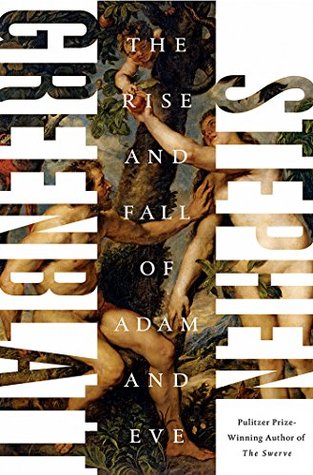

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Started reading

February 27, 2018

few years after he wrote the Confessions, Augustine managed to find in Adam’s eating of the forbidden fruit a whole litany of sins: pride, blasphemy, fornication, theft, avarice, even murder (“for he brought death upon himself”). What seemed like nothing turned out to be everything.

He had, of course, inherited the Genesis story, and with it St. Paul’s claim that Jesus had come to undo the catastrophic consequences of Adam’s disobedience.

Augustine was determined to save the divine creation from any imputation of injustice.

Adam would have died anyway, whether he had sinned or remained sinless. To die is not a punishment; it is part of what it means to be alive.

Fearing that treatises alone might not secure the condemnation of his doctrinal enemy, Augustine was careful to send, through an ally, a magnificent gift of eighty Numidian stallions to the papal court. Pelagius

was condemned, excommunicated, and exiled to Egypt.

Against Julian

No trace of this idea is found in the reported words of Jesus, nor does it exist as a significant theme in the vast body of rabbinical writing that flowed into the Midrash Rabbah and the Talmud or in the comparably vast Islamic tradition.

How would this have been possible, the Pelagians asked, if the bodies of Adam and Eve were substantially the same as our bodies?

Augustine’s obsessive engagement with the story of Adam and Eve spoke to something in his life.

Adam had fallen, Augustine wrote in the City of God, not because the serpent had deceived him.

He chose to sin because of pride—a “craving for undue exaltation”—and because he “could not bear to be severed from his only companion.