More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

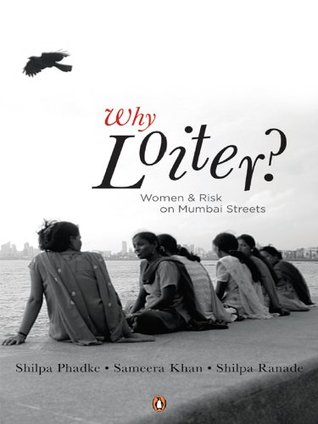

She loves the chaotic city of Mumbai and fantasizes that it will one day have a very large park.

We argue that there’s an unspoken assumption that a loitering woman is up to no good. She is either mad or bad or dangerous to society.

Of course, no one actually says this out loud. But every little girl is brought up to know that she must walk a straight line between home and school, home and office, home and her friend or relative’s home, from one ‘sheltered’ space to another.

This book maintains that all of us, whether we’re women or men, regardless of our differences...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

When society wants to keep a woman safe, it never chooses to make public spaces safe for her. Instead, it seeks to lock her up at home or at scho...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

The middle-class woman is then apparently privileged in every way other than gender.

that it is only by claiming the right to risk, that women can truly claim citizenship.

to see not sexual assault, but the denial of access to public space as the worst possible outcome for women.

Despite the pleasure we found in our travels, there was a sense that as women we did not have access to the full range of travelling pleasures.

We feel these limitations keenly as the ink begins to dry on our manuscript.

Feminism in India and elsewhere in the world has often been accused of a lack of joy—the terms of description our undergraduate participants in workshops used were inevitably negative—man-hating, anti-beauty, anti-family. While we disagree with these negative stereotypes, it is not untrue that even after decades of struggle, women cannot claim the right to fun.

Perhaps it is its history of social reform in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

But it also means that most areas of the city are busy late into the night, creating a sense of being occupied and crowded, which can be a source of comfort.

Mumbai’s women too do not have uncontested access to public space. They feel compelled to demonstrate at any given time that they have a legitimate reason to be where they are.

As every Bombay Girl knows, her freedom is subject to her knowing the ‘limits’, restrictions that often do not apply in quite the same way to her brothers.

For if this is the standard of access to public space in the country, then perhaps we lack both ambition and imagination.

Cities and definitions of citizenship have always been based on the principle of exclusion—on grounds of class, religion, race, age, sexual preference and property ownership, among others.

Unlike ancient city-states, in modern politically democratic countries, citizenship is theoretically premised on constitutional and legal equality. However, in practice, criteria that are not very different from those of ancient times are used to determine who are legitimate citizens with rights to the city.

In Mumbai today, the unbelongers are the poor, cast in the role of ungracious migrants who occupy the city’s spatial assets without officially recorded remuneration; the dalits and other lower castes whose presence is barely acknowledged, except grudgingly, when they take to the streets during Ambedkar Jayanti; and the Muslims, who are increasingly stereotyped as disagreeable outsiders, criminals and potential terrorists. Then there are the couples we don’t want sullying our park benches, the non-vegetarians we don’t want residing in our building complexes, the bhaiyas we don’t want selling

...more

This is buttressed by the increased reportage about public violence against women, which furthers the narrative that women are not safe in public spaces, sanctioning even greater restrictions on their movements.

The increased exclusion of marginal citizens is reflected in the increasing public violence against those seen to not belong. This violence takes the shape of ousting people from their homes and places of livelihood, of tolerating brutal acts committed by private agencies and the state against certain groups and communities, and generally ignoring the basic needs of entire sections of the city’s population.

the expressed concern for ‘women’s safety’ allows ever more brutal exclusions from public space in the guise of the righteous desire to protect women.

Prior to this, the working class had a greater claim to the city than they do now.

The blame for poverty can now be laid at the door of the individual, absolving the state of any responsibility. This simultaneously gives the middle and upper classes a sense of righteous claim to what are in reality common resources, such as water and space.

The greater an individual’s capacity to consume, the larger is ‘his’ claim to the city.

As anthropologist Arjun Appadurai (2000) puts it, ‘The rich in these cities seek to gate as much of their lives as possible, travelling from guarded homes to darkened cars to air-conditioned offices, moving always in an envelope of privilege through the heat of public poverty and the dust of dispossession.’

If the growing affinity towards neo-liberal economics has virtually legitimized violence towards the poorest of the poor, then the deepening of right-wing politics in the country, and indeed the city, has normalized the hatred towards Muslims.

‘Safety’ is the apparent reason why women are denied access to the public. The unarticulated reason why women are barred from public space is not just the fear that they will be violated, but also that they will form consenting relationships with ‘undesirable’ men.

This notion of safety encompasses not just sexual assault but also undesirable sexual liaisons even if they are consensual.

Women are then carefully monitored in an effort to not just prevent them from being assaulted but also to guard against their forming unsuitable alliances with men of their choice.

For women, decisions regarding their movements, partners, sexuality or even their own bodies are often not their choice.

This control of the movement of women is heightened in communities that perceive themselves as being marginalized. This is because women, traditionally seen as unsullied by the vagaries of the outside world, often become the symbolic markers of a community, the keepers of its tradition, and the bearers of its honour. Controlling them then becomes synonymous with the protection of the community.

The anxiety that marks Muslim women’s engagement with public space is then both the anxiety of being a woman in public, as well as the anxiety of being a woman of a particular minority community group in public. Thus, political and cultural safety as a Muslim is as much of a concern to them as the issue of everyday civic safety.

Safety for women is framed through the creation of a fallacious opposition between the middle-class respectable woman and the vagrant male (read: lower class, often unemployed, often lower caste or Muslim). By creating the image of certain men as the perpetrators of violence against women, women’s access to public space is further controlled and circumscribed and acquires an unquestionable rationality.

In an interesting sleight of hand, both the person perceived to be the potential molester and the potential victim of the act of molestation are denied legitimate access to public space on these grounds.

The elite by virtue of their wealth and the middle classes who define themselves as ‘honest tax-paying citizens’ feel most entitled to the city and its manifold resources and services.

In the apparent struggle between rampant economic and cultural globalization on the one hand and reactionary religious and cultural fundamentalism on the other, the profile of the desirable subject of the city is getting more narrowly defined every day.

Narratives of safety for women in the city then, tend to focus on a certain kind of woman.

Hence, even though public discussions of safety might appear to be about all women, they tend to focus implicitly only on middle-class women.

The middle-class woman is then apparently privileged in every way other than gender.

For women, respectability is fundamentally defined by the division between public and private spaces. Being respectable, for women, means demonstrating linkages to private space even when they are in public space.

Besides demonstrating that they belong in private spaces, women also have to indicate that their presence in public space is necessitated by a respectable and worthy purpose.

this purpose has to be visibly demonstrated to the effect that when any woman accesses public space, she has to overtly indicate her reason for being there.

When the tyranny of manufacturing purpose and producing an aura of privacy determines women’s access to public space, women who are inadequately able to demonstrate this privacy are seen to be the opposite of ‘private’ women, that is, ‘public women’ or ‘prostitutes’.

‘Respectable’ women could be potentially defiled in a public space while ‘non-respectable’ women are themselves a potential source of contamination to the ‘purity’ of public spaces and, therefore, the city.

Sex workers, perceived to be engaging in work that is inherently risky and non-respectable, are therefore seen to be outside the purview of protection available to other women.

Although statistics show that violence against women is far greater in private spaces such as homes,

Shame appears to attach to the victim of assault rather than to the perpetrator of the crime.

As foetuses, we are watched carefully for the presence of a penis and some of us never make it past that stage.

we are ogled at by men of all ages: uncles, neighbours and strangers alike. So much so, that we learn to watch ourselves and internalize society’s gaze, which tells us how we should conduct ourselves as good little women.