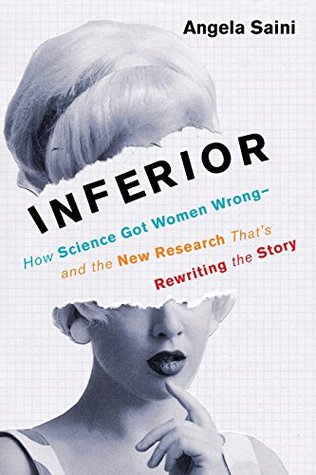

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Angela Saini

Read between

May 21 - May 25, 2023

If you were the geek growing up, you’ll recognize how lonely it can be. If you were the female geek, you’ll know it’s far lonelier. By the time I reached my final years of school, I was the only girl in my chemistry class of eight students. I was the only girl in my mathematics class of about a dozen. And when I decided to study engineering at university, I found myself the only woman in a class of nine.

I was often the only student who wasn't a cis man in physics classes beyond intro. This is a big nerd mood for all trans nerds and all girl nerds. I felt like I was betraying girls by not being a female nerd role model. Nerd trans women have to contend with a boys' club nerd culture AND with people who use their nerd status to deny their womanhood.

A couple of years after I graduated from university, in January 2005, the president of Harvard University, economist Lawrence Summers, gave voice to one controversial explanation for this gap. At a private conference he suggested that “the unfortunate truth” behind why there are so few top women scientists at elite universities might in some part have to do with “issues of intrinsic aptitude,” that a biological difference exists between women and men. A few academics defended him but, by and large, Summers was met by public outrage. Within a year he announced his resignation as president.

Even today, we live in the balance of that question, feeding our babies fantasies in pink and blue with the assumption they are deeply different. We buy trucks for our boys and dolls for our girls, and delight when they love them. These early divisions reflect our belief that there’s a string of biological differences between the sexes, which perhaps shape us for different roles in society. Our relationships are guided by the notion, fed by many decades of scientific research, that men are more promiscuous and women are monogamous. Even our visions of the past are loaded with these myths. When

...more

Many believe that what science says shouldn’t make a dent in the battle for basic rights. We deserve an equal playing field, they say, and they’re right. But whether or not it sits easily with us, we can’t ignore biology either. If biological differences exist, we can’t help but want to know. More than that, if we want to build a fairer society, we need to be able to understand these gaps and accommodate them.

Women are so grossly underrepresented in modern science because, for most of history, they were treated as intellectual inferiors and deliberately excluded from it. It should come as no surprise, then, that this same scientific establishment has also painted a distorted picture of the female sex. This, in turn again, has skewed how science looks and what it says even now.

This is best explained by the perennial problem of child care, which lifts women out of their jobs at precisely the moment their male colleagues are putting in more hours and being promoted. When researchers Mary Ann Mason, Nicholas Wolfinger, and Marc Goulden published a book on this subject in 2013, titled Do Babies Matter: Gender and Family in the Ivory Tower, they found that married mothers of young children in the United States were a third less likely to receive tenure-track jobs than married fathers of young children.

Gender bias is so steeped in the culture, their results implied, that women were themselves discriminating against other women.

So here, in all the statistics on housework, pregnancy, child care, gender bias, and harassment, we have some explanations for why so few women are at the top in science and engineering. Rather than falling into Lawrence Summers’s tantalizing trap of assuming the world looks this way because it’s the natural order of things, take a step back. Imbalance in the sciences is at least partly because women face a web of pressures throughout their lives, which men often don’t face.

Iran, similarly, has high proportions of female scientists and engineers. Mathematician Maryam Mirzakhani, the only woman to have won the prestigious Fields medal, was born in Tehran. If women were less capable of doing science than men, we wouldn’t see these variations, proving again that the story is more complicated than it appears.

Things got worse before they got better. In its early days, when science was a pastime for enthusiastic amateurs, women had at least some access to it—even if this was only by marrying wealthy scientists and having the chance to work with them in their laboratories. By the end of the nineteenth century, science had transformed into something more serious, with its own set of rules and official bodies. By then, women found themselves almost completely pushed out, says Miami University historian Kimberly Hamlin. “The sexism of science coincided with the professionalization of science. Women

...more

It was thought that merely having women around might disrupt the serious intellectual work of men, she adds. The celibate male tradition of medieval Christian monasteries continued at the universities of Oxford and Cambridge until late into the nineteenth century. Professors weren’t allowed to marry. Cambridge would wait until 1921 to award degrees to women. Similarly, Harvard Medical School refused to admit women until 1945. The first woman applied for a place almost a century earlier.

When mathematician Emmy Noether was put forward for a faculty position at the University of Göttingen during the First World War, one professor complained, “What will our soldiers think when they return to the university and find that they are required to learn at the feet of a woman?” Noether lectured unofficially for the next four years under a male colleague’s name and without pay. Albert Einstein described her in the New York Times after her death as “the most significant creative mathematical genius thus far produced since the higher education of women began.”

And as recently as 1974 the Nobel Prize for the discovery of pulsars wasn’t given to astrophysicist Jocelyn Bell Burnell, who actually made the breakthrough, but to her male supervisor.

There are also those who insist that men played the dominant part in human evolutionary history because they hunted animals, while women had the apparently less challenging role of staying at home and caring for children. They’ve argued that males are responsible for humans evolving high intelligence and creativity. Still others say that women experience menopause because men don’t find older women attractive.

Decades of rigorous testing of girls and boys confirm that there are few psychological differences between the sexes, and that the differences seen are heavily shaped by culture, not biology. Research into our evolutionary past shows that sexual division of labor and male domination are not biologically hardwired into human society, as some have claimed, but that we were once an egalitarian species. Even the age-old myth about women being less promiscuous than men is being overturned.

“Where are all the women scientists? Where are the women Nobel Prize winners?” he asked, sneering. “Women just aren’t as good at science as men are. They’ve been shown to be less intelligent.” He walked up so close to my face that I was literally backed into a corner. What was a sexist rant quickly became racist, too. I tried to argue back. I listed the accomplished female scientists I knew. I hastily marshaled a few statistics about school-age girls being better at mathematics. But in the end, I gave up. There was nothing I could say for him to think of me as his equal.

This sounds absolutely terrifying to experience. This man literally cornered her and invaded her personal space, deliberately as a dominance posture

We can guess how Caroline Kennard must have felt about Darwin’s comments from the fiery, long response she sent back. Her second letter is not nearly as neat as her first. She argues that, far from being housebound, women contribute just as much to society as men do. It was, after all, only in wealthier middle-class circles that women tended not to work. For many Victorians, women’s incomes were vital to keeping families afloat. The difference between men and women wasn’t the amount of work they did, but the kind of work they were allowed to do. In the nineteenth century, women were barred

...more

Another example is Darwin’s cousin, the English scientist Francis Galton, remembered by history as the father of eugenics and for his devotion to measuring the differences between people. Among his quirkier projects was a “beauty map” of Britain, produced near the end of the nineteenth century by secretly watching local women and grading them from the ugliest to the most attractive.

“It meant a way to be modern,” says historian Kimberly Hamlin, whose 2014 book From Eve to Evolution: Darwin, Science, and Women’s Rights in Gilded Age America charts women’s responses to Darwin. Evolution was an alternative to religious stories that painted woman as man’s spare rib. Christian models for female behavior and virtue were challenged. “Darwin created a space where women could say that maybe the Garden of Eden didn’t happen. . .and this was huge. You cannot overestimate how important Adam and Eve were in terms of constraining and shaping people’s ideas about women.”

Her criticisms were passionately laid out in a book she published in 1894 called The Evolution of Woman, an Inquiry into the Dogma of Her Inferiority to Man. “It was shocking,” says Hamlin. Marshalling history, statistics, and science, this was Gamble’s piercing counterargument to Darwin and other evolutionary biologists. She angrily tweezed out their inconsistencies and double standards.

In evolutionary terms, drawing assumptions about women’s abilities from the way they happened to be treated by society at that moment was narrow-minded and dangerous.

In 1893 New Zealand became the first self-governing country to grant women the vote. The battle would take until 1918 in Britain, although only for women over the age of thirty.

But Wolfe immediately saw the danger in scientists like him overstepping their expertise. “It is a fine illustration of the sort of mental pathology a scientist, especially a biologist, can exhibit when, with slight acquaintance with other fields than his own, he ventures to dictate from ‘natural law’ (with which Mr Heape claims to be in most intimate acquaintance) what social and ethical relation shall be,” Wolfe mocked in his review. “He sees only disaster and perversion in the modern woman movement.”

In 1891 another unusual experiment, this time in France by university professor Charles-Édouard Brown-Séquard, finally began to get to the root of the mystery. He suspected that male testes might contain some unknown substance that influenced masculinity. He proved his hypothesis the hard and fast way, by repeatedly injecting himself with a concoction made out of the blood, semen, and juices from the crushed testicles of guinea pigs and dogs. He claimed (although his findings were never replicated) that this cocktail increased his strength, stamina, and mental clarity.

Sex hormones play a crucial role in determining how male or female a person looks even before birth. In the womb, it’s interesting to note, all fetuses start out physically female. “The default blueprint is female,” says Richard Quinton, consultant endocrinologist at hospitals in Newcastleupon-Tyne in northeast England.

The same research was done on women using estrogen. Another article in the Lancet in 1931, the researcher Jane Katherine Seymour has noted, connected the female hormones to femininity and childbearing. Under their effect, it also said, women “would tend to develop a more passive and emotional, and less rational, attitude towards life.”

Lingering stereotypes about sex hormones remain. But they are being constantly challenged by new evidence. According to endocrinologist Richard Quinton, common assumptions about testosterone have already been shown to be way off the mark. Women with slightly higher than usual levels of testosterone, he says, “don’t actually feel or appear any less feminine.”

Gender, meanwhile, is a social identity, influenced not only by biology but also by external factors such as upbringing, culture, and the effect of stereotypes. It’s defined by what the world tells us is masculine or feminine, and this makes it potentially fluid. For many people their biological sex and their gender aren’t the same.

In 1994 the Indian government outlawed sex selection tests, but unscrupulous independent clinics and doctors still offer them for a fee, in private and under the radar. Khurana never wanted to have one of these prenatal scans, she tells me. In the end, she wasn’t given the choice. During her pregnancy, she claims she was tricked into eating some cake that contained egg, to which she’s allergic. Her husband, a doctor, then took her to a hospital, where a gynecologist advised her to have a kidney scan under sedation. It was then, she believes, he deliberately found out the sex of her babies

...more

Another reason is that women’s immune systems are so powerful that they can sometimes backfire. “You start regarding yourself as foreign and your immune system starts attacking its own cells,” explains Kathryn Sandberg.

Women also tend to get more painful joint and muscle diseases in general, observes Austad. Part of this is due to autoimmune diseases that affect the joints, such as arthritis.

The results have indeed shown a link between the number of X chromosomes a mouse has and its health. Arnold describes “three dramatic cases.” When he and his team looked at body weight, they found that mice get fat if their gonads are removed. But animals with two X chromosomes get a lot fatter than those with just one.

The debate about just how deep the dividing line is between women and men continues to rage inside the scientific community. It has been fueled most recently by anger over exactly the opposite problem: the habit of medical researchers to leave women out of tests for new drugs, because their bodies were thought to be so similar to men’s.

Another problem is that women may respond differently from men to certain drugs. Medical researchers in the mid-twentieth century often assumed this couldn’t be a problem. “There was a notion that women were more like little men,. . .that if this treatment works in men, it will work on women,” says Janine Clayton, director of the Office of Research on Women’s Health at the NIH in Washington, DC, which funds the vast majority of US health research.

“So heart attacks, for example, have different symptoms. Our research has shown that women who are going to have a myocardial infarction [heart attack] are more likely to have symptoms like insomnia, increasing fatigue, pain anywhere in the head all the way down to the chest, the weeks before they have a heart attack. Whereas men are less likely to have those symptoms and are more likely to present with the classic crushing chest pain.”

And Ambien is among the most popular. Its side effects, however, include severe allergic reactions, memory loss, and the possibility of it becoming habit forming. The effects of zolpidem can also last longer than one night, leading to drowsiness the following day, which can in some cases make it dangerous to drive. Long after it was approved for market, research emerged that women given the same dose as men were more likely to suffer morning drowsiness. Eight hours after taking zolpidem, 15 percent of women but only 3 percent of men had enough of the drug in their system to raise their risk of

...more

Once we start to assume that women have fundamentally different bodies from men, this quickly raises the question of how far the gaps stretch. Do sex chromosomes affect not just our health but all aspects of our bodies and minds, for example? If every cell is affected by sex, does that include brain cells? Do estrogen and progesterone not just prepare a woman for pregnancy and boost her immunity but also creep into her brain, affecting how she thinks and behaves? And does this mean that gender stereotypes, such as baby girls preferring dolls and the color pink, are in fact rooted in biology?

Girls and boys, in short, would play harmlessly together, if the distinction of sex was not inculcated long before nature makes any difference. —Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, 1792

We know that around the age of two or three, children start to become aware of their own sex. Between the ages of four and six, a boy will realize that he will grow up to be a man and a girl that she will be a woman. It’s also by then that children have some understanding of what’s appropriate for each gender according to the culture they’re in.

When the then president of Harvard University, Lawrence Summers, controversially suggested in 2005 that the shortfall of female scientists and mathematicians might be because of innate biological differences between women and men, Simon Baron-Cohen used this study to defend him. Harvard University cognitive scientist Steven Pinker and London School of Economics philosopher Helena Cronin have both deployed it to argue that innate differences between the sexes exist. It has even made it into a Bibleinspired self-help book, His Brain, Her Brain, about how “divinely designed differences” between

...more

Like many senior scientists do, Baron-Cohen left the experiment itself to a junior colleague, who had just joined his team. Jennifer Connellan was a twenty-two-year-old American postgraduate student. “I can’t believe he accepted me into his lab actually,” she tells me. By her own admission, she was young and inexperienced.

Simon Baron-Cohen was always aware that he was wading into divisive territory. He writes near the start of The Essential Difference that he delayed finishing it for years because he thought the topic was too politically sensitive. He makes the defense often made by scientists when they’re publishing work that might be interpreted as sexist—that science shouldn’t shy away from the truth, however uncomfortable it is. It’s a claim that runs all the way through work by people who claim to see sex differences. Objective research, they say, is objective research.

According to Hines, this isn’t what we see. Tallying all the scientific data she has seen across all ages, Hines believes that the “sex difference in empathizing and systemizing is about half a standard deviation.” This would be equivalent to a gap of about an inch between the average heights of men and women. It’s small. “That’s typical,” she adds. “Most sex differences are in that range, And for a lot of things, we don’t show any sex differences.”

Hines repeated this exercise using more recent research. She found that only the tiniest gaps, if any, existed between boys’ and girls’ fine motor skills, ability to perform mental rotations, spatial visualization, mathematics ability, verbal fluency, and vocabulary. On all these measures, boys and girls performed almost the same.

In every case, except for throwing distance and vertical jumping, females are less than one standard deviation apart from males. On many measures, they are less than a tenth of a standard deviation apart, which is indistinguishable in everyday life.

“Even though on the average there is no sex difference in IQ, I think still boys get encouraged at the top. I think in some social environments, they don’t get encouraged at all, but I think in affluent, educated social environments, there is still a tendency to expect more from boys, to invest more in boys,” she tells me.

The skepticism came to a head in 2007 when New York psychologists Alison Nash and Giordana Grossi dissected the experiment in forensic detail and catalogued a string of problems, big and small. For one thing, the paper’s grand claim that the experiment’s conclusions were “beyond reasonable doubt” seemed an uncomfortable stretch when, in fact, not even half the boys in the study preferred to stare at the mobile and an even smaller percentage of the girls preferred to stare at the face. But their most damning criticism was that Connellan knew the sex of at least some of the babies she was

...more

When I ask Simon Baron-Cohen to give me his own thoughts on the experiment, he tells me by e-mail, “It was designed thoroughly and was scrutinised through peer review and as such it met the bar for good science. No study is above criticism in the sense that one can always think of ways to improve the study, and I hope when a replication is attempted, it will also be improved.”