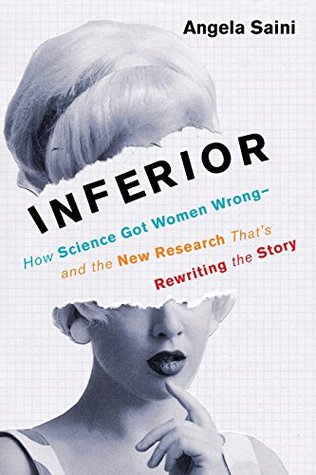

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Angela Saini

Read between

January 27 - March 28, 2018

We believe that what science offers us is a story free from prejudice.

A couple of years after I graduated from university, in January 2005, the president of Harvard University, economist Lawrence Summers, gave voice to one controversial explanation for this gap. At a private conference he suggested that “the unfortunate truth” behind why there are so few top women scientists at elite universities might in some part have to do with “issues of intrinsic aptitude,” that a biological difference exists between women and men.

Women are so grossly underrepresented in modern science because, for most of history, they were treated as intellectual inferiors and deliberately excluded from it. It should come as no surprise, then, that this same scientific establishment has also painted a distorted picture of the female sex. This, in turn again, has skewed how science looks and what it says even now.

Kelly Lynn Thomas liked this

The common trend is for women to be around in high numbers at the undergraduate level but to thin out as they move up the ranks. This is best explained by the perennial problem of child care, which lifts women out of their jobs at precisely the moment their male colleagues are putting in more hours and being promoted.

Women now make up almost half the labor force, yet in 2014 the bureau found that women spent about half an hour more every day than men doing household work.

In households with children under the age of six, men spent less than half as much time as women taking physical care of these children.

Housework and motherhood aren’t the only things affecting gender balance. There’s outright sexism, too.

female and male faculty were equally likely to exhibit bias against the female student.” Gender bias is so steeped in the culture, their results implied, that women were themselves discriminating against other women.

“The sexism of science coincided with the professionalization of science. Women increasingly had less and less access,” she explains.

Rosalind Franklin’s enormous part in decoding the structure of DNA was all but ignored when James Watson, Francis Crick, and Maurice Wilkins shared the Nobel after her death in 1962.

Having more women in science is already changing how science is done. Questions are being asked that were never asked before. Assumptions are being challenged. Old ideas are giving way to new ones. The distorted, often negative picture that research has painted of women in the past has been powerfully challenged in recent decades

Decades of rigorous testing of girls and boys confirm that there are few psychological differences between the sexes, and that the differences seen are heavily shaped by culture, not biology.

As anthropologist Kristen Hawkes at the University of Utah put it to me when I interviewed her about her work on menopause for the final chapter of this book, “If you’re really paying attention to biology, how can you not be a feminist? If you’re a serious feminist and want to understand what the underpinnings of these things are, and where they come from, then biology—more science, not less science.”

“Let the ‘environment’ of women be similar to that of men and with his opportunities, before she be fairly judged, intellectually his inferior, please.”

When these prejudices met evolutionary biology, they turned out to be a particularly toxic mix, one that would poison scientific research for many decades.

Gamble believed there was more to the cause than securing legal equality. One of the biggest sticking points in the fight for women’s rights, she recognized, was that society had come to believe women were built to be lesser than men.

In evolutionary terms, drawing assumptions about women’s abilities from the way they happened to be treated by society at that moment was narrow-minded and dangerous. Women had been systematically suppressed over the course of human history by men and their power structures,

In the early days of endocrinology, assumptions about what it meant to be masculine or feminine came from the Victorians.

It took a while for scientists to accept the truth: that all these hormones really did work together in both sexes, in synergy.

A radical move from the old Victorian orthodoxies of the kind Charles Darwin had subscribed to was underway. People could no longer clearly define the sexes anymore. There was overlap. Femaleness and maleness, femininity and masculinity, were turning into fluid descriptions, which might be as much shaped by nurture as by nature.

The facts, as they emerge, are important. In a world in which so many women continue to suffer sexism, inequality, and violence, they are capable of turning old stereotypes on their head. They can transform the way we see each other. With good research and reliable data, the strong can become weak and the weak, strong.

When it comes to the most basic instinct of all—survival—women’s bodies tend to be better equipped than men’s. The difference exists from the moment a child is born.

“If you have parity in your survival rates, it means you aren’t looking after girls,” says Lawn. “The biological risk is against the boy, but the social risk is against the girl.”

“If you look across all the different types of infections, women have a more robust immune response.” It isn’t that women don’t get sick. They do. They just don’t die from these sicknesses as easily or as quickly as men do.

while women are generally hit by fewer viruses during an infection, they tend to suffer more severe flu symptoms than men do. She reasons that this may be because women’s immune systems mount sturdier counterattacks to viruses, but then suffer when the effects of these counterattacks upset their own bodies.

It’s difficult to tear apart the effects of biology from other effects. Society and the environment can sometimes affect illness more than a person’s underlying biology.

admitting that period pain hasn’t been given the attention it deserves, partly because men don’t suffer from it.

Having just one copy of the genes, only on the X chromosome, can have repercussions for a man’s body. “It’s long been thought, and there is good evidence for this, that having two versions of the gene buffers women against certain diseases or environmental changes,”

When it comes to the basic machinery of our bodies, scientists have often assumed that studying one sex is as good as studying the other.

“Although there were some reasons to avoid doing experiments on women, it had the unwanted effect of producing much more information about how to treat men than women,”

“It’s certainly a real possibility that the reason there are more adverse events in women than in men is because the whole process of drug discovery is tremendously biased towards the male,”

Is the only alternative to women being thought of as “little men” to have them treated as an entirely different kind of patient? As more detailed research is done, it’s becoming clear that seeing some variation between women and men when it comes to health and survival doesn’t mean we should ditch the notion that our bodies are in fact similar in many ways, too.

“Both sex and gender are important factors for health,” reminds Janine Clayton. Ideally, then, people should be treated according to the spectrum of factors that set them apart. Not just sex, but also social difference, culture, income, age, and others. As Sarah Richardson has written, “A female rat—not to mention a cell line—is not an embodied woman living in a richly textured social world.”

Medical dosages might be affected by a better understanding of how a woman’s body responds across her menstrual cycle.

In 1993 the US Congress introduced the National Institutes of Health Revitalization Act, which includes a general requirement for all NIH-funded clinical studies to include women as test subjects, unless they have a good reason not to. By 2014, according to a report in Nature by Janine Clayton, just over half of clinical-research participants funded by the NIH were women.

As yet, no one has been able to fully explain how, at the very start of a child’s life, its brain gets set on a path toward being more male or more female.

One commentator compared talking about fetal testosterone and sex differences in the brain to talking about race and gaps in intelligence.

Critics pointed out, for instance, the bias in language being used to describe masculinity and femininity. Anything tomboyish, for instance, was interpreted as a girl behaving like a boy. But who was to say that this wasn’t in fact a normal, common feature of being female?

In 2010, Hines repeated this exercise using more recent research. She found that only the tiniest gaps, if any, existed between boys’ and girls’ fine motor skills, ability to perform mental rotations, spatial visualization, mathematics ability, verbal fluency, and vocabulary. On all these measures, boys and girls performed almost the same.

when it comes to children raised under normal conditions, without unusual medical conditions, large gaps between girls and boys haven’t been found. “It’s quite rare to find differences in typical development.”

In every case, except for throwing distance and vertical jumping, females are less than one standard deviation apart from males. On many measures, they are less than a tenth of a standard deviation apart, which is indistinguishable in everyday life.

When it comes to intelligence, too, it has been convincingly established that there are no differences between the average woman and man.

The need to avoid this sort of problem is exactly why scientists are advised to carry out these studies blind, without knowing the sex of their subjects. Without this safety measure, it’s hard to take the results seriously.

Connecting testosterone levels before birth to behavioral sex differences later on, she says, “is just this huge explanatory leap, and it leaves me uncomfortable because I don’t think it’s much of a scientific explanation when you make such a big leap.

Men and women may be different, but only in the same way that every individual is from the next. Or, as she has also put it, “that gender differences fall on a continuum, not into two separate buckets.”

The scientific picture emerging now is that there may be very small biological differences, but that these can be so easily reinforced by society that they appear much bigger as a child grows.

Fausto-Sterling believes that every individual should be thought of as a developmental system—a unique and ever-changing product of upbringing, culture, history, and experience, as well as biology.

Hormonal effects on the brain or other deep-seated biological gaps aren’t necessarily the most powerful reason for the gaps we see between the sexes. Culture and upbringing could better explain why boys and girls grow up to seem different from each other.

Understand that bodies are shaped by culture from the very get-go,” explains Fausto-Sterling. “If you neglect a child at birth, their brain stops developing and they’re pretty messed up. If you highly stimulate a child, if they’re within a normal developmental range, they now develop all sorts of capacities you didn’t know they had or didn’t have the potential to develop. So the question always goes back to how development works.”

“Of course the male brain looks more like the female brain than either of them look like the brain of another species,” Ruben Gur admits. But this similarity aside, he’s nevertheless convinced that women’s brains are different in a host of other ways, and that this in turn reveals something about how women think and behave.