once you’re older, and the buzz of sin wears off, the pursuit of being alive starts to matter more than the prizes you spend most of your life chasing.