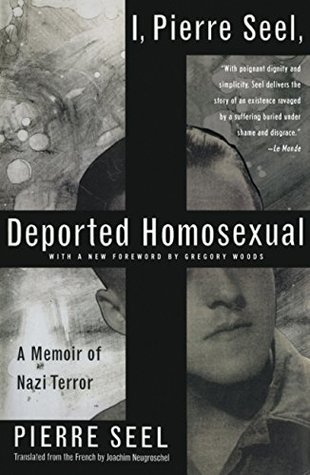

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Pierre Seel

Read between

February 6 - February 8, 2020

Nazi policies on homosexuality were, by definition, reactionary. They were vindictive and vengeful, an angry reaction to the perceived excesses of the period of the Weimar Republic, a visible solution to the problem of increased homosexual visibility.

The most sobering lesson to be learned from the Nazi abuse of homosexual men is that they did not need to formulate new laws under which to do so;

the men who had been imprisoned for homosexual crimes were treated as common criminals by the “liberators” and forced to serve out the full terms of their imprisonment.

At the end of the war Charles de Gaulle’s government extirpated most of the puppet Vichy regime’s laws—principally, of course, its various anti-Semitic edicts—but not its anti-homosexual laws, which would not be removed from the statute books until 1981.

A plaque and a sculpture (“hypocritically,” he says) are expected to perform the whole task of the commemoration of history.

Monuments tend to be rather demanding of those who encounter them: they announce emotion, but only rarely can they authentically evoke it.

A monument can, of course, be scanned in a complacent moment or captured in the click of a tourist’s camera, whereas a book takes a certain amount of time and effort to be appreciated.

In the Netherlands, the Homomonument Foundation was established in 1979,

The Gay Holocaust Memorial in Berlin was unveiled in May 2008.

My point is about the reversibility of our social advances even in those nations where we have made so much progress that we have allowed ourselves to take it for granted. The triumph of repressive National Socialism over all the experimental freedoms of the Weimar Republic tells us this. The vengeful triumphalism of homophobic responses to the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s in the United States and Western Europe tells us again.

Not until 2003 was Pierre Seel officially recognized as a Holocaust victim

in 2008 the municipality of Toulouse posthumously renamed a street in his honour (Rue Pierre Seel—Déporté français pour homosexualité—1923—2005).

I had entered the police station as a robbery victim, and I left as an ashamed homosexual.

Our Jewish friends were more nervous; whole Jewish families began leaving Alsace to escape the dangerous proximity of the Reich. A lot of Jews entrusted us with precious objects, which we buried in our cellar for the duration of the war.

But the illegal existence of a homosexual list remains an issue. In 1792, the Napoleonic Code had legalized homosexuality, and the burnings at the stake had ended even earlier. The Vichy government did not pass its anti-homosexual law until 1942.

I was not aware of the terrible fate that the Nazis had been inflicting on German homosexuals since 1933.

For though I signed the document as others did, to stop the agony, the bloodstains had made it illegible.

Sexual crime is an added burden for a prisoner’s identity.

A ghost has no fantasies,

I noted a few acquaintances (aside from the men who’d been in the police van on May 13, 1941). But it was hard to recognize them, for our clothes, our shaved heads, and our starved bodies had erased each man’s age and identity. He had become a staggering shadow of himself.

I was terrified whenever my name came booming out of the loudspeakers, for sometimes the authorities wanted to inflict monstrous experiments on me. Mostly these consisted of very painful injections in my nipples.

we soon recognized one of the things that they were forcing us to build: a crematorium. As our eyes took it in, horrified whispers accompanied our monstrous discovery.

Then the loudspeakers broadcast some noisy classical music while the SS stripped him naked and shoved a tin pail over his head. Next they sicced their ferocious German shepherds on him: the guard dogs first bit into his groin and thighs, then devoured him right in front of us. His shrieks of pain were distorted and amplified by the pail in which his head was trapped. My rigid body reeled, my eyes gaped at so much horror, tears poured down my cheeks, I fervently prayed that he would black out quickly.

I was eighteen, but I had no age.

I became a ghost in the service of death.

Another day, alas, I found myself, as I might have expected, facing a partisan at a turn in a precipitous road. We were too close to shoot. With the butt of his rifle, he smashed my jaw. But I didn’t lose consciousness; I managed to strike back. It was either him or me. The Nazis had taught us to kill, then forced us to kill. They had turned us into murderers.

I was not long in noting the quasi-total disappearance of homosexuals. I was unaware that ten years earlier all the night spots had been emptied of their habitués, all the organizations outlawed, and their thousands of members arrested by a special unit of the Gestapo. Those who had a record or were on a police list had been the first to be rounded up. The largest center of homosexual archives and associations, a brainchild of Magnus Hirschfeld, had been sacked long ago by the SA. Denunciations did the rest.

I was witnessing one of the Reich’s long-term programs: its goal was to put an end to marriage and family by creating a direct link between procreation and Nazism.

I was terrified by this quasi-animal breeding. Giving the Führer a son was a sacred, exciting mission: the propaganda had done its job.

Was I supposed to be convinced of the value of heterosexuality?

The whole time I was with the Soviet army, I don’t believe I was ever truly sober.

Liberation was only for others.

I returned as a ghost; I remained a ghost: it probably didn’t fully hit me that I was still alive.

Granted, Alsace was liberated and once again under French jurisdiction. But meanwhile the Pétain government, at Admiral Darlan’s behest, had adopted an anti-homosexual law, the first in 150 years—indeed, the first since the Old Regime. At the Liberation, de Gaulle’s government had implemented a highly approximate cleansing of the French penal code. But while the shameful anti-Semitic laws disappeared, the anti-homosexual law survived. It took pitched battles to wipe that law off the books forty years later, in 1981.

I had to bear witness, tell everything, demand restitution for my past, a past I shared with so many others, with people who had been buried and forgotten in Europe’s darkest hours. I had to bear witness in order to protect the future, bear witness in order to overcome the amnesia of my contemporaries.

I now decided to begin a series of steps to have the government recognize my deportation and thereby the Nazi deportation of other homosexuals.

The reality of what had occurred in that place was hypocritically transformed into a symbolic plaque and sculpture; yet we are still haunted by the memory of that closed space.

As for the overall deportations of homosexuals, that fact is still vigorously contested:

In 1989 serious incidents occurred in many cities at this commemoration of all victims of the Nazi barbarism. In Besançon, some of the people watching the ceremony shouted: “Throw the fags into the ovens! They ought to start the ovens again and put them in!” The wreath for the homosexual deportees was trampled, which aroused the indignation of many people. In Paris, at the tip of the Ile de la Cite, a deportation monument has been put up at the apse of the Cathedral of Notre-Dame; at the request of the Reverend Father Riquet, a fence was placed around it to keep out undesirable tributes. The

...more

This administrative demand, a legal requirement, is straight out of a Kafka novel.

When I am overcome with rage, I take my hat and coat and defiantly walk the streets. I picture myself strolling through cemeteries that do not exist, the resting places of all the dead who barely ruffle the consciences of the living. And I feel like screaming. When will I succeed in having my deportation recognized? When will I succeed in having the overall Nazi deportation of homosexuals recognized? In my apartment house and throughout my neighborhood, many people greet me, politely listen to my news, and inquire about the progress of my case. I’m grateful to them and I appreciate their

...more